Cimmerian - 900 BC - 600 BC

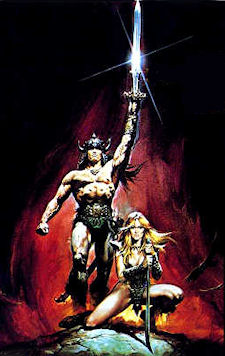

"Between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities and the rise of the sons of Arias, there was an Age undreamed of, when shining kingdoms lay spread across the world like blue mantles beneath the stars. . . . Hither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand . . . to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet."

"Between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities and the rise of the sons of Arias, there was an Age undreamed of, when shining kingdoms lay spread across the world like blue mantles beneath the stars. . . . Hither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand . . . to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet." Conan the Cimmerian-the boy-thief who became a mercenary, who fought and loved his way across fabled lands to become King of Aquilonia. Neither supernatural fiends nor demonic sorcery could oppose the barbarian warrior as he wielded his mighty sword and dispatched his enemies to a bloody doom on the battlefields of the legendary Hyborian age. Conan's era was around 9000 BC, with embellishments from many other eras. The Hyborian age is an epoch where people called 'noble' are debauched and corrupt and people labelled as 'savage' are honourable and straight-forward.

Beginning in the December 1932 issue of Weird Tales and in 17 more stories to follow, Robert E. Howard told of Conan (a Celtic name) of Cimmeria, a mighty sword-wielding swashbuckler who roamed primeval Europe and Africa in the "Hyborian Age". Howard's Conan stories have a madness and a ferocious joy that no other writer has matched. The Conan saga is not a unified Joseph Campbell style hero's journey such as "Star Wars" or "Lord of the Rings". Rather, it's more akin to James Bond. Each story can be read and enjoyed on its own, without any prior knowledge of the events or characters in previous stories. In no Conan story are the plot details of any other Conan story ever even mentioned, except in the most general of terms.

Robert E. Howard is one of the most famous and influential pulp authors of the twentieth century. Though largely known as the man who invented the sword-and-sorcery genre-and for his iconic hero Conan the Cimmerian-Howard also wrote horror tales, desert adventures, detective yarns, epic poetry, and more. In a meteoric career that covered only a dozen years, Robert E. Howard defined the sword-and-sorcery genre. Howard found school confining and hated having anyone in authority over him. Robert E. Howard's mother was terminally ill with tuberculosis, and was slowly dying throughout Howard's entire life. Her declining health cemented his view of existence as heartless, unfair, and ultimately futile. When he learned that his mother had entered a coma from which she was not expected to wake, Howard committed suicide in 1936 at the age of thirty. The prolific writer, whose stories were full of men facing death on their own terms, wanted to do the same.

Cimmerians (Kimmeriori), were a people who belonged partly to legend and partly to history. In Homer's Odyssey (book 11) they are a fabulous people living on the edge of the world by the shore of Oceanus, shrouded in mist and in perpetual darkness. Cimmerians were a nomadic, Iranian-speaking peoples who occupied the North Pontic steppe zone from the Don to the Danube, with their center in the Crimea. Their culture and civilization flourished between about 1000 and 800 BC.

Originally, the Cimmerians may have lived in southern Ukraine, where the Crimea is, according to some scholars, still called after the Cimmerians. Archaeologists have identified them with the Novocerkassk culture on the grass plains between the river Prut and the Lower Don (c.900-c.650 BCE). The Cimmerians raided the Greek towns in Aeolia and Ionia, looted Paphlagonia, and captured Sinope. After 640, Lygdamis attacked Assyria twice, but was defeated. Another defeat was inflicted upon them by the Lydian king Alyattes (c.600-560), after which the Cimmerians disappear from history.

Originally, the Cimmerians may have lived in southern Ukraine, where the Crimea is, according to some scholars, still called after the Cimmerians. Archaeologists have identified them with the Novocerkassk culture on the grass plains between the river Prut and the Lower Don (c.900-c.650 BCE). The Cimmerians raided the Greek towns in Aeolia and Ionia, looted Paphlagonia, and captured Sinope. After 640, Lygdamis attacked Assyria twice, but was defeated. Another defeat was inflicted upon them by the Lydian king Alyattes (c.600-560), after which the Cimmerians disappear from history.

Homer mentions a people of the name of Cimmerii, in whose country he places his Hell; and there can be no doubt that their name has a connexion with this circumstance. In Coptic there is found the word Chemi, in Hebrew Chum, and in Arabic Kahm, all signifying black, which, with the Persic Ea, the mark of the oblique case, and the Sanskrit Jan, a man or person, the common termination of nouns ethnical, forms Cimmerian, that is, a person living in a high northern latitude, in the vicinity of .the six months' night which reigns within the Polar Circle. That this fact was known to Herodotus there can be no doubt whatever, as he mentions a race of men dwelling to the north of the Argippaei, who slept away six months of the year. The modern name of the country is Tartary, formed by doubling the Persic word Tar, darkness, or blackness, with the signification of darkness of darkness, whence the Greek Tartarus, a name of hell itself.

