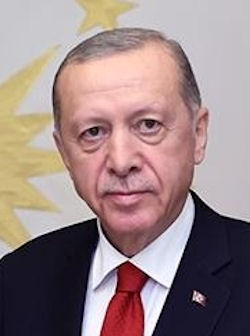

Recep Tayyip Erdogan

Born in Istanbul to a family from the Black Sea, and with dreams of becoming a professional football player in his youth, Erdogan proved highly appealing to those who are sometimes called "Black Turks": conservative, often religious, and poorly educated voters, who had long felt abandoned by previous secular and Western-leaning governments. Over the last 20 years, Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) put them in the driving seat of the country.

Born in Istanbul to a family from the Black Sea, and with dreams of becoming a professional football player in his youth, Erdogan proved highly appealing to those who are sometimes called "Black Turks": conservative, often religious, and poorly educated voters, who had long felt abandoned by previous secular and Western-leaning governments. Over the last 20 years, Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) put them in the driving seat of the country.

Erdogan's hunger for absolute power and for the material benefits of power were immediately evident, but did not erode his grassroots popularity. Erdogan came to power in 2002 as an Obama-like personality but came to resemble President Bush. By 2008 the original pro-reform PM had morphed into a status-quo nationalist politician. Erdogan came to power as a pluralistic leader who championed European Union reforms and promised a progressive approach to solve the Kurdish issue but over time shifted to a pro-state, pro-military stance. The increasingly autocratic and out of touch prime minister lashed out at critics with increasingly irascible outbursts.

His early years marked one of the most open periods of modern Turkish history: opening up the economy to attract foreign capital; holding direct negotiations with the Kurdish PKK (since 1984, a civil war had killed tens of thousands); and allowing veiled women access to university, the army and civil service.

The former Islamist militant allowed yearly Gay Pride parades until 2014, when close to a million revellers filled the streets of Istanbul. His country was the first to ratify the Council of Europe's Convention on preventing and combatting violence against women (informally known as the Istanbul Convention).

But in May 2013, protests against a plan to build a shopping center in Gezi Park in Istanbul marked a turning point, with police violence. Soon afterwards, the emergence of Kurdish groups close to the PKK in the Syrian conflict contributed to the breakdown of negotiations with the terror group in Turkey.

On 10 August 2014, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan was declared the winner of Turkey's first-ever direct presidential election. Results released by the country's electoral commission showed Erdogan winning an outright majority over his two opponents, thus allowing him to avoid a runnoff election.

With family origins in Turkey's Rize, Recep Tayyip Erdogan was born in Istanbul on February 26, 1954. He graduated in 1965 from Kasimpasa Piyale Elementary School and in 1973 from Istanbul Religious Vocational High School (Imam Hatip Lisesi). Erdogan received his high school diploma from Eyüp High School where he took a graduation exam. Erdogan graduated in 1981 from Marmara University's Faculty of Economics and Commercial Sciences.

Erdogan's charisma, defensiveness, strong intuition, commanding (even authoritarian) presence, common touch -- rare among Turkish politicians -- and slight swagger came from having to make his way as a youth in the gritty Istanbul neighborhood of Kasimpasa, attending a preacher (imam-hatip) high school, and playing professional soccer. He is both prone to emotional reactions and cool in wielding political power. He had a huge self-image and heightened sense of pride, both easily wounded when he thinks he is not being shown due respect, and reacts badly to criticism. Yet he proved he has a strong pragmatic streak as mayor of the 12 million-strong Istanbul, in trying to break out of sclerotic approaches to Cyprus, and in having a well-tuned (if acquired) sense of timing on when to push and when to hold back on sensitive questions like the headscarf issue.

Preferring to blend his social life with politics from his early days, Erdogan embraced the disciplined teamwork and team spirit that football taught him ever since he first started to play the game at a young age. He engaged in the sport as an amateur over the years 1969-1982. It was also in those years that, as a young idealist, Recep Tayyip Erdogan began to feel a concern for national issues and the problems of society. This is when he took the first step in participating in active politics.

Preferring to blend his social life with politics from his early days, Erdogan embraced the disciplined teamwork and team spirit that football taught him ever since he first started to play the game at a young age. He engaged in the sport as an amateur over the years 1969-1982. It was also in those years that, as a young idealist, Recep Tayyip Erdogan began to feel a concern for national issues and the problems of society. This is when he took the first step in participating in active politics.

