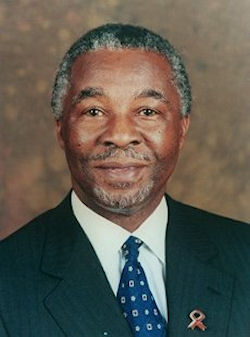

Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki

Mbeki is a short man, with a quiet -- even shy - demeanor. However, an underlying intensity is evident, even on casual acquaintance. Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki was born on 18 June 1942 in Idutywa in the Eastern Cape. Mbeki came from the so-called struggle elite -- a family steeped in the traditions of the African National Congress and anti-apartheid politics. His father was a leading communist Govan Mbeki - a teacher, writer and newspaper publisher. Govan Mbeki, son of a chief who was later deposed by the government, was a warrior - a revolutionary, an educator, a publicist, organiser and leader over many decades. When the limits of peaceful, non-violent struggle were exhausted and the decision taken to continue the political struggle using all means, including armed struggle, Govan became one of the key figures of the underground leadership.

Mbeki is a short man, with a quiet -- even shy - demeanor. However, an underlying intensity is evident, even on casual acquaintance. Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki was born on 18 June 1942 in Idutywa in the Eastern Cape. Mbeki came from the so-called struggle elite -- a family steeped in the traditions of the African National Congress and anti-apartheid politics. His father was a leading communist Govan Mbeki - a teacher, writer and newspaper publisher. Govan Mbeki, son of a chief who was later deposed by the government, was a warrior - a revolutionary, an educator, a publicist, organiser and leader over many decades. When the limits of peaceful, non-violent struggle were exhausted and the decision taken to continue the political struggle using all means, including armed struggle, Govan became one of the key figures of the underground leadership.

After the 1962 arrest of many ANC leaders at Lilliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, Johannesburg, the organization ordered a number of other leaders, including Thabo Mbeki, abroad to set up an opposition-in-exile. When his father was arrested with Mr Mandela, he went to Sussex University in the UK, where he took a Masters degree and left to work in the ANC's London office.

Thabo Mbeki was the consummate diplomat who is believed to be largely responsible for choreographing the overall policy shift in 1990 away from the armed struggle to negotiations. He is rumored to be among the first and most persuasive ANC leaders to argue in favor of suspending armed actions. In making his arguments, Mbeki no doubt had to marshal critical assessments of the efficacy of the armed struggle. Mbeki is said to have a special relationship with ANC President Oliver Tambo, who made Thabo his political secretary in 1978. Mbeki takes a dispassionate, reasoned approach to issues which he presents in understated terms. His authority to deal with white South African officials, captains of industry, white South African opinion leaders, foreign envoys, etc. was second only to Mandela's. When the deputy president travelled abroad without Mbeki, the latter appeared to be in charge of issues relating to negotiations. Mandela would often phone Mbeki from overseas to check on developments.

Mbeki did not devote much of his time to stumping among the black population. He rarely featured at mass rallies and did not attempt to cultivate a constituency in his home area (Transkei) or anywhere else. Some observers believed Mbeki's failure to build grassroots political support damaged his appeal with the masses and could hurt him in his eventual bid for the top job (but others were not convinced).

Self- assured, articulate and charismatic, by 1994 he remained one of the country's shrewdest politicians. He had placed his allies in key government portfolios, and continued to build up and call in favors. Not straitjacketed by ideology, Mbeki is in the same pragmatic camp as Cyril Ramaphosa. If he had a weakness, it was an inability to foresee the harm that association with certain people can cause. After a year in high government office Mbeki remained personally untainted by scandal. Mbeki had always lived comfortably, thanks largely to his wife's income as a United Nations employee and bank official, but never sumptuously. Mbeki had not gained the reputation of a "womanizer".

Mbeki's most important asset was the trust and affection of Nelson Mandela, who made him the Mr. Fix-it of the government and handed him increasing responsibility for the day-to-day administration of the government. If Mandela could, he would install his hand-picked choice for successor in the presidency of both party and country in 1997 and 1999, respectively. However, the gift was not entirely Mandela's to give.

Nelson Mandela stepped down as President of the ANC at the party's national conference in December 1997, when Thabo Mbeki assumed the mantle of leadership. Mbeki won the presidency of South Africa after national elections in 1999, when the ANC won just shy of a two-thirds majority in Parliament. President Mbeki shifted the focus of government from reconciliation to transformation, particularly on the economic front. With political transformation and the foundation of a strong democratic system in place after two free and fair national elections, the ANC recognized the need to focus on bringing economic power to the black majority in South Africa.

In April 2004, the ANC won nearly 70% of the national vote, and Mbeki was reelected for his second 5-year term. In his 2004 State of the Nation address, Mbeki promised his government would reduce poverty, stimulate economic growth, and fight crime. Mbeki said that the government would play a more prominent role in economic development. Mbeki's foreign policy vision saw South Africa deeply involved in continental conflict resolution, peace keeping and reform of regional and continental institutions such as the African Union (AU). His aspiration to see South Africa become a leader of the developing south in its relationship to the industrial north reflects an ANC ideological commitment.

