Mongolia - Economy

, Mongolia was the world's fastest-growing economy in 2012, logging a GDP increase of 12.3 percent. What fueled the boom was first and foremost foreign direct investment, peaking at around $5 billion (4.4 billion euros) - before dropping to zero in 2015. That's because of the freefall in commodity prices globally which has also meant a dramatic loss of jobs in the Asian country neighboring China. Unemployment in Mongolia reaches nearly 12 percent this year, compared with just 5 percent recorded in 2012. Gross domestic product slowed to 2.3 percent last year, the weakest pace since 2009, with analysts predicting growth to come in at just 0.8 percent in 2016.

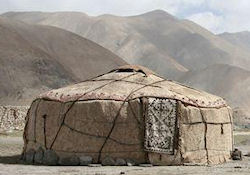

Gers [yurts] remain the most common type of housing in Mongolia. Data from 2002-2003 shows that 45 percent of citizens lived in gers, one-third in conventional houses and one-fifth in apartments. The large peri-urban “ger” (the traditional felt yurt of the Mongolian herders) districts that surround Ulaanbaatar now provide accommodation for around 60 percent of the urban population.

, Mongolia was the world's fastest-growing economy in 2012, logging a GDP increase of 12.3 percent. What fueled the boom was first and foremost foreign direct investment, peaking at around $5 billion (4.4 billion euros) - before dropping to zero in 2015. That's because of the freefall in commodity prices globally which has also meant a dramatic loss of jobs in the Asian country neighboring China. Unemployment in Mongolia reaches nearly 12 percent this year, compared with just 5 percent recorded in 2012. Gross domestic product slowed to 2.3 percent last year, the weakest pace since 2009, with analysts predicting growth to come in at just 0.8 percent in 2016.

Gers [yurts] remain the most common type of housing in Mongolia. Data from 2002-2003 shows that 45 percent of citizens lived in gers, one-third in conventional houses and one-fifth in apartments. The large peri-urban “ger” (the traditional felt yurt of the Mongolian herders) districts that surround Ulaanbaatar now provide accommodation for around 60 percent of the urban population.

Per capita income remains below 1990 levels. Though a large majority of Mongolia’s working age population is educated and literate, there are relatively few opportunities for skilled labor. Livestock herding, the informal sector, and, increasingly, mining account for large percentages of jobs created since 1990, but provide relatively few highly skilled positions.

Economic and social disparity between urban centers and the rest of the country isalso a cause for concern. Residents of Ulaanbaatar in particular have far moreeconomic opportunity, social services, and access to information as well as linksto the outside world. As many as one million people, nearly 40 percent of thecountry’s population, reside in the bustling capital city. Ulaanbaatar’s traffic jams,building construction, internet cafes, universities and a booming informal sector provide a stark contrast to typical provincial capitals (“aimag” centers) and rural towns, and to the everyday life of Mongolia’s many livestock herders.

The 2007/2008 Global Human Development Report indicates that Mongolia’s international ranking in terms of HDI was 114 out of 177 countries. Mongolia’s relatively low global ranking in HDI is primarily due to its low per capita GDP. Mongolian per capita GDP was US $2,107. In the decade up to 2010, real income per capita in Mongolia more than doubled, but still remains about one-tenth of the global average. The population percentage living under the national poverty line was 32.2 percent in 2006. Distance from markets, lack of infrastructure, and limited opportunities to access education, healthcare and information, and the resulting unavailability of jobs all have negative impacts on rural living standards.

The mining sector is a major contributor to Mongolia’s economy and its importance is expected to grow in the future. During 2007, the mining sector accounted for 27.5 percent of GDP and 86.1 percent of export earnings. Mongolia is rich in minerals, the most significant being copper, zinc, gold and coal. The rapid increase in exploration and development activities in the last decade gives a promising outlook for continued strong growth for this sector in the foreseeable future. Exploration activities have resulted in the discovery of a pipeline of potential mineral project developments that include Oyu Tolgoi (copper and gold), Tavan Tolgoi (coal), Tsagaan Suvraga (copper and molybdenum), and Tumurtei (iron ore).

