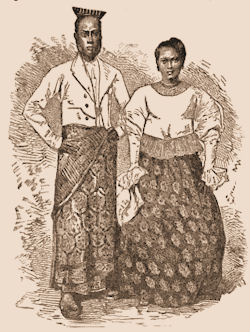

Sri Lanka - Burghers

The term Burgher was applied during the period of Dutch rule to European nationals living in Sri Lanka. By extension it came to signify any permanent resident of the country who could trace ancestry back to Europe. This term, dating from the days of the Dutch, is commonly applied in Ceylon to people of mixed European and native descent, in fact as the term Eurasian is used in India, but strictly it applies to descendants of the Dutch, some of whom are quite white, and have no native blood in their veins.

The term Burgher was applied during the period of Dutch rule to European nationals living in Sri Lanka. By extension it came to signify any permanent resident of the country who could trace ancestry back to Europe. This term, dating from the days of the Dutch, is commonly applied in Ceylon to people of mixed European and native descent, in fact as the term Eurasian is used in India, but strictly it applies to descendants of the Dutch, some of whom are quite white, and have no native blood in their veins.

At the time Ceylon passed from Dutch to British control, in 1797, the denomination Burghers comprehended Europeans, and descendants of Europeans, not being Englishmen, in the service of Government; descendants of Europeans and native women; children of Ceylonese or Malabars, who have become Christians, and (although very seldom the case) have changed their dress, and assumed that of Europeans; (these are not distinguished from those who are called Portuguese;) and, lastly, descendants of slaves made free by their masters. These Burghers are chiefly established in the principal towns—Colombo, Jaflhapatam, Point de Galle, Trincomal£, Matura, Caltura, Negombo, and Manar. They are, for the most part, concerned in trade; some are employed as clerks in the public offices; few of them are possessors of land. Their number of males and females did not exceed five or six thousand.

Many of those who were employed in the service of the Dutch Government, and remained in the island when it passed under the English East-India Company, were considered as Burghers, and formed a considerable part of that body. Their condition was naturally very indifferent: many of them, indeed, were reduced to great poverty. Those Europeans, also, who were formerly concerned in trade, had not improved their circumstances by the change.

All the servants of the Dutch Government were carrying on trade, and lent out their capitals, upon high interest, to the natives. Their manner of living was by no means expensive: their salaries were very trifling; for the Governor had but 300 florins (not quite £.30 sterling) per month, and although some of them amassed considerable wealth, by fees and other privileges granted or connived at by their Government, yet their frugal habits of life prevented much of that wealth being dispersed in the country.

In consequence of it, the natives were kept in poverty, and had not the means to collect capitals sufficient to trade with. The few who followed commerce borrowed the capitals from the Dutch, most frequently on very high interest; or, what was even more common, traded for the opulent Dutch, as their agents, and were compelled to satisfy themselves with a very indifferent part of the profits given to them as their commission. The great bulk of the commerce of Ceylon was therefore in the hands of those Public Servants, or of the principal Burghers with whom these were connected.

The arrival of a great number of English Civil and Military Servants, themselves not connected in trade, and spending almost the whole of their salaries, had the effect of raising considerably the price of all the productions of the soil. As but few of the Burghers were proprietors of land, they did not benefit by this increase of prices: on the contrary, it has reduced them to poverty.

Eventually the term Burgher included both Dutch Burghers and Portuguese Burghers. Unlike their confreres in India, by 1900 the Burghers were in a very powerful position in Ceylon, and in 1907 had a member in the Legislative Council. In Colombo especially, the Burghers may almost be divided into two classes, the poorer Portuguese Burghers, many of whom speak to this day a dialect of Portuguese, and the richer Dutch Burghers, who form a great community largely filling the posts of clerks in offices, and have been described as the brazen wheels of the executive that keep the golden hands in motion. The great line of work adopted by the better-to-do Burghers is the practice of one of the professions of law or medicine, and many of the ablest lawyers, physicians, and surgeons in the island belong to this race.

Always proud of their racial origins, the Burghers further distanced themselves from the mass of Sri Lankan citizens by immersing themselves in European culture, speaking the language of the current European colonial government, and dominating the best colonial educational and administrative positions. They have generally remained Christians and live in urban locations. Since independence, however, the Burgher community has lost influence and in turn has been shrinking in size because of emigration. In 1981 the Burghers made up .3 percent (39,374 people) of the population.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|