The ancients differed in opinion as regarded the orthography of the name Cimmerii. Modern scholars arc in like manner divided as to the derivation of the term "Cimmerian" itself. It is maintained by some of these that the Greeks obtained their first knowledge of this race from the Phoenicians, and that hence, in all probability, the stories told of the gloom which enshrouded the Cimmerian land, and of the other appalling circumstances connected with the people, were mere Phoenician inventions to deter the Grecian traders from visiting them. In accordance with this idea, Bochart derives the word " Cimmerian" from the Phoenician kamar, or hammer. Hence we read of Cimmerians, not onlv in Lower Asia, hut also in the remotest west and north. "The Cimmerians," says Eustathius. "are a people in the west, on the Oceanus : they dwell not far from Hades."

Another class of etymologists, however deduce the word in question from the Celtic, and make the Cimmerii identical with the Kimri, whence the later Cimbri. The Cimmerians, therefore, who overran Asia Minor, would be a Celtic race. There is something extremely plausible in this supposition, and in this way, too, we may, without having recourse to Bochart's derivation, account for the existence of Cimmerii. or Celts, in the remote west.

Another class of etymologists, however deduce the word in question from the Celtic, and make the Cimmerii identical with the Kimri, whence the later Cimbri. The Cimmerians, therefore, who overran Asia Minor, would be a Celtic race. There is something extremely plausible in this supposition, and in this way, too, we may, without having recourse to Bochart's derivation, account for the existence of Cimmerii. or Celts, in the remote west.

Cimmerians were a nomadic race of Upper Asia, who appear to have originally inhabited a part of what is now called Tartaru. The name of Cimmeria, at an early period, was doubtless one of very wide application; but in Herodotus's time it appears to have been restricted to the country known as Crim Tartary, or the Crimea. The same name is also given to a whole district, as well as to a narrow sea, that is, to the Cimmerian Chersonesus and the Cimmerian Bosphoras.

According to Herodotus (1, 15), they were driven from their primitive scats by the Scythians and moved down, in consequence, upon Asia Minor, which they invaded and ravaged during the reign of Ardys, king of Lydia, the successor of Gyges. The Cimmerian attack upon Ionia, which was earlier than Croesus, was not a conquest of the cities, but only an inroad for plundering.

In flying from their Scythian foes, the Cimmerians took their course by the sea-coasts to Sinope, and the Cimmerian Bosphorus, and as, after this flight, the old Cimmerian league was broken up, and the tribes dispersed. While the Scythians invaded them, they quarrelled among themselves whether to fight or fly, and settled the dispute by fighting each other, and flying from the enemy.

Strabo says Homer has placed the Cimmerians in the neighbourhood of Hell, knowing that they inhabited dark and northern regions near the Bosphorus. Perhaps also he was induced to place them there by the hatred which all the Ionians cherish against that nation, for it is pretended that the Cimmerians made an incursion into Ionia and AEolia in Homer's time, or shortly before the period of his birth. Strabo places the incursion of the Cimmerians in the time of Homer, or a little before the birth of the poet. (Strab., 20.) Wesseling thinks the authority of Strabo inferior to that of Herodotus ; but Larcher inclines to the opinion that two different incursions are spoken of, an earlier and a later one. He makes the former of these even anterior to the time assigned by Strabo, and thinks it preceded by a short period the siege of Troy. He supposes this, moreover, to be the one alluded to by Euripides. According to this view of the subject, Herodotus speaks, merely of the latter of these two inroads.

The incursions of the Cimmerians into Asia Minor and their establishment in Cappadocia must bo placed at the least beforo the year 705 BC; the devastation of Phrygia by the Cimmerians was in the year 695 BC. According to the dates of Eusobius Midas (the husband of Damodike) began to reign in Olymp. 10, 3 = 738, and took his own life in 01. 21,2 = 695 (Euseb. ed. Schone, 2, 82, 85); his reign extended therefore from 738 to 695 BC. Hence the devastation of Phrygia by the Cimmerians must have taken place in the year 695.

The account given by Herodotus is, that the Cimmerians, when they came into Asia Minor, took Sardis, with the exception of the citadel, and that they were finally expelled by Alyattes, the contemporary of Cyaxares. (Herod., 1, 15, seq.) The same historian makes the Cimmerians to have dwelt originally in the neighbourhood of the Palus Maseotis and Cimmerian Bosporus, and when driven out "from Europe," as he expresses himself, by the Scythians, to have fled along the upper shore of the Euxine to Colchis, and thence to have passed into Asia Minor. (Herod., 1, 103.)