Mongolian officials appear to prefer a "third-neighbor" policy in the mining sector. Western firms are preferred as strategic partners, but that Chinese and Russian partners are necessary for transportation. Tavan Tolgoi, located 342 miles from the Mongolian capital, is one of the world's 10 biggest coal deposits (6.5 billion tons). Oyu Tolgoi (32 million tons of copper and 32 million oz of gold) is located in the south Gobi region 342 miles south of Ulan Bator and 50 miles north of the Chinese-Mongolian border.

In the 2008 Mongolia appeared just steps away from becoming a global mining giant. Copper prices were at record highs, Mongolia's premiere Erdenet copper mine could not sell its product fast enough to China, and the GOM had a surplus of nearly USD 1 billion. Giant firms such as Rio Tinto, Peabody Energy, BHP Billiton, Areva, Xstrata, and CVRD, were constantly knocking at Mongolia's door. The standard argument went that Mongolia was sitting on fabulous, un-tapped copper, gold, coal, molybdenum, zinc, and uranium deposits, and because prices were high and likely to stay there because of ever buoyant China. Of course, prices for copper tanked.

On 02 March 2009, the Mongolian National Security Council voted 2 to 1 to approve the long-delayed investment agreement for the Oyu Tolgoi copper-gold project in Mongolia's South Gobi desert region. An Oyu Tolgoi (OT) agreement was a long time coming. Initial attempts to stabilize formally the legal and regulatory framework for this USD 7 billion project began in 2004, but ran afoul of Mongolian election year politics. At that time, Canadian exploration company Ivanhoe Mines held the mining license rights and had been lobbying the senior Mongolian leadership of the ruling Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party (MPRP), led by then-PM and later President Enkhbayar. Ivanhoe's chief legal counsel, John Fognani, explained that the leadership had been extremely encouraging, going so far as to "promise" that they would conclude the deal on its own initiative. Top MPRP leaders asserted that the PM had the power to force an agreement on Mongolia -- regardless of any legal or regulatory requirement to consult with Parliament or the public. Fognani explained that the business community believed a narrow band of post-socialist barons led by Enkhbayar could do what they wanted; and so, businesses had only to deal with them. However, Mongolia had become a functioning democracy by the mid-1990s, and the impact of the vote and a constitution that vested power in Parliament had begun to limit what the socialist era barons could force down the throats of the public or Parliament.

In summer 2009 the government negotiated an “Investment Agreement” with Rio Tinto and Ivanhoe Mines to develop the Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold deposit. On August 25, 2009, parliament passed four laws--one repealing the windfall profits tax, one adjusting corporate tax structures to accommodate large-scale projects, and two involving infrastructure--necessary to allow the signing of the deal. The deal was concluded in a gala signing ceremony on October 6, 2009, and the agreement went into full legal force 6 months later, on April 6, 2010. Although certain parliamentarians called for elements of the agreement to be renegotiated in late 2011, the Mongolian Government stood by the original investment agreement.

A few Mongolian officials claim that Mongolia's coal deposits stretch west to east in an unbroken (and unsubstantiated) 170-billion ton belt of untapped hydrocarbon wonder. However, Western firms actively prospecting for both thermal and coking coal argue that Mongolia's coal reserves, while respectable, are deposed in discrete basins rather than a titanic belt. But there are some major nuggets among these deposits, such as the exceedingly fine and well-situated six billion ton coking and thermal coal Tavan Tolgoi (TT) deposit near the Mongolia-China border, for example. Moreover, no matter the size of the deposits, companies warn that coal is only valuable if, and only if, it can be brought to a market economically, which in Mongolia's case must be China.Mongolian coal offsets demand elsewhere in China and Asia, making it a very fungible asset. However, hard-nosed questions about the nature, quality, size, and marketability of Mongolia's deposits remain unanswered.

Mongolia lacks the capacity to design and implement the policies and programs necessary to achieve sustainable economic growth. Specifically, Mongolia lacks western-educated, apolitical, well-paid, private and public sector professionals who are able to grasp the principles of and implement private sector-led growth and rule of law, the two determinants of sustainable economic growth. This lack of capable manpower is probably the single, largest obstacle to Mongolia's ability to move forward.

