Makhnovshchina Anarchists - 1917-21

There seems to be in the character of the people of eastern Europe a positive zest in destruction, summarized in the word "pogrom," which means literally a smashing. The anarchical element is Russian, Eastern, and entirely spontaneous, a tendency always latent in the unschooled Russian soul. The revolts which are recorded in Russian history, before the advent of Socialism, were always of this "smashing," unconstructive type. Such were the Cossack risings under Stenka Rasin in the seventeenth and under Pugatchev in the eighteenth century. The latter aimed at creating a "peasant empire," and wherever he marched he liberated the serfs in field, factory, and mine, slaughtered the landlords and divided their estates. That was in 1773, but the memory of his immense massacres and burnings remains, and the peasants of the Urals and Volga preserve the legend of his two years' rebellion. The various semi-brigand leaders who sprang up recently in southern Russia, and especially in the Ukraine, continued this primitive, native Russian tradition of revolt.

There seems to be in the character of the people of eastern Europe a positive zest in destruction, summarized in the word "pogrom," which means literally a smashing. The anarchical element is Russian, Eastern, and entirely spontaneous, a tendency always latent in the unschooled Russian soul. The revolts which are recorded in Russian history, before the advent of Socialism, were always of this "smashing," unconstructive type. Such were the Cossack risings under Stenka Rasin in the seventeenth and under Pugatchev in the eighteenth century. The latter aimed at creating a "peasant empire," and wherever he marched he liberated the serfs in field, factory, and mine, slaughtered the landlords and divided their estates. That was in 1773, but the memory of his immense massacres and burnings remains, and the peasants of the Urals and Volga preserve the legend of his two years' rebellion. The various semi-brigand leaders who sprang up recently in southern Russia, and especially in the Ukraine, continued this primitive, native Russian tradition of revolt.

Anarchism for a long time enjoyed the complimentary reputation of being the most irreconcilable enemy of bourgeois society. Anarchism was a mixture of a great number of entirely heterogeneous elements - individualism with its metaphysical postulate of absolute freedom and complete sovereignty of the individual, primitive communism based on the belief in the inherent goodness and generosity of human nature, and proletarian protest against the opportunist, possibilist and bourgeois reformist character of the Socialist parties. The new style Anarchists in Russia, who discarded Anarchy as a mere ideal of the far distant future, and in the face of the allied intervention and civil war, endeavored to destroy the "State", i.e., the Soviet Government, and establish Anarchism. Irreconcilable enemies of every government, they incited the hungry workers of the cities against the Soviet Government because it did not give them enough food, and when the Government through requisitions from the villages endeavored to obtain food, they incited the peasants to revolt against a government that was "robbing them of their grain".

The dissatisfaction of the peasants with the requisitioning policy of the government (owing to the blockade, the intervention, and the ensuing disorganization of industry, the government was unable to provide the peasants with the necessary manufactured articles) gave the Anarchists of the new style, who were so incessantly raving against the dictatorship, against the Red Army, etc., a chance to put into effect their own theories of government, or rather non-government.

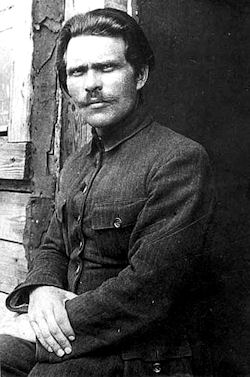

Among the partisan leaders which the disorders or revolution and civil war produced in Eastern Europe was the Ukrainian peasant chieftain, Nestor Ivanovich Makhno. Makhno, the anarchist partisan leader, was among the most colorful and heroic figures of the Russian Revolution and Civil War. His movement in the Ukraine represents one of the few occasions in history when anarchists controlled a large territory for an extended period of time. For more than a year he was a greater power on the steppe than either Trotsky or Denikin.

Among the partisan leaders which the disorders or revolution and civil war produced in Eastern Europe was the Ukrainian peasant chieftain, Nestor Ivanovich Makhno. Makhno, the anarchist partisan leader, was among the most colorful and heroic figures of the Russian Revolution and Civil War. His movement in the Ukraine represents one of the few occasions in history when anarchists controlled a large territory for an extended period of time. For more than a year he was a greater power on the steppe than either Trotsky or Denikin.

Makhno was an intellectual, a former village schoolmaster once imprisoned for a political offence, a clever and energetic man. Makhno was a comparatively young man, who from his childhood was said to have lived by thieving, and at the age of twenty was condemned to hard labor for life for robbery and many murders. Makhno became an anarchist as the result of nine years of imprisonment, following his arrest on account of his political views when he was a student eighteen years old.

