Manchuria Geography

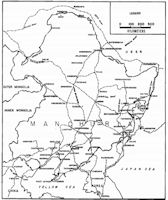

Militarily, the key to Manchuria is the central valley region. With its high population densities, its agricultural and industrial value, and its strategic position, control of the valley means control of Manchuria as a whole. Thus, defense of the central valley is a critical issue for any occupying power. In order to control any central valley, an occupying force must deny enemy access to the area by establishing adequate defenses in mountainous regions surrounding the central valley and by controlling potential avenues of approach.

The Grand Khingans could be crossed to the south through a number of narrow passes, but a force crossing these passes must first cross hundreds of kilometers of trackless desert waste. The actual height and slopes of the Grand Khingans do not prohibit military operations by mechanized forces. The major limiting factors are absence of good roads, lack of water, and rough terrain, which inhibits rapid movement. Two potential avenues of approach traverse the Lesser Khingans. The first, south and southwest from Sunwu, involves crossing hilly, wooded terrain on poor roads. The second, along the Sungari River by way of Chiamussu, involves mastery of swamplands, also traversed by poor roads. The Su'n'gari River, however, offers an excellent arena for amphibious advance.

Eastern Manchuria offers a variety of avenues of approach, none particularly good. The better avenues follow the rail lines, rivers, or major roads of the region. The Iman-Hutou-Mishan axis is limited by marshlands, which are virtually inundated in the rainy months of July and August. The roads into eastern Manchuria south of Lake Khanka by way of Suifenho and Tungning offer restricted corridors of advance across hilly, brushy terrain. The roads themselves lack hard surfaces. In the southeast a force could advance along the Tumen River by way of Hungchun, Tumen, Yenchi, or Tunhoa, but as in other areas, the advance would be hindered by water obstacles, bottlenecks, and poor roads. In view of the paucity of good avenues of approach through the barrier mountains into central Manchuria, any military force would have to rely on its imagination and resourcefulness to create avenues either by overcoming terrain obstacles or by mastering the problems of operations in remote regions.

Manchuria is comparable in size to Western Europe, from the Pyrenees to the Elbe. Manchuria covers 1.5 million square kilometers bounded on the south by Korea, the Liaotung Gulf, and China, on the east and north by the Soviet Far Eastern province and Siberia, and on the west by Outer Mongolia and Inner Mongolia. By virtue of its geographic location, its natural resources, and its population, Manchuria is an area of considerable strategic value. Its fertile central regions are both industrially and agriculturally important. Its geographical location gives to it a dominant position vis-a-vis China and the Soviet Far East. For this reason, the major powers of the region, China, Russia, and Japan, had long sought possession of Manchuria.

Because of its large size and its geographical and climatic diversity, Manchuria can best be described as a series of concentric circles. The inner circle contains the heartland of Manchuria, the large central valley. Around the valley runs another large circle of mountains of various size and ruggedness, protecting the central valley from the west, north, east, and southeast. To the south, this circle opens onto the Liaotung Gulf. Beyond this circle of mountains is a peripheral area abutting Mongolia, Siberia, and the Soviet Far East.

The central valley of Manchuria, containing the basins of the Liao, Sungari, Nen, Hsiliao, Choerh, and other rivers, extends 1,000 kilometers from north to south and 400 to 500 kilometers from east to west. In 1945 a well-developed road and rail network traversed the region, connecting the major industrial cities of Mukden, Changchun, Harbin, and Tsitsihar. Terrain in the central valley is generally flat, and cultivated areas predominate.

West of the central valley is the Grand Khingan mountain range. Running from north to south, this range extends from the Amur River region of northern Manchuria southward to a junction with the mountains of northern China. The mountains vary in height from 1,800 meters in the north, to 1,500 meters in the central region, and finally to 1,900 meters in the south. From the west the mountains rise less steeply than from the east. Land west of the mountains averages from 1,000 to 1,200 meters in altitude, thus the mountains rise from 300 to 900 meters. Land east of the mountains averages from 500 to 700 meters, thus the mountains loom at greater heights. The Grand Khingans form a belt of dissected mountains and broad swampy valleys varying in width from 500 kilometers in the north to eighty kilometers in the south. The mountains are heavily forested in the north, but these forests decrease in density to the south, finally giving way to brush and scrub grass. Of several passes and narrow valleys that traverse the Grand Khingans, in 1945 the two principal passes contained the railroad lines from Yakoshih to Pokotu and from Halung-Arshaan to Solun. Poor roads paralleled these rail lines, and elsewhere numerous pack and cart trails traversed the mountain range.

