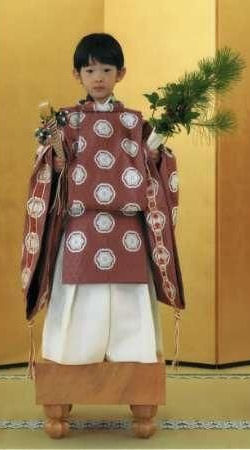

Prince Hisahito

Japan's long wait for a male successor to the Chrysanthemum throne came to an end early on the morning of 06 September 2006, as Princess Kiko gave birth to the Imperial family's first male heir in 41 years. His birth seemed likely to bring an end to any remaining debate on revising Japan's Imperial Household Law to allow females and matrilineal descendants to ascend the throne. Public reaction was overwhelmingly positive, notwithstanding some sniping about the costs of supporting the royal family in the media.

Japan's long wait for a male successor to the Chrysanthemum throne came to an end early on the morning of 06 September 2006, as Princess Kiko gave birth to the Imperial family's first male heir in 41 years. His birth seemed likely to bring an end to any remaining debate on revising Japan's Imperial Household Law to allow females and matrilineal descendants to ascend the throne. Public reaction was overwhelmingly positive, notwithstanding some sniping about the costs of supporting the royal family in the media.

Japan's Princess Kiko, wife of the Emperor's second son, gave birth to a boy on 06 September 2006, the first male heir to the Imperial throne born to the Emperor's immediate family since 1966. The baby boy, weighing in at approximately 5.7 pounds, was delivered by cesarean section at Tokyo's Aiiku Hospital at 08:27. Princess Kiko's husband is Prince Akishino, 40, the second son of Emperor Akihito, 72. The Emperor's eldest son, Crown Prince Naruhito, 46, has only one child, four-year-old Princess Aiko. The new baby stood third in line after his uncle and father, according to Japan's Imperial Household Law, while Prince Hitachi, the Emperor's brother, moved down to fourth. The 1947 Law bars females, as well as males of matrilineal descent, from assuming the throne.

Some press reports noted that the birth only postponed the looming succession crisis for Japan's 23-member Imperial family. Previously, only nine children had been born into the family in the past 40 years, and all were female. With no male members of the Imperial family under the age of forty, and collateral noble families descended from earlier emperors excluded from the line of succession, there was a possibility that there would be no eligible successor to the throne after the deaths of Crown Prince Naruhito and Prince Akishino.

When the Meiji Imperial House Law and again the current Imperial House Law were enacted,various grounds were cited for institutionalizing the principle of male succession through malelineage, these being rooted in the circumstances of the day.Specifically, at the time of the enactment of the Meiji Imperial House Law, such argumentswere made as the following:

- A female Emperorís dignity would be diminished by the presence of a consort, for Japanese popular sentiment and social norms gave precedence to the male.

- The Japanese system of inheritance favored males. If the eldest child was a daughter but she had a younger brother, the estate went to the latter.

- In the minds of the Japanese people, female Emperors had throughout history always served a provisional, interregnal role, and Imperial succession was still perceived as passing through the male line. Moreover, these female Emperors had been without consorts during their reigns; but a system that compelled a female Emperor to remain unwed today would be at odds with both reason and popular sentiment.

- A child born of a female Emperor would inherit her husbandís surname; the Imperial line would thus be diverted into a different course in violation of tradition.

- The consort of a female Emperor might interfere through her in affairs of State.

- A womanís assumption of the highest position of political authority would be inconsistent with the absence of female suffrage in Japan. Similarly, when the current Imperial House Law was enacted, such arguments were made as these:

- The Imperial succession had, in so far as past precedents were concerned, always run through the male line, and that was consistent with popular sentiment.

- Historically speaking, female Emperors had always served a provisional, interregnal role.

The principle of male succession through male lineage was basically predicated on the assumption that Emperors and male members of the Imperial Family are always going to father sons. Among the reasons why this practice has been maintained for so long in the past can be cited the fact that succession to the Throne by illegitimate offspring was once widely accepted. The large role that this has played in the maintenance of male succession through male lineage is evident from the fact that nearly half of Japanís Emperors have been of illegitimate birth. Another important factor has been that people once generally married young, and bearing large numbers of children was the norm in the Imperial Family as well.

The Imperial Household Agency announced shortly after the birth that the newborn would receive approximately USD 25,000 per year, the same as his two older sisters, ages 14 and 11. Prince Akishino receives ten times that amount, as stipulated by the Imperial Household Law, for purposes of "maintaining the royal dignity."

Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Secretary General Tsutomu Takebe sent congratulations to the Imperial family on behalf of the ruling party, as did Chief Cabinet Secretary Shinzo Abe [the next prime minister]. Opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) Secretary General Yukio Hatoyama hailed the birth as well, and called for a moratorium on further discussions of amending the succession provisions of the Imperial Household Law for the time being.

Prime Minister Koizumi announced on 20 January 2006 that he would submit a bill to the Diet to revise the Imperial Succession Law to allow females and their descendants to ascend the Chrysanthemum Throne. Calling for "cautious discussion," he expressed his desire to gain unanimous approval for the bill in order to prevent the succession issue from turning into a political fight. However, even many of his own LDP members did not support the bill. Calls by Foreign Minister Aso and Finance Minister Tanigaki for more debate did not bode well for speedy passage. In the end, Prime Minister Koizumi's decision to seek unanimous Diet approval made it more impossible to submit the bill after it the unexpected February 8 announcement that Princess Kiko was pregnant. Chief Cabinet Secretary Abe publicly confirmed that the bill would be shelved on February 10, after which debate seemed to die down almost completely, as most Japanese eagerly awaited the birth.

According to poll results published in the 12 February 2006 Mainichi Shimbun, 78 percent of respondents were ready to accept a female monarch, with 52 percent in favor of revising the Law even if a male heir were born. The Imperial family did not disclose in advance whether the child was a male or female this time, perhaps in hopes of avoiding the sort of national hysteria that surrounded the birth of Princess Aiko in 2001.

The Japan Conference, a suprapartisan group of Diet members is chaired by former trade minister Takeo Hiranuma; the Japan Conference, a group of people from the private sector chaired by former Supreme Court Chief Justice Toru Miyoshi; and the Group Studying the Imperial House Law, which is headed by Shoichi Watanabe, professor emeritus at Sophia University, held a meeting February 2, 2009 at the Parliamentary Museum in Nagatacho, Tokyo. In the meeting, the three groups adopted a resolution opposing a "hasty revision to the Imperial House Law." They are concerned that if the government forces the measure through, public opinion will be split, and the Emperor's status could even be threatened.

There was a view common to the Ibuki and Komura factions favoring caution regarding the revision of the Imperial House Law, which is designed to allow females and their descendents to ascend to the Chrysanthemum Throne. The Japan Conference, a suprapartisan group of Diet members chaired by Takeo Hiranuma, has collected signatures from 135 LDP lawmakers as of 01 February 2009 on a document seeking prudence on revising the Imperial House Law.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|