Makhno, the insurgent leader of the Ukraine, was nearly unknown outside of Russia, but as a phenomenon inside Russia among the peasants, a knowledge of him and his doings is essential to an understanding of the peasants' state of mind, or the possibility of peasant action in the future. Makhno was a strange fellow, about whom, as about Napoleon in his lifetime, a cycle of legends has formed. He was only five feet tall, but with the shoulders of Ajax and the arms of a gorilla.

The few facts that were definitely established concerning Makhno are that he was born in the Ukraine near Gulaipol, where he later became a schoolmaster; that he had little education, but a great quantity of shrewd common sense and a very keen intuitive sense of peasant psychology; that he was intensely opposed to the rich, and devoted himself entirely to the interests of the peasants; that he was opposed, alike, to the Bolsheviki and all the anti-Bolshevist forces that had so far arisen; and that, although he himself was no great military leader, he headed a greater number of the insurgent bands which covered Ukraine, with which he operated very successfully, and continuously, without any support other than that of his peasant followers.

At the time of the first revolution in Russia in 1917, he was amnestied, and returned to his native village and organized a small anarchist party among his fellow villagers. He immediately resumed his old trade, haying gathered round him a gang of common criminals who called themselves anarchists.

It appears he started out by gathering together a small group of peasants with whom he began operations by pillaging various sugar and flour mills in the Ukraine. His success produced imitators, many of whom thrived for a time, but he alone survived.

In the early stages of his career, his most serious rival was Gregorieff, the leader of a similar partisan band with about the same number of followers. According to all accounts, he invited Gregorieff to a conference, promptly picked a quarrel with him, shot him dead, made a short and trenchant speech to Gregorieff's men, and as promptly attached them to himself.

During the first phase of the Russian Revolution he was a member of the Yelisavetgrad Executive Committee of the labor deputies. At the time of the German occupation he became a popular personality in the Government of Yekaterinoslav, where he prepared the uprising against the German rule. When the Germans invaded the Ukraine, he took refuge with his followers in a neighboring forest, where his forces soon grew, and he conducted successful guerrilla warfare against the invaders. Makhno was regarded by the village population as one of those "holy fighters" for the cause of the village who put an end to a regime which attempted to carry everything away from the Ukraine and to establish a terroristic rule upon the flat country.

The so-called Makhnovshchina or "Green Army" carried the Black Flag. In Ukraine the Anarchist partisan leader Makhno for certain periods held large tracts of territory. Makhno, covered with glory as he was, constantly tried to utilize his popularity among the peasants of the Yekaterinoslav and neighboring governments for an independent policy. He called himself an anarchist, but denied all connection with the party - he wanted to be more anarchistic than the anarchists. In general his politics in relation to his own followers as well as the peasants in the neighborhood was characterized by the attempt to distribute among them, especially among the poorest, the property, mainly Jewish, which had been plundered and collected in the small towns.

The so-called Makhnovshchina or "Green Army" carried the Black Flag. In Ukraine the Anarchist partisan leader Makhno for certain periods held large tracts of territory. Makhno, covered with glory as he was, constantly tried to utilize his popularity among the peasants of the Yekaterinoslav and neighboring governments for an independent policy. He called himself an anarchist, but denied all connection with the party - he wanted to be more anarchistic than the anarchists. In general his politics in relation to his own followers as well as the peasants in the neighborhood was characterized by the attempt to distribute among them, especially among the poorest, the property, mainly Jewish, which had been plundered and collected in the small towns.

A constant handicap under which General Denikin had to struggle was the disturbance to his rear by the hostile attitude of unfriendly populations, replete with propaganda to attain some national aim. Under this category came the hostility of General Petlura, the peasant Ukrainian leader, between whom and Denikin a state of war had been declared. But Petlura was far from being Denikin's only opposer in South Russia. Three Ukrainian bands had been operating for some time behind his lines, robbing stragglers and holding up trains. Of these, the most formidable was the band of Shubé, which attacked trains between Kiev and Poltava, and the band of Makhno, in the Province of Ekaterinoslav, which was said to be anti-Semitic. But Makhno personally condemned discrimination of any sort, and punishments for anti-Semitic acts were swift and severe.

From the earliest reports it became evident Makhno understood the peasant mind, and so had started out with nothing more than the simple statement that every peasant must have land, and every house a master — first principles which any peasant could understand.

Makhno was quoted by the monarchists as saying that a country is simply a great house, so it, too, must have its master — and who, save the Czar, could be master of a country? Which brief statement, said the monarchists, being the sum and substance of the political and economic ideas of all peasants, it was indeed small wonder that they flocked to Makhno. All of which quotations might be very well, save for the fact that Makhno never said anything of the sort.

