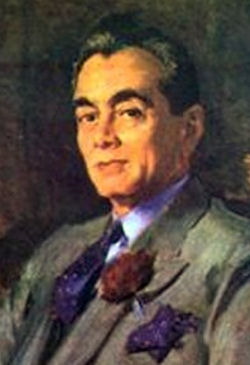

Manuel Luis Quezon Antonio y Molina

Manuel Luis Quezon Antonio y Molina, a member of the Partido Nacionalista, served as a Resident Commissioner from the Philippines from 1909 to 1916. He later served as president of the territorial senate and president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines. Ambitious and powerful, Quezon had served as governor in the provinces before winning election as floor leader in the Philippine assembly. uring a career that spanned the length of America’s colonial rule in the Philippines, Manuel L. Quezon held an unrivaled grasp upon territorial politics that culminated with his service as the commonwealth’s first president. Although he once fought against the United States during its invasion of the islands in the early 1900s, Quezon quickly catapulted himself into a Resident Commissioner seat by the sheer force of his personality and natural political savvy. Young and brilliant, Quezon, according to a political rival, possessed “an ability and persistence rare and creditable to any representative in any parliament in the world.

Manuel Luis Quezon Antonio y Molina, a member of the Partido Nacionalista, served as a Resident Commissioner from the Philippines from 1909 to 1916. He later served as president of the territorial senate and president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines. Ambitious and powerful, Quezon had served as governor in the provinces before winning election as floor leader in the Philippine assembly. uring a career that spanned the length of America’s colonial rule in the Philippines, Manuel L. Quezon held an unrivaled grasp upon territorial politics that culminated with his service as the commonwealth’s first president. Although he once fought against the United States during its invasion of the islands in the early 1900s, Quezon quickly catapulted himself into a Resident Commissioner seat by the sheer force of his personality and natural political savvy. Young and brilliant, Quezon, according to a political rival, possessed “an ability and persistence rare and creditable to any representative in any parliament in the world.

Manuel Luis Quezon was born on August 19, 1878, in Baler, a town on the island of Luzon in Tayabas Province, Philippines, to Lucio, a veteran of the Spanish Army and a small-business owner, and Maria Molina Quezon. The family lived in the remote “mountainous, typhoon plagued” swath of the province that hugged much of the eastern coastline of Luzon. Quezon’s parents eventually became schoolteachers, which allowed the family to live comfortably in Baler. Manuel, the eldest of three sons, and his brothers, Pedro and Teodorico, were taught at home by a local parish priest. In 1888 Quezon left Baler to attend Colegio de San Juan de Letran in Manila, graduating in 1894. Shortly after, he matriculated to the University of Santo Tomas, also in Manila, to study law.

About a year later, however, Quezon left school and returned home during the Philippines’ revolution against Spain. He resumed his studies in 1897, but when hostilities began between the United States and the Philippines in February 1899, Quezon joined General Emilio Aguinaldo’s forces. Commissioned as a second lieutenant, he saw little action, but rose to captain and served on Aguinaldo’s staff. After surrendering to U.S. forces in 1901, Quezon spent six hard months in prison, where he contracted malaria and tuberculosis. He suffered from complications of the diseases for the rest of his life.

On his release, Quezon resumed his legal studies at Santo Tomas and earned a bachelor of laws degree in 1903 before returning to his home province. Only in his mid20s, intelligent, and a natural “master of political intrigue,” Quezon caught the attention of American administrators, particularly Harry H. Bandholtz, the director of the local constabulary, and district judge Paul Linebarger. The two Americans soon adopted Quezon as a protégé.

As a result, Quezon routinely walked a fine line, balancing the colonial agenda of his powerful American associates, the interests of Philippine nationalists, and his own career ambitions. According to a recent study by Alfred W. McCoy, a leading historian of the Philippines, Quezon — in an arrangement that seemed equal parts quid pro quo and extortion — worked as an informant for American security officials who kept a detailed list of accusations against Quezon — ranging from corruption to murder — that they could use to destroy Quezon if he ever ceased being “a loyal constabulary asset,” McCoy wrote.

Quezon’s political career began in 1903, when Linebarger named him the provincial attorney, or fiscal, of Mindoro, an island province near Tayabas. Quezon was quickly promoted to serve as fiscal of his home province, where he famously prosecuted Francis J. Berry, who owned the Cablenews-American, one of the largest daily newspapers in the Philippines, on charges of illegal land transactions. He won the case, but had to defend himself against charges of corruption by Berry’s allies. Once the dust settled, Quezon resigned and returned to private practice.

In 1906 Quezon ran for governor of Tayabas Province, campaigning not only on his reputation as a lawyer, but on his connections with Bandholtz and other American officials. Belying his inexperience — he had been in politics less than two year s— Quezon deftly maneuvered past two other candidates and overcame shifting alliances to win his seat.

In 1907 the Philippines began sending two Resident Commissioners to the U.S. Congress to lobby on behalf of the territory’s interests. The assembly and the commission selected one candidate each, which the opposite chamber then had to ratify. It is not entirely clear why Quezon wanted the position in Washington — one biographer has conjectured that Quezon wanted to be the hero who brought independence to the Philippines — but in 1909 he sought the Resident Commissioner seat occupied by Nacionalista Pablo Ocampo. 8 Quezon won handily with 61 of the 71 available votes. Already fluent in Spanish, Tagalog, and the local dialects in Tayabas, Quezon recalled the “most serious obstacle to the performance of my duties in Washington was my very limited knowledge of the English language.”

