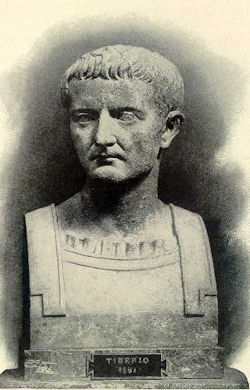

Tiberius Claudius Nero Caesar

Tiberius (Tiberius Claudius Nero Caesar) (42 BC-37 AD). The second Emperor of Rome (14-37 A.D.). He was the son of Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia Drusilla, and was adopted by Augustus when the latter married Livia in 38 BC, after her compulsory divorce. He was carefully educated, and early manifested intellectual power and military skill. His first important command was the expedition sent in 20 BC to restore Tigranes to the throne of Armenia.

Tiberius (Tiberius Claudius Nero Caesar) (42 BC-37 AD). The second Emperor of Rome (14-37 A.D.). He was the son of Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia Drusilla, and was adopted by Augustus when the latter married Livia in 38 BC, after her compulsory divorce. He was carefully educated, and early manifested intellectual power and military skill. His first important command was the expedition sent in 20 BC to restore Tigranes to the throne of Armenia.

A more noteworthy commission was given him in 15 BC, when, in company with his younger brother Drusus, he defeated the Rhaetians. Two years later he was consul with P. Quintilius Varus, and in 11 BC he fought successfully against the Dalmatians and Pannonians. The death of Drusus in 9 B.C. recalled Tiberius to Germany, but in 7 BC he held the consulship for the second time.

The troubles which were to overshadow his life had, however, already begun. In 11 BC he had been forced by Augustus to divorce his wife, Vipsania Agrippina, whom he loved deeply, and to marry the Emperor's daughter Julia, the widow of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. Her conduct, and perhaps his own jealousy of the growing favor of Gaius and Lucius Cesar, the two grandsons of Augustus, children of Julia and Agrippa, led him to retire, against the Emperor's will, to Rhodes in 6 BC, the year in which the tribunician power was conferred upon him for five years.

He remained in Rhodes seven years, and before his return Julia had been banished for life to the island of Pandataria. The death of Lucius Caesar in 2 AD and of Gaius in 4 AD led Augustus to adopt Tiberius as his heir. From this time until the Emperor's death Tiberius was in command of the Roman armies, and campaign followed campaign. In 4 AD he reduced Germany from the Rhine to the Elbe, from 6 to 9 he waged war again in Dalmatia and Pannonia, and from 10 to 11 he held the Rhine against the Germans who had defeated Varus. In 12 AD he was honored with a well earned triumph.

When the death of Augustus occurred, August 19, 14, Tiberius was on his way to Illyricum. He was summoned home by his mother, and at once assumed control of the Empire. Despite his execution of Postumus Agrippa, the grandson of Augustus, his reign was at first beneficent. Gradually, however, a change took place in Tiberius. He minimized the power of the people, and transferred the election of magistrates from them to the Senate. At the same time he watched with suspicion the increasing popularity of Germanicus Caesar, his nephew. In 19 Germanicus died, poisoned, reports current at the time declared, at the instigation of his uncle.

About this time the evil genius of the reign of Tiberius, AElius Sejanus, gained his ascendancy over the Emperor. Under his influence a system of espionage was instituted which doomed all who in any way opposed Tiberius. Freedom was abolished in Rome, the Senate was demoralized, and the Emperor sank to the level of a cruel and ruthless tyrant. In 23 Sejanus abetted the murder of the only son of Tiberius, Drusus Caesar. Three years later the Emperor left Rome with Sejanus, going first to Campania and in 27 to Capri, where he remained till his death.

In 29 Livia Drusilla died, thus removing one of the last barriers to the complete degeneration of her son. Two years later Tiberius learned of the treachery and ambition of Sejanus, who was put to death, only to be replaced by Macro, as corrupt as his predecessor. In 37 Tiberius' died, smothered, though already on bis death bed, by Macro, and was succeeded by Caligula. The reign of Tiberius was beneficial to the Empire at large, and the provinces especially flourished under his sway. Only in Rome, and only where his personal interests were at stake, was he merciless.

After discussing Tiberius’ retirement to the island of Capri, Suetonius (Tib. 43-45) divulges the following details about Tiberius’ reclusively licentious behavior:

“On retiring to Capreae he made himself a private sporting-house, where sexual extravagances were practiced for his secret pleasure. Bevies of girls and young men, whom he had collected from all over the Empire as adepts in unnatural practices, and known as spintriae, would copulate before him in groups of three, to excite his waning passions. A number of small rooms were furnished with the most indecent pictures and statuary obtainable, also certain erotic manuals from Elephantis in Egypt; the inmates of the establishment would know from these exactly what was expected of them. He furthermore devised little nooks of lechery in the woods and glades of the island, and had boys and girls dressed up as Pans and nymphs prostituting themselves in from of caverns or grottoes; so that the island was now openly and generally called ‘Caprineum.’