On the contrary, when one actually got into the Makhno country, one learned very definitely that Makhno had pronounced himself very bitterly opposed to any monarchy and confined his very sketchy political pronouncement to rather indefinite talk about freedom, and cries of "Down with the landlords!" but also "Down with the Bolsheviki!"

Then, when his band had grown to a considerable size but not yet big enough to face the Bolshevist Army which was bearing down on him, he told his men to evaporate, to go back and till the fields, and to reassemble at a time and place he would announce later. So his army was placed in reserve by the simple process of turning the horses homeward and taking off the saddle and hooking up the plow. But the great point is that the army did reassemble at the time and place designated, and promptly recommenced operations.

There is evidence that he has followed this same general procedure each year, for at times his forces consist of but a handful, and then within a fortnight they develop into an army of forty to fifty thousand. The reason for this is, that he understood perfectly that a campaign in spring and fall would attract few peasants, since the work in the fields then required all their attention. Accordingly, at those times he ordered his followers home to till and harvest their fields, and this accomplished, to rendezvous at time and place to be notified to them — with their horses, provisions, and all the arms and ammunition they can get together. That this system, which sounds so haphazard, actually functioned, was shown by the very definite evidence of the great havoc he worked with the Bolshevist communication trains, and by the fact that after every disappearance he has reappeared the stronger.

His troops were all cavalry; his commissariat is the simplest thing in the world, in the first place, because his campaigns were short and he sent his men home as soon as the fighting season was over, and secondly, because he had the support of the peasantry and so can subsist his troops on the provision which they brought with them when they assembled, plus the gifts of the peasantry and the results of the captures of Bolshevist supply trains.

He did not believe in artillery, and rifles he described as useless except as a stop-gap for a deficiency in machine-guns. So the only arms his forces carried are sabres and machine guns. For the latter, he developed various ingenious mounts, such as very rugged little trucks and wheelbarrows with the wheel amidships; but his favorite mount was the back of an ordinary light, high-wheeled buggy or surrey, such as was found everywhere in Russia. All of which procedure was of course most unorthodox, but it was based on a very keen understanding of his forces, the character of the country in which they were operating, and what they were to do. [let them that hath understanding see here the forerunner of the modern "technical"]

His usual procedure when starting operations, was to dash up to a village in great style — fine horses, fine carriages or sleighs, fine furs, and rugs—for he realizes the importance the peasants attach to these trappings. As soon as the peasants have gathered about him, he makes a short and very much to the point speech, for he had grasped the point that though the Russians dearly love to listen to long speeches, they pay precious little attention to them as far as action is concerned when it comes to the question of doing something.

Then, what they really want, are short, crisp, simple sentences with plenty of meat in them—and simple ideas capable of being acted on at once. For instance, he will say: "Look at this town, its filthy streets, its heaps of rubbish, its shortage of water, the frightful condition of the sewers! Whose fault is this? Obviously the officials whom we pay to take care of these things. Down with these officials! Kill these officials!"

Makhno captured towns in which he would allow his followers a day to loot the rich, but under most drastic threats as to what he would do if they touched the poor—threats which he as drastically carried out. He was called a robber and a thief, but if this be so, he at least made a virtue of it; for time and again he has robbed the rich only to distribute the plunder among the poor, saying he but gave them what was theirs by right — again a very popular doctrine among the numerous poor, even if not so agreeable to the few rich, who, here as elsewhere, got little sympathy in such matters. So, small wonder that he was so enormously popular, and that he had success while armies, superior in every other way, but lacking a leader with such simple common sense and common understanding, had been pushed into the sea.

As regards the Soviet power he was the typical representative of the temper prevailing among the middle peasants. He never stood on the side of the Soviet government. During the first period, after the fall of the German rule, he supported the Soviet power because he regarded it as stronger and more consistent than the Directory, but he opposed it as being a city power. At the same time he was an opponent of the volunteer army of Denikin, an oppressor of the peasants and fighter for the reestablishment of the pre-revolutionary order.

At the beginning of 1918 the Bolshevist commissary, Dybenko, supplied Makhno with a large quantity of arms, including no fewer than 300 machine guns. Makhno was constantly either quarrelling with, or being reconciled with Trotzky. Later he again became reconciled with the Bolsheviki, and, supported by criminal elements, created disorder in the rear of Denikine's Army.

At times he and his bands opposed equally Denikin's volunteers, Petljura's Ukrainian forces, and the Bolsheviki. Among the latter he made many converts. Assembling speedily under arms when needed for some military enterprise, his troops became again, to all appearances, peaceful villagers, as soon as the immediate need for their service passed. Makhno's 'invisible army' was said to number some forty thousand men, including many intellectuals. No one received regular pay, but the booty taken in their campaigns was shared equally by all.