Almost to a man, the Philippines’ 13 Resident Commissioners — the islands’ representatives in Washington who initially served in pairs — lobbied for beneficial tariff rates and more territorial autonomy. With the new tariffs in place after 1909, Congress’s dealings with the Philippines switched gears, and with the new Resident Commissioner, Manuel Quezon, taking the lead, debate began focusing more and more on the islands’ long-term political future. Beginning with the 62nd Congress, Quezon received help from a new House majority after Democrats took back the chamber for the first time in 15 years.

For decades — well before Congress ever became involved in the Philippines — independence had been the ultimate goal for the islands’ leaders, and for the vast majority of the people there, Philippine nationalism was the going intellectual currency. Gradually, behind the efforts of Resident Commissioners like Manuel L. Quezon, Jaime C. de Veyra, and Pedro Guevara, they chipped away at American authority in the Philippines. But timing was everything: win independence too quickly and the Philippines might flounder; pursue it too slowly and the Philippines might never get out from under America’s shadow.

Quezon played a major role in obtaining Congress’ passage in 1916 of the Jones Act, which pledged independence for the Philippines without giving a specific date when it would take effect. The act gave the Philippines greater autonomy and provided for the creation of a bicameral national legislature modeled after the U.S. Congress. Quezon resigned as commissioner and returned to Manila to be elected to the newly formed Philippine Senate in 1916; he subsequently served as its president until 1935. In 1922 he gained control of the Nacionalista Party, which had previously been led by his rival Sergio Osmeña.

Finally, in 1934 Congress and the territorial legislature approved the Philippine Independence Act (the Tydings– McDuffie Act), authorizing the creation of a new Philippine constitution. Quezon won election as the first president of the Philippines in 1935. Throughout his postcongressional tenure, Quezon held near-dictatorial sway over the Partido Nacionalista, either personally selecting or approving each of the next nine Philippine Resident Commissioners. He leveraged the Resident Commissioner position as a means to solidify his support in Manila, enabling him to virtually exile political opponents. On the other hand, if an ally broke ranks with him on the Hill, Quezon was quick to name a replacement. As president in the 1930s, Quezon worked to strengthen his authority at home and tried to brace the nation for war as Japan began encroaching on the islands.

John Gunther’s Inside Asia (1938-39 edition) noted: "Elastic, electric, Manuel Quezon is a sort of Beau Brummel among dictators. Here is an extraordinarily engaging little man. The prankishness of Quezon, the rakish tilt to the brim of his hat, his love for the lights of pleasure as well as the light of power, his dash and roguery, the spirited elegance of his establishments all the way from the yacht cruising on Manila Bay to the refulgent pearls – so luminous they seem – cruising on his shirtfront , combine brightly to indicate a character straight off Broadway or Piccadilly Circus, a lighthearted playboy among eastern statesmen.... He is one of the world’s best ballroom dancers; also one of the world’s supplest and hardest-boiled practical politicians. He loves cards and alcohol; also he loves his country and his career. He likes to laugh – even at himself-but he is a genuine revolutionary, as much the father of his country as Kamal Ataturk. The history of the Philippine Islands in the twentieth century and the biography of Manuel Quezon are indissolubly one."

Japan’s decision to attack the Philippines was part of a larger strategy to seize oil reserves in the Dutch East Indies. To do so, however, Japan needed to eliminate the U.S. forces based in the Philippines. Japan’s relentless bombing campaign quickly overwhelmed the Philippines. The U.S. Navy withdrew, enabling Japanese forces to land on separate sides of Luzon. As Japanese troops marched toward Manila, U.S. and Filipino forces evacuated to the Bataan Peninsula while MacArthur removed his staff and the commonwealth government to the harbor fortress on Corregidor Island. President Quezon scrambled to keep the Philippines out of the conflict and pushed FDR to work out a deal with Japan that, among other things, would grant the islands immediate independence, establish guaranteed neutrality, demilitarize the archipelago, and enact new trade agreements with Japan and the United States. Roosevelt flatly denied Quezon’s request.

Hoping to negotiate with Japan directly, Quezon, whose health was deteriorating, pushed Congress to advance the date for independence. There was a widespread belief in the Philippines, which Quezon shared, that Japan’s successful invasion stemmed directly from America’s failure to fortify the territory’s defenses. Complicating that sentiment was Japan’s tactic to appeal to Filipinos on racial grounds: “Like it or not, you are Filipinos and belong to the Oriental race,” read propaganda leaflets. “No matter how hard you try, you cannot become white people.""

At the urging of the Americans, Quezon’s government-in-exile moved from Australia to the United States. With no need for an official go-between, FDR agreed to suspend the office of the high commissioner, in theory, strengthening Quezon’s hand. But with no country to govern, the government-in-exile primarily handled ceremonial events. Quezon served as a member of the Pacific War Council, signed the declaration of the United Nations against the Fascist nations, and wrote his autobiography, The Good Fight (1946). He lived in Saranac Lake in Upstate New York as his health started to fail. Quezon died on August 1, 1944, succumbing to the longterm effects of his battle with tuberculosis. In his honor, an outlying suburb of Manila was named Quezon City and became the site of the national capital of the Philippines.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|