Volney maintains that there were two incursions of the Cimmerians, but he places the first of these in the reign of Ardys (699 BC), to which he thinks Herodotus alludes in the fifteenth chapter of his first book ; and the second one in the time of Alyattes and Cyaxares, which he supposes to be the inroad alluded to by Herodotus in the one hundred and third chapter of the same book. In 640 BCE Cimmerians attacked the Ionian cities of Smyrna, Magnesia and Ephesus. The Greek poets Callinus and Archilochus bear witness to the terror they inspired in Ionia. Then plague struck them and they retreated east. Some who remained were finally expelled about 600 BC by Alyattes (616, BC), king of Lydia, by whom these barbarians were expelled from the Asiatic peninsula, after which the Cimmerians disappear from history. It appears reasonable to refer all to but one invasion on the part of the Cimmerians, commencing in the time of Ardys.

Herodotus says there are still to be found in Scythia walls and bridges, which are termed Cimmerian. There are even to this day in Scythia fortifications and "Porthmia", which retain the name of Cimmerian, together with a whole province, and a bosphorus or narrow sea. It appears certain that the Cimmerians fled from the Scythians into Asia, and settled in that peninsula where the city of Sinope, a colony of the Grecians, was afterwards built; and it is no less evident that the Scythians, pursuing them, mistook their way and entered Media: for the Cimmerians, in all their flight, never abandoned the coast of the sea; whereas the Scythians in their pursuit leaving mount Caucasus on the right hand, deflected towards the midland countries, and so entered Media. This report is generally current, as well among the Grecians as Barbarians.

Respecting the walls still found in the time of Herodotus under the name of Cimmerian, he does not say that they were in the peninsula, but the context implies it, and it is not improbable that he had seen them. Baron Tott saw in the mountainous part of the Crimea, ancient castles and other buildings, a part of which were excavated from the live rock, together with subterraneous passages from one to the other. These were, he says, always on mountains difficult of access. He refers them to the Genoese; with what justice we know not; it is possible they might have wade use of them, but it is more probable that these are the works alluded to by our author, for it may be remarked that works of this kind are commonly of very ancient date.

Respecting the walls still found in the time of Herodotus under the name of Cimmerian, he does not say that they were in the peninsula, but the context implies it, and it is not improbable that he had seen them. Baron Tott saw in the mountainous part of the Crimea, ancient castles and other buildings, a part of which were excavated from the live rock, together with subterraneous passages from one to the other. These were, he says, always on mountains difficult of access. He refers them to the Genoese; with what justice we know not; it is possible they might have wade use of them, but it is more probable that these are the works alluded to by our author, for it may be remarked that works of this kind are commonly of very ancient date.

Niebuhr, with very good reason, insists that Herodotus has there fallen into an error, and that all the wandering peoples which have in succession occupied the regions of Scythia, have, when driven out by other tribes from the east, moved forth in a western direction towards the country around the Danube. The Cimmerians, therefore, must have come into Asia Minor from the east. As regards the name of the Cimmerian Bosporus, the same acute critic supposes it to have arisen from the circumstance of a part of the Cimmerian horde having been left in this quarter, and having continued to occupy the Tauric Chersonese as late as the settlement of the Greek colonies in these parts.

The Behistun Inscription is to cuneiform what the Rosetta Stone is to Egyptian hieroglyphs: the document most crucial in the decipherment of a previously lost script. It is located in the Kermanshah Province of Iran. The inscription of Behistun is in three languages and an Aramaic version of it has been found at Elephantine in Egypt. The decipherment by Rawlinson of the inscription of Behistun in 1837 opened the way for the interpretation of the whole series of inscriptions, cuneiform tablets and other records which had been unearthed. Since 1840 or 1850 archaeology practically created four thousand years of history: a new heaven as well as a new earth for the pre-Hellenic world. Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, the Hittites emerged from an almost Cimmerian darkness.

As early as the closing years of Sargon's reign, the Cimmerians were pressing hard on Urartu and were overrunning the empire, whose power had been already broken by Assyria. It may be conjectured that the violent death which Sargon met in some unknown place was perhaps the result of the signal defeat inflicted on an Assyrian army by the Cimmerians. This disaster re-echoed throughout the whole East, and is referred to in a hymn of victory which has been preserved in the book of Isaiah (xiv. 4-21). Assyria was afraid of the intruders, and with difficulty guarded her frontiers against her new antagonists, though from the first the objective of the Cimmerian advance was Asia Minor more than Assyria.

