Roman Amphitheater

The Amphitheater must be regarded as one of the signature public structures of Rome. As far as is known, it was of Roman origin, and reached its highest significance in the imperial period. It is doubtless derived from a doubling of the Greek Theater, which is semi-circular, while the Amphitheater is round or rather oval, which form connects it also with the Circus, whose race-course is rounded at the ends. The Greek Theater had, however, a different purpose : it showed inner conflicts, struggles of the soul, collisions in the ethical world, as we see in Antigone, Oedipus, Prometheus.

The Amphitheater must be regarded as one of the signature public structures of Rome. As far as is known, it was of Roman origin, and reached its highest significance in the imperial period. It is doubtless derived from a doubling of the Greek Theater, which is semi-circular, while the Amphitheater is round or rather oval, which form connects it also with the Circus, whose race-course is rounded at the ends. The Greek Theater had, however, a different purpose : it showed inner conflicts, struggles of the soul, collisions in the ethical world, as we see in Antigone, Oedipus, Prometheus.

But the Roman Amphitheater exhibited literal conflicts of war, involving bloodshed, physical pain and death. From this point of view they were an education in brutality and the whole Roman People received such training from the public purse. All nations were to be subjected and no emotions of pity were to stand in the way of the great world-historical task of Rome. Vae victis ("Woe to the vanquished"0 might be the inscription over every Amphitheater, whose function was to hold up to Rome a picture of herself as imperial conqueror. The Greek Drama had an ideal content and was presented in the Theater, but the Roman Drama had to be realistic and was given in the Amphitheater. No feigned slaying and dying on a stage could be endured by the practical Roman, who was determined to have actual slaughter and death in his dramatic entertainment, even if he sometimes condescends to look at and perchance to imitate a Greek play.

Sometimes there was a fight between lions, or tigers, or elephants, brought from Asia and Africa, but generally gladiators fought the wild beasts. The gladiators were either criminals or captives taken in war, who were compelled to fight for their lives in the arena, or else they were men especially trained for this sort of fighting in schools established for the purpose. Sometimes they succeeded in slaying the wild beast, sometimes they were themselves slain, but however the combat resulted it was always a cruel one. Besides fighting lions and tigers, gladiators sometimes fought with each other till one was killed. Sometimes criminals or Christian martyrs were thrown into the arena to be devoured by wild beasts.

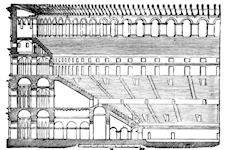

The construction of an Amphitheater was eminently suited for its purpose. It was essentially composed of three parts. First was the arena, the open space at the center where the combats took place, which were of living beings capable of sensation and emotion, and which might be waged between man and man as in the gladiatorial contests, or between man and wild beast, or simply between wild beasts. The oval space was called the arena, from the Latin word for "sand," because it was covered with sand in order that the blood of the victims killed in the combat might be quickly absorbed. Second came the tiers of circular seats facing this central arena, often arranged in radiating wedges from outside inwards. Third was the external wall, the enclosure with its openings and their architectural order and decoration, suggestive of the purpose of the building, and possibly hinting remotely what was going on inside.

The construction of an Amphitheater was eminently suited for its purpose. It was essentially composed of three parts. First was the arena, the open space at the center where the combats took place, which were of living beings capable of sensation and emotion, and which might be waged between man and man as in the gladiatorial contests, or between man and wild beast, or simply between wild beasts. The oval space was called the arena, from the Latin word for "sand," because it was covered with sand in order that the blood of the victims killed in the combat might be quickly absorbed. Second came the tiers of circular seats facing this central arena, often arranged in radiating wedges from outside inwards. Third was the external wall, the enclosure with its openings and their architectural order and decoration, suggestive of the purpose of the building, and possibly hinting remotely what was going on inside.

C. Scribonius Curio commissioned an amphitheater/theater in 50 BC consisting of two wooden halves that revolved. Cicero mentions in passing that in the year 48 BC Curio's amphitheater/theater hybrid was still standing and functional. In BC 46 Caesar built the first true Roman amphitheater (of wood), where he exhibited wild beasts ; and sixteen years later, Taurus built the first one of stone, which, nevertheless, must have been at least partly of wood, since it was destroyed in the great fire during the reign of Nero.

The Theater of Marcellus, of which a considerable portion still stands, forms one of the most characteristic examples of Roman architecture of the best period. This theatre was begun by Julius Cwsar, and finished in the year 11 B.C. by Augustus, who named it after his nephew Marcellus, the son of Octavia. In the llth century, like the Colosseum and the Mausoleum of Hadrian, it was turned into a fortress by the turbulent Roman nobles of the Orsini family. The interior is now occupied by the Palazzo Orsini-Savelli, while the outer arches are used as rag-shops and smithies.

The Piazza di Monte Citorio on the Corso is believed to occupy the site of the Amphitheatre of Statilius Taurus, erected in 31 B.C., the foundations having been found 88 feet below the present surface of the street. At the side of the church of S. Croce in Gerusalemme are considerable remains of the Amphitheatrum Castrense, which was utilised in the construction of the Aurelian Wall, from which it projects, forming a sort of semicircular bastion.