"Some aspects of his criminal obscenity are almost too vile to discuss, much less believe. Imagine training little boys, whom he called his ‘minnows,’ to chase him while he went swimming and to get between his legs to lick and nibble him. Or letting babies not yet weaned from their mother’s breast suck at his breast or groin – such a filthy old man he had become! Then there was a painting by Parrhasius, which had been bequeathed him on condition that, if he did not like the subject, he could have 10,000 gold pieces instead. Tiberius not only preferred to keep the picture but hung it in his bedroom. It showed Atalanta performing fellatio with Meleager.

"The story goes that once, while sacrificing, he took an erotic fancy to the acolyte who carried the incense casket, and could hardly wait for the ceremony to end before hurrying him and his brother, the sacred trumpeter, out of the temple and indecently assaulting them both. When they jointly protested at this disgusting behavior, he had their legs broken.

"What nasty tricks he used to play on women, even those of high rank, is clearly seen in the case of Mallonia whom he summoned to his bed. She showed such an invincible repugnance to complying with his lusts that he set informers on her track and during her very trial continued to shout: ‘Are you sorry?’ Finally she left the court and went home; there she stabbed herself to death after a violent tirade against that ‘filthy-mouthed, hairy, stinking old man.’

The writings of Tiberius have been lost. His style is said to have been obscure, archaic, and affected. He wrote a brief autobiography, a lyric on the death of Lucius Caesar, and a number of Greek poems.

Historians of Rome in ancient times remembered Tiberius chiefly as the sovereign under whose rule prosecutions for treason on slight pretexts first became rife, and the hateful xacc of informers was first allowed to fatten on the gains of judicial murder. Augustus had allowed considerable licence of speech and writing against himself, and had made no attempt to set up a doctrine of constructive treason. But the history of the state trials of Tiberius's reign shows conclusively that the straining of the law proceeded in the first instance from the eager flattery of the senate, was in the earlier days checked and controlled to a great extent by the emperor, and was by him acquiesced in at the end of his reign, with a sort of contemptuous indifference, till he developed, under the influence of his fears, a readiness to shed blood.

The principal authorities for the reign of Tiberius are Tacitus and Suetonius. Suetonius was a biographer rather than an historian, and the ancient biographer was even less given to exhaustive inquiry than the ancient historian; moreover Suetonius was not gifted with great critical faculty, though he told the truth so far as he could see it. His Lives of the Twelve Caesars was written nearly at the time when Tacitus was composing the Annals, but was published a little later.

The Annals of Tacitus were not published till nearly eighty years after the death of Tiberius. He rarely quotes an authority by name. In all probability he drew most largely from other historians who had preceded him; to some extent he availed himself of oral tradition; and of archives and original records he made some, but comparatively little, use. In his history of Tiberius two influences were at work, in almost equal strength: on the one hand he strives continually after fairness; on the other the bias of a man steeped in senatorial traditions forbids him to attain it. No historian more frequently refutes himself.

Few characters in history have been subject to more divergent opinions than that of the Emperor Tiberius. The view long prevalent has been that his character was largely, if not wholly, bad. This opinion has been chiefly based upon the Tiberian biography in Tacitus' Annals, and to a less extent upon the account of Suetonius and Dio Cassius. Tacitus states that Augustus chose Tiberius as his successor "because he wished, through disparaging comparison with himself, to add to his own glory, and had earlier cast opprobrium upon Tiberius. Suetonius, on the other hand, tells of the high esteem entertained by Augustus for Tiberius, and gives several letters verbatim, wherein is shown an appreciation of Tiberius' worth.

Velleius, while in the service of Tiberius;and therefore perhaps naturally eulogistic, must have had a first-hand knowledge of many of the facts stated,and no adequate reason exists to show that he was not reliable. Tacitus seemed insidiously unfair toward Tiberius. Suetonius wrote many scandalous stories regarding Tiberius and his orgies, indulgences, and sadistic displays. The statements of Suetonius need to be taken with great caution because of his anecdotal, gossipy tendency and carelessness as to sources. Suetonius is a gossip, and speaks ill of every one without any intention of doing harm. Pliny the Elder an ancient author called him tristissimus hominum, "the gloomiest of men".

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|