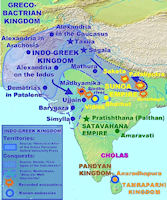

Indo-Greek Kingdom - 205 BC - 10 AD

Founded by the former Graeco-Bactrian king Demetrius I (ruled: ?205-171 BC ), who first invaded India in 180 BC, the Indo-Greek Kingdom comprised a number of dynasties, polities and petty kingships in the Hindu Kush, Gandhara (northeastern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan) and northern India.

By the time of Demetrios (205) the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom comprised even the country beyond the Jhelum. His successor, Eukratides, struck coins with Greek and Indian inscriptions. Menander [r. 155-130 BC] succeeded Demetrius, and extended his conquests to Serica; but over these territories his sway was transient. The new Greek kingdom extended itself to the South and East. Presently the Parthians grew stronger and seized most of Bactria, so making a great barrier between the eastern and western Hellenism of Asia. Though the western provinces of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom became soon afterwards a prey to Parthian conquests, it increased in the East, up to the Jumna and embraced even Gujarat.

During their two centuries of rule, the Indo-Greek kings combined Greek and Indian languages and symbols on their coins and blended Greek, Hindu and Buddhist religious practices, as revealed in the archaeological remains of their cities and in their support of Buddhism. The Indo-Greek kings melded the disparate cultures of Greece and India to a unique artform, cultural, the consequences of which were felt for centuries through the diffusion of Graeco-Buddhist and Gandharan sculpture, painting and architecture.

The Indo-Greeks shown brightly for several generations, then disappeared as a political entity seemingly overnight, around 10 AD, following the invasions of the Indo-Scythians, although pockets of Greek populations probably remained for several centuries longer under the subsequent rule of the Indo-Parthians and Kushans.

This Graeco-Indian kingdom, which lasted through the second century B.c., was the kingdom which seems to have influenced India far more than the earlier Graeco-Bactrian monarchy. The existence of both, asserted by Strabo and Justin, has of recent years been further established by the discovery of a vast number of coins, purely Greek in the case of Diodotus, Euthydemus, and the earlier sovrans, and of the best workmanship, then gradually debased in artistic value, adopting Indian script beside the Greek, and finally lapsing back again into purely oriental work. These coins have excited the liveliest interest, and able numismatists have sought to reconstitute the proper series and the relations of the many kings—at least twelve are known —from the workmanship and the titles on these medals.

Some time after the seventh century the Brahmans began to foretell the fortunes of children from the position of the stars of their parents, to look for the marks of good and bad fortune on the human body as well as in the sky, and to question the stars about the favourable hours for the transactions or festivals of the house, and the labours of the field, voyages and travels. Though the book of the law declares astrology to be a wicked occupation,2 it was carried on to a considerable extent in the fifth and fourth centuries. But this astrological superstition has nevertheless remained without effect in advancing the astronomy of the Brahmans; further advance was due to the foreign help gained by closer contact with the kingdom of the Seleucids, and the influence of the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom, which extended its power to the east beyond the Indus, and the Graeco-Indian kingdom which succeeded it in the second century.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|