In the same characteristic Roman style as the Theatre of Marcellus, but of a more debased type, is the great Flavian Amphitheatre, built for gladiatorial exhibitions and for the combats of wild beasts, which goes by the name of the Colosseum. Commenced by Vespasian, it M'as dedicated by Titus 80 A.D., and finished by Domitian. It is built in the form of an ellipse, the longer diameter measuring 613 feet and the shorter 510 feet. It rises to a height of 160 feet, covering five acres of ground. In the middle ages it was used as a fortress and afterwards as a quarry; but, though so large a portion has been demolished, it constitutes perhaps the most imposing monument of Roman magnificence which is left.

In the same characteristic Roman style as the Theatre of Marcellus, but of a more debased type, is the great Flavian Amphitheatre, built for gladiatorial exhibitions and for the combats of wild beasts, which goes by the name of the Colosseum. Commenced by Vespasian, it M'as dedicated by Titus 80 A.D., and finished by Domitian. It is built in the form of an ellipse, the longer diameter measuring 613 feet and the shorter 510 feet. It rises to a height of 160 feet, covering five acres of ground. In the middle ages it was used as a fortress and afterwards as a quarry; but, though so large a portion has been demolished, it constitutes perhaps the most imposing monument of Roman magnificence which is left.

The largest building of ancient Rome still standing, the Flavian Amphitheater, was built by the Flavian Emperors (72-82 A. D.), and thus belongs to the epoch of Rome's imperial centralization. Later it shared in the decentralizing tendency of the Empire; the result is, Amphitheaters are found throughout the Roman provinces. In Italy they are at Verona in the North, at Capua and Pompeii in the South. In France there is one at Nimes, in Northern Africa one at El Djem; at Pergamos in Asia Minor and at Trier in Germany are to be seen ruins of Roman Amphitheaters. The dates of these structures are in general uncertain; but there is little doubt that most of them were built after the Colosseum and in imitation of it, both as to purpose and architectural details. Each large town had its own Roman life and showed the same by having an Amphitheater with its bloody sport. Thus each is becoming a Rome in itself, an independent center, which strongly indicates the breaking-up of the Empire through its own inner process. Rome is reproducing herself in the provinces both architecturally and politically, a sign of this in this universal dessemination of the Amphitheater.

It is no wonder that the later Emperors take the seat of Empire away from Rome and locate it in various provincial cities - Milan, Nicomedia and finally in Constantinople. Diocletian would no longer live at Rome, but removed and rebuilt the palace of the Caesars at Spalato in Dalmatia. Constantine, seeing the dissolution of the Western Empire, went to the East and stayed there, reconstructing and concentrating in new forms the Roman Empire of Greece and the Orient, so that it lasted a thousand years longer than imperial Rome of the West. All these facts have their reflection in the architectural monuments of both Empires.

The Roman Colosseum's very magnitude impresses the beholder with the vastness and power of imperial Rome. It seems to hold the whole people for witnessing their own tremendous conflict on the outlying rim of civilization. Estimates differ much in regard to the number of persons the Colosseum is capable of holding: one says 40,000, another 87,000, these seem to be the extremes. At any rate it represents a vast gathering of the' people, not to decide questions of State as under the Republic, but simply to look at themselves imperially. The former might of the People is now concentrated in one man, in one will, and this very Colosseum suggests the fact.

The external Architecture shown in the enclosing wall, is very suggestive. From this wall the three Greek Orders of Architecture look out, not free but engaged, fixed in the rock, held back so to speak from stepping forth into their native independance. Lowest is the Doric Column (here transformed into the Tuscan); in the second story is the Ionic, in the third the Corinthian, each with its entablature running around the entire circuit of the structure. But mark the openings and the entrances in the enclosure are all arched; at least such is the case in the original Flavian building. The Roman would not trust the Greek Architrave for upholding that enormous living mass, the assembled people. He took for use his own Arch which would sustain any burden. Eighty of these arched entrances are in the bottom tier where the multitude could pass in and out under their own architectural form in safety.

No other Roman building shows so mightily the subservient condition of Greek Art and Spirit during the first century of the Empire. These superposed Orders are purely decorative, having no constructive purpose. They show a neglected appearance, there is no fineness of workmanship about them, such as seen in the temples of Greece; even the material does not suit them, the Column presents a cold and cheerless lookin that dull Roman travertine, compared to its happy glistening elegance in Pentelic or Parian marble. Yet what a display of prodigious strength in this act! It is as if a giant had picked up those pretty Greek toys, and placed them upon one another, at the same time fastening them into his huge stone wall to prevent them from tumbling over. The Roman was evidently fond of this superposition of Greek Orders, as it flattered his power in comparison with that of the Greek who never could or would do that. Thus the Colosseum reduced the Greek Column to a mere show alongside the Roman Arch, though this show may be deemed a kind of interpretation, certainly not very brilliant in the present case.

There is a fourth story to the Colosseum which is quite different in character, having rectangular openings and a peristyle encircling the whole structure inside. There seems to be no Arch connected with it outside or inside. It was erected some 150 years after the construction of the first three storys and indicates the reaction toward the Greek world, which was then felt in Rome, and which in less than a hundred years later showed its power in the establishment of the new Greek Empire of the East.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|