Economic activity in Mongolia has traditionally been based on herding and agriculture, although development of extensive mineral deposits of copper, coal, molybdenum, tin, tungsten, and gold have emerged as a driver of industrial production. Soviet assistance, at its height one-third of GDP, disappeared almost overnight in 1990-91 at the time of the dismantlement of the U.S.S.R., leading to a very deep recession. Economic growth returned due to reform embracing free-market economics and extensive privatization of the formerly state-run economy. Severe winters and summer droughts in 2000-2001 and 2001-2002 resulted in massive livestock die-off and anemic GDP growth of 1.1% in 2000 and 1% in 2001. This was compounded by falling prices for Mongolia's primary-sector exports and widespread opposition to privatization.

Growth improved to 4% in 2002, 5% in 2003, 10.6% in 2004, 6.2% in 2005, and 7.5% in 2006. Because of a boom in the mining sector, Mongolia had high growth rates in 2007 and 2008 (9.9% and 8.9%, respectively). Due to the severe 2009-2010 winter, Mongolia lost 9.7 million animals, or 22% of total livestock. This immediately affected meat prices, which increased twofold; GDP dropped 1.6% in 2009. Growth began anew in 2010, with GDP increasing 25.3% over 2009 as Mongolia emerged from the economic crisis. GDP growth in 2011 was expected to reach 16.4%. However, inflation continued to erode GDP gains, with an average rate of 12.6% expected in Mongolia at the end of 2011 and higher rates anticipated in 2012 as the government increases transfer and spending programs prior to the June 2012 parliamentary elections.

Besides mining (21.8% of GDP) and agriculture (16% of GDP), dominant industries in the composition of GDP are wholesale and retail trade and service, transportation and storage, and real estate activities. Mongolia's economy continues to be heavily influenced by its neighbors. For example, Mongolia purchases nearly all of its petroleum products from Russia.

China is Mongolia's chief export partner. Mongolia, which joined the World Trade Organization in 1997, is the only member of that organization to not be a participant in a regional trade organization. Mongolia seeks to expand its participation and integration into Asian regional economic and trade regimes.

Because of Mongolia's remoteness and natural beauty, the tourism sector offers potential for growth. Prior to the onset of the global economic crisis, spiking international commodity prices led to a surge of international interest in investing in Mongolia's minerals sector despite the absence of a policy environment firmly conducive to private investment; the end of the crisis brought a return of the attention of foreign investors. How effectively Mongolia mobilizes private international investment around its comparative advantages (mineral wealth, small population, and proximity to China and its burgeoning markets) will ultimately determine its success in sustaining rapid economic growth. Tax reforms enacted on January 1, 2007 and other mining policies helped government revenues jump 33% in 2007. Meanwhile, major amendments to the minerals law allowed the government to take an equity stake in major new mines.

Major development slowed in late 2007 and early 2008 as Mongolia's parliament proved unwilling to move on major deals and declined to reform mining laws that observers said substantially varied from best practices. This frustrated many foreign and domestic investors and others who hoped to see Mongolia's promising mining sector grow rapidly. In 2009, sharp drops in commodity prices and the effects of the global financial crisis began to be felt in Mongolia's economy.

The local currency dropped some 40% against the U.S. dollar, and two of the 16 commercial banks were taken into receivership, but a series of quick and effective moves, including a Stand-By Arrangement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), helped maintain stability and kicked off a broad discussion on fiscal and financial reforms. That program concluded successfully in late 2010, but both the IMF and World Bank later criticized Mongolia for returning to potentially dangerous pro-cyclical policies in 2011, with fiscal spending likely to rise prior to the 2012 elections.

The Parliament of Mongolia finally considered and adopted the Law on the Regulation of Foreign Investment in Entities Operating in Strategic Sectors on 17 May 2012 after three years it had been submitted by the Members of Parliament. The ultimate goal of the Law is to ensure orderly operations of foreign investment in the country in relation to national economy and security interests. MP and Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade G.Zandanshatar, one of the initiators of the Law said that this does not mean pushing away foreign investors. The legal environment is being created for foreign investors to get permission from the Government while operating in Mongolia.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|