Bounding the northern portion of the central valley of Manchuria, the Lesser Khingan Mountains extend from northwest to southeast for a distance of 600 kilometers, with an average width from 100 to 300 kilometers. These mountains, a series of heavily wooded rounded hills, conical summits, and open valleys, range in elevation from 700 to 1,300 meters. In 1945, the main passages through the mountains contained the rail lines from Tsitsihar and Harbin to Aihun on the Amur River.

East of the central valley are the Eastern Highlands, extending for 1,500 kilometers from the Liaotung Peninsula in the south to the junction of the Amur and Ussuri rivers. These highlands, at places almost 350 kilometers wide, separate the Central Lowlands from the Soviet Far Eastern provinces. In the south, the Tunghua Mountains average 500 to 1,300 meters in elevation. Farther to the north near Mutanchiang, elevations run from 900 to 1,500 meters, while south of the Sungari River elevations average 700 to 1,000 meters. In 1945, rail lines and roads traversed the Eastern Highlands from Changchun via Kirin to Tumen; from Harbin via Mutanchiang to Ussurysk; and from Harbin via Mutanchiang and Mishan to Iman on the Ussuri River. Less important military railroad lines ran from Tungning to W angching and parallel to the Soviet border from Liaoheishan to Suiyang.

Heavy forests cover the Eastern Manchurian Highlands in the south, and dense thickets of small trees and brush cover the central and northern portions. The valley of the Sungari River, running northeast from Harbin to Chiamussu, separates the Eastern Hig·hlands and Lesser Khingan Mountains. Before 1945, the Japanese built several military roads through the Eastern Highlands to provide communications between adjacent units and rear installations.

Beyond the circle of mountains encasing the central valley are regions on the periphery of Manchuria. In the west the deserts of Inner Mongolia extend from the Grand Khingan Mountains to the Outer Mongolian border, and the Barga Plateau stretches from the northern Grand Khingans to Mongolia and the Argun river border between Manchuria and Siberia. Northeast and east of the Eastern Highlands are marshy lowlands along the Ussuri River and at the junction of the Ussuri, Amur, and Sungari rivers.

The arid deserts of Inner Mongolia (the Dalai Plateau, an eastern extension of the Gobi Desert) extend west from the Grand Khingan Mountains into Mongolia. The distance from the mountains to the Mongolian border varies from 200 kilometers in the north to 400 kilometers in the south (the Linhsi area). This region of high plateau (1,000 to 1,200 meters) contains numerous sand dunes, some small hills of 100 to 150 meters, dry stream beds, and occasional saline lakes. Water is in scarce supply. Farther to the north, the Barga Plateau stretches west of the Grand Khingans from the Yakoshih area to the Argun River and the Soviet Outer Mongolian border.

Sand dunes, numerous shallow depressions, and wide rock mesas make up the plateau of 600 to 800 meters, with isolated hills rising an additional 200 meters. The Hailar River meanders from east to west across the plateau, and in the west are two large saline lakes, the Dali Nuur and the Buyr Nuur. Numerous small tracks, but no hard-surfaced roads, traversed the Dalai Plateau in 1945. Running from Manchouli in northwest Manchuria to the Grand Khingan mountain passes at Y akoshih, the historic singletrack Chinese Eastern Railroad bisected the Barga Plateau. A third class road paralleled the railroad, and other similar roads radiated from north and south of Hailar.

In northeastern Manchuria a vast, flat, marshy lowland averaging thirty to 100 meters in elevation covers the region where the Amur, Ussuri, and Sungari rivers converge. The Sungari River cuts through the region from southwest to northeast. The flat, undulating region contains the Sungari River valley proper (thirty-five kilometers wide) and occasional hills. The lowland extends across the Amur River into Siberia. The entire region is swampy and usually flooded during the months of July and August. At the time of the 1945 campaign, overland routes consisted of third and fourth rate roads and trails, the most important of which extended from the Amur River at Lopei and Tungchiang along both banks of the Sungari to the city of Chiamussu.

Climatic differences parallel geographic differences: the more temperate coastal area clashes with the extreme temperature and rainfall ranges of the interior. In the 1nterior, winter brings extremely low temperatures. Temperatures decrease to the west of the Grand Khingan Mountains. Also, the interior generally lacks rainfall in winter. Summer is the season of heavy rains in most of Manchuria. The monsoon drift of moist warm maritime air from the southeast crosses central Manchuria, bringing with it widespread low overcasts and heavy rains. Most of the year's precipitation occurs during July and August. Rainfall is heaviest in the east, while the summer months also bring rains as far west as the Grand Khingan Mountains and the Barga Plateau. The highest temperatures are in July and August with the severest temperatures recorded in the desert regions of the west.

Spring and fall are transitional periods with limited rainfall and moderate temperatures. Autumn (September to November) is the best season for military operations. Heavy rains stop, temperatures moderate. and high winds and dust storms subside.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|