Makhno also slaughtered Jews, played the part of a Robin Hood, and was said to be immensely popular with the peasants. He sometimes fought the Red armies, and even massacred the Communists, but he also opposed Denikin and Wrangel. He objects to any regular or civilized government, " smashes " for choice, fights and loots as a guerrilla, and reflects the untaught, native, peasant view of freedom and the people's cause. These heroes flourish in the south, partly because Communism is weak there and partly because in the south there is still much to loot.

The Bolsheviki promised a reward of ten million rubles for the capture of Makhno, dead or alive. According to the London Times: " ... the Soviet sent a delegation to him with peace proposals. Of this meeting the Soviet newspaper Bednota gave the following report: 'Makhno has agreed to the proposals on one condition - namely, all the peasants are to be asked what form of government they prefer. Whichever they choose they must get.' After this the negotiations fell through."

General Wrangel issued an order in which he suggested that his troops should 'cooperate with any anti-Bolshevist bodies.' In this order he does not mention Makhno by name. In reply Makhno issued an order to his supporters and the peasants at large that they should' assist all anti-Bolshevist forces.' The land laws drawn up by General Wrangel were largely instrumental in producing this favorable reply. As long as this tacit agreement held good, the Bolsheviki were never able to force the approaches to the Crimea, and were quite unable to apply their usual methods for creating disturbances in his rear. And so this small, fair-haired Russian, aged about forty, of simple parentage, who passed no fewer than six years as a prisoner in Siberia (some say for political and others for criminal offenses), provided General Wrangel with the sympathy of the Russian peasant.

By October 1919 , Makhno, after having been defeated north of Odessa, had returned to his old haunts, the eastern side of the Dnieper and the region north of the Sea of Azov, and had raided several towns in Daghestan, in Northeastern Caucasus, where an insurrection movement had begun. Denikin had dispatched troops to this spot to put down the insurrection and capture the bandit leader. On 29 October 1919 a Moscow wireless reported that large bodies of both Petlura’s and Makhno's forces were joining the Red Army. Several towns along the Dnieper had been taken by the insurgents southeast of Kiev, while Makhno had captured Alexandrovsk and was besieging Elizabetgrad.

Makhno and his forces helped bottle up the last of the White Armies in the Ukraine led by General Wrangel in the Crimea in 1920. The Black Flag that fluttered over Sevastopol alongside that of the Reds when Wrangel evacuated his defeated refugee forces on November 14, 1920. In a carefully constructed move just two weeks after Wrangle's defeat, the Bolsheviks liquidated Makhno's senior leadership across a broad expanse of the Ukraine. The Red Army began open warfare on the Black Flag units and Makhno again found himself a hunted man.

By 1921 Ukraine could be divided into two parts: that to the right, and that to the left of the Dnieper. The right bank was the base for the bandit hordes of the Petlurian chauvinist stamp. Banditry on the left bank was more anarchistic in its nature (as is illustrated by the case of Makhno). As Petlura lost in popularity, the political movement resolved itself into an organization of military detachments, with whose aid Petlura and his adherents attempted to conquer Ukraine. In consequence of the pronounced transformation among the peasants, these detachments changed into small bands of robbers, whose numbers shrank day by day.

Makhno's detachments, after Wrangel's defeat, had to seek other allies in Russian territory. They tried the Don region, but found insufficient anti-Bolshevist forces there. Then they turned east, to Antonov, but found no help there. They tried Kursk, but encountered only scant sympathy. So they found themselves constrained to move their "forces" abroad. At first Makhno's detachments thought of going into Poland. Then they decided to go to Rumania. But would that make any difference? As far as Soviet Russia is concerned, Poland and Rumania are merely two rooms of the same house.

By August 1921, with his force dwindled to just fifty beaten followers, he crossed the border into exile in the Rumanian. Makhno eventually lived in exile among the very White Russians that he helped defeat. He wrote two books on anarchism and his activities. Makhno lived his remaining years in obscurity, poverty, and disease, working in an automobile factory, a restless consumptive for whom drink provided meager relief until he died. He died as he had lived, improverished, in 1934 of the tuberculosis he acquired in the Tsar's Butyrki prison as a teenager.

Makhno continued his struggle for his ideals in emigration. He had a considerable influence on the development of the world anarchist movement, which was soon to give battle to fascism in Spain.

Makhno came to Europe penniless, in one tunic. Makhno moonlighted as a joiner , carpenter , even weaving house slippers. On July 6 (according to other sources, July 25), 1934, Nestor Makhno, at the age of 45, died in a Paris hospital from bone tuberculosis.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|