This was the beginning of the great Cimmerian movement which partly obliterated the states of Asia Minor, or Phrygia, and partly inundated them. Lydia was overrun, and only the citadel of Sardis was able to hold out. The Cimmerians then devastated Asia Minor for a time, until their power broke up and gave way before the newly rallied forces of the civilised nations. One of their leaders, Dygdamis, is known to us from classical history. The Ionian towns had also to suffer from the wild hordes, and the destruction of Magnesia finds an echo in the poems of Archilochus. This Dygdamis, mentioned in an inscription of Ashurbanipalj met his death, according to the classical account, in Cilicia-pcssibly Homer's Cilicia in the Troad; he was succeeded by his son Sandakshatra. The Cimmerian onslaught gradually spent itself in distant regions, and the remains of it were dispersed by the Lydians.

When the great tide of Scythian invasion swept from Asia over the great Russian plain, it bore down upon the northern shores of the Black Sea. where the people known as the Cimmerians dwelt. These people were closely allied to the Thracians. To Thrace naturally they turned their steps, flying from the terrible Scythian invaders. Their kinsmen in Thrace made common cause with them. The allied forces crossed to Asia, as many Thracian tribes had previously done, and the descendants of these Thracian Tribes in Asia Minor joined them and shared their conquests. In Bithynia and in the Troad these Asiatic Thracians had settled. The united forces of Cimmerians and Thracians marched on Phrygia.

King Mita, dreading their approach, killed himself, the legend says, by drinking bull's blood. Sinope was next assailed. In a little time the territories conquered marched with the territories of the Assyrian king, who had advanced his frontiers to the Halys. On the banks of the Halys was fought the great battle which turned back the tide of Cimmerian invasion from the borders of Assyria. In this contest against the "Gimirrai," as the Assyrians called them. King Esarhaddon won a complete victory and secured the safety of his dominions from the barbarian onset in 679 BC. The invaders, repulsed from the east, then turned on Lydia. Gyges in terror implored the aid of the Assyrians. The aid was promised on condition that Gyges would do homage to the Assyrian monarch and acknowledge his suzerainty. The Cimmerians and Thracians were repulsed, the Assyrians having abstained from lending any other aid than their prayers, so Gyges repudiated the suzerainty in 660 B.C. He was then abandoned to his fate by his former allies. Psammetichus of Egypt, to whom he had sent help to throw off the yoke of Assyria.

The Cimmerians soon burst upon his kingdom. This time the barbarians met with little opposition. Gyges fell in battle. His capital, Sardis, surrendered. The hordes of invaders were let loose upon the Greek settlements. Ionia was overrun, Magnesia was destroyed, and the temple of Artemis at Ephesus was burnt, while towns on all sides were given up to plunder and devastation. "It was a raid and not a subjugation of the towns," says Herodotus, and his words are true in so far as they apply to the conduct of the invaders after the conquest of Lydia; but the Lydian war itself was in no way a raid, but a regular struggle between organised powers. Besides, the occupation of the northern and eastern territories of Lydia was permanent. King followed king, no doubt, on the Lydian throne. To Gyges succeeded his son Ardys; to him in turn his son Sadyattes.

But the Cimmerians held firm hold of their conquests through these two reigns. It was only during the reign of Alyattes, the successor of Sadyattes, that Lydia finally expelled the Cimmerians. Alyattes freed Lydia and all Asia Minor from the bondage which the barbarians had imposed. Whether the Cimmerians wandered back to their old homes or sank into servitude in Lydia or were allowed to blend with the inhabitants no one can now say. But with the liberation of Lydia by Alyattes their career as a conquering nation closed, and as such history knows them no more.

After the reign of Sargon II, the Khumri are no longer mentioned in the Assyrian records. That the Cimmerians were in the Black Sea area before the Scythians is an historic fact.They were the vanguard of the thrust to the west. The greater part of the Cimmerians moved up the Danube.

For students of the Lost Tribes of Israel, the inscription has provided an invaluable missing link. George Rawlinson, connected the Saka/Gimiri of the Behistun Inscription with deported Israelites: "³We have reasonable grounds for regarding the Gimirri, or Cimmerians, who first appeared on the confines of Assyria and Media in the seventh century B.C., and the Sacae of the Behistun Rock, nearly two centuries later, as identical with the Beth-Khumree of Samaria, or the Ten Tribes of the House of Israel." [George Rawlinson, note in his translation of History of Herodotus, Book VII, p. 378]. While British-Israelism identifies some of the Lost Tribes with the Cimmerians, and the Cimmerians with the Celts, they also trace the rest of the House of Israel, through the Scythian line, to the Germanic Anglo-Saxon tribes. The Scythians pushed the Cimmerians north and west, across the plains of Europe, where it is said the Cimmerians become known as the Celts.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|