A "cult of personality" consumed the ANC since Mbeki fired Zuma as Deputy President in 2005. Zuma's political allies have alleged that the corruption case is politically-motivated, a charge prosecutors and Mbeki strongly denied. An internal power struggle within the ANC raged since 2005 when President Thabo Mbeki removed Zuma as his deputy after Zuma was implicated in allegations of bribery and corruption associated with a controversial arms deal.

This alienation between Mbeki and Zuma and their respective supporters was further accentuated by broad ANC disaffection resulting from Mbeki's authoritarian leadership style and his efforts to draw a line between the primacy of the party over the state. Many left the ANC because they felt threatened by Mbeki's top down leadership style. Fear accumulated under Mbeki to such an extent that no one spoke out against policies. Everyone was cowed and they allowed even father figures like (Nelson) Mandela to be embarrassed. Mbeki had to be replaced at the 2007 ruling party congress because of the fear he instilled.

Old guard ANC loyalists, and their alliance partners in the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), vehemently objected to Mbeki's belief that the party and the state should remain separate. They preferred the alternative view that the ANC as the majority party had the right to determine state policy, administration, management, and personnel -- in the interest of their constituencies. They also argued vociferously that Mbeki's macro-economic policies, which achieved an average of 4-5 percent annual growth from 2000-2007, were wrong for South Africa and had created a two-tiered economy that made the rich richer and the poor poorer.

The 16-20 December 2007 ANC National Conference in Polokwane, Limpopo significantly shifted power within the ruling party. New ANC President Jacob Zuma defeated incumbent, national President Thabo Mbeki, by a vote of 2,329 to 1,505. Zuma,s allies swept the other top five leadership positions. The Zuma camp also dominated the elections for the ANC,s 86-member National Executive Council (NEC), with sixteen Mbeki Cabinet members (out of 28) losing their NEC seats.

Mbeki's popularity had certainly fallen over the previous couple of years, as evidenced by his loss in Polokwane. But Mbeki had always been careful to ensure that his decisions, especially the more unpopular ones, are taken within the parameters of the law. He also had not been accused of serious misconduct, even by his most vociferous critics.

The ANC's December elections, which saw a dramatic shift in leadership, was mistakenly characterized in some quarters as a radical ideological takeover by the left. Most of the new NEC members had one thing in common: they have been spurned by Mbeki. Some were ANC stalwarts who were never accepted by Mbeki because of lack of formal education (like Enoch Godongwana). Some initially had been part of Mbeki's regime, but were kicked out either under a cloud of suspicion or after being convicted for criminal wrongdoing (like convicted fraudster and former MP Tony Yengeni). Joel Netshitenzhe, one of Mbeki's chief policy advisors, nicknamed the new NEC "the walking wounded." The new NEC also includes the resentful -- powerful provincial elites (like Free State's ANC Chairperson Ace Magashule or Limpopo's ANC Provincial Secretary Cassel Mathale) who had been at odds with Mbeki over his centralized decisions at the provincial and local levels. Mbeki was overthrown by provincial elites, not the left.

Defeated in a bid for a third term as ANC chair in party elections in December 2007, some in the ANC discussed the idea of splitting the ANC and SAG presidencies. However, many in the ANC, in both the Zuma and Mbeki camps, oppose this idea because it would create "two centers of power." The election of Zuma as ANC leader, supported aggressively by the ANC's alliance partners, was followed by a systematic purge of Mbeki's supporters within the Cabinet, the Parliament, the civil services, the provinces and party structures.

High Court Judge Chris Nicholson's ruling on Zuma's appeal in September 2008 was described as a "political Tsunami" that changed South Africa's political culture. It appeared as if Zuma was a victim of a political conspiracy led by Mbeki and the SAG to deny his aspirations to lead the ANC. Zuma supporters seized on Nicholson's views, and immediately began to demand Mbeki's removal. Within ten days, intra-ANC maneuvering resulted in Mbeki being forced to step down just seven months before his second term was to end.

The afternoon of September 20, 2008 African National Congress (ANC) Secretary General Gwede Mantashe, Deputy Secretary General Thandi Modise and ANC Spokesperson Jesse Duarte hosted a press conference on the margins of an emergency meeting of the ANC National Executive Council (NEC) to announced that the NEC has decided by consensus to recall Thabo Mbeki as President of South Africa. Mantashe said that after meeting late into the night, the senior leaders of the ANC reached this consensus decision to "bring the party together," "unite the party" around key issues, and to search for "certainty and stability" in the leadership of the ANC. When asked by a reporter what if Mr. Mbeki objected and refused to step down, Mantashe articulated the ANC's tradition of party discipline, noting that Mbeki was a deployee of the ANC, one who accepted his deployment as "an act of mutual respect and commitment to the Movement;" and disciplined deployees "will take the directives of the Movement seriously." The forced resignation of Mbeki in September 2008 led to ultimate victory for Zuma's faction within the ANC, all but guaranteeing Zuma's rise to be the next President of the Republic.

The African Union’s (AU) High Level Panel on Darfur, led by former President Thabo Mbeki of South Africa, was convened in 2009 to examine the situation in Darfur and to come up with recommendations to address issues of accountability, combating impunity, and bringing about healing and reconciliation for the people of Darfur.

Personal | |

| |

Positions last held in government | |

| |

Academic Qualifications | |

| |

Career/Positions/Memberships/Other Activities | |

| |

Positions last held/Career/Memberships/Other Activities | |

| |

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|