An active member of various branches of the Turkish National Students' Union in his high school and university years, in 1976, Recep Tayyip Erdogan was elected Chairman of the Beyoglu Youth Branch of the National Salvation Party, MSP, later to be elected Chairman of the Istanbul Youth Branches of the party in that same year. Erdogan continued to occupy these posts until 1980. Following the September 12 military intervention which closed down all political parties, Erdogan worked in the private sector as a consultant and a senior executive.

When the Welfare Party was established in 1983, Recep Tayyip Erdogan returned to politics and in 1984 he became Beyoglu District Chairman of that party. In 1985, he was appointed the party's Provincial Chairman for Istanbul as well as a member of its Central Decision-making and Executive Board. While acting as Provincial Chairman for Istanbul, Erdogan initiated a reorganization which served as a model for other political parties. In this period, Erdogan worked to increase the participation of women and young people in politics and took important steps in creating a grassroots movement by encouraging larger sections of the society to take an interest in politics. This reorganization earned the Welfare Party huge success in the Beyoglu district in the local elections of 1989, and became a model for political efforts all around the country.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan was elected Istanbul Mayor in the local elections of March 27, 1994. With his political skills, the importance he placed on teamwork, his successful management of human resources and financial matters, Erdogan was able to make correct diagnoses and create solutions for the many chronic problems of Istanbul, one of the most important metropolitan areas of the world. The water shortage problem was solved with the laying of hundreds of kilometers of new pipelines. The garbage problem was solved with the establishing of state-of-the-art recycling facilities. Air pollution was eliminated while Erdogan was in office with a plan that was developed to switch to natural gas. The city's traffic and transportation jams were tackled with more than 50 bridges, viaducts and highways.

Many projects that would shed light on the problems of later years were developed. Erdogan further took measures to ensure that municipal funds were used prudently, at the same time taking severe precautions to prevent corruption. Erdogan paid back a major portion of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality's debt, which was two billion dollars when he took office, and meanwhile invested four billion dollars in the city. Opening an entirely new era in municipality affairs in Turkey, Erdogan became a model for other municipalities, while also earning a high level of public trust.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan was sentenced to a prison term because of a poem he recited on December 12, 1997 in a public address in the province of Siirt. The poem was quoted from a book published by a state enterprise and one that had been recommended to teachers by the Ministry of Education. Erdogan had spent 120 days in jail in 1999 for "inciting animosity and hatred" by quoting a poem that said, "minarets are our bayonets, domes of the mosques our helmets, and mosques our barracks, believers our soldiers". He was removed from the office of Istanbul Mayor due to this.

Erdogan was convicted under Article 312(2) for "inciting religious hatred". Article 312(2) was revised as part of the EU-related reform package passed in August 2002, and a Diyarbakir State Security Court ruled in September 2002 that Erdogan's record should be erased because his speech no longer constituted a crime under the revised language. However, the High Court of Appeals overruled the lower court decision; subsequently the Supreme Election Board determined Erdogan ineligible to run in the November 3 elections. Article 76 of the Constitution states that anyone convicted of "ideological" or "anarchistic" activities, generally interpreted as including anyone convicted under Article 312(2), is not eligible to be elected to Parliament, even if pardoned.

After four months in prison, Recep Tayyip Erdogan responded to the insistent demands of the public in an environment of improved democratic conditions, and established the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) with a group of friends on August 14, 2001. He was subsequently elected Founding Chairman of AK Party by the Founding Board. From its first year, the confidence and trust of the people in AK Party resulted in its becoming the largest publicly-supported political movement in Turkey. In 2002, the general elections resulted with AK Party winning two-thirds of the seats in parliament, forming a single-party government.

Not permitted to become a candidate deputy in the elections of November 3, 2002 because of the court order against him, Erdogan participated in the renewal elections for the province of Siirt on March 9, 2003 upon the lifting of the legal obstacles to his candidacy for parliamentary membership. Receiving 85 percent of the votes in this election, Erdogan became a deputy for the province of Siirt for the 22nd Term of Parliament.

Appointed Prime Minister on March 15, 2003, Recep Tayyip Erdogan continued to harbor his ideal of a bright and rapidly developing Turkey, implementing numerous reforms of vital importance within a short period of time. Despite his popularity in urban sprawls and across Anatolia, Erdogan was far from being universally liked. Indeed, he was loathed by most of the Establishment. The Establishment preferred to portray him as a mediocrely educated, local tough guy made (too) good, a charismatic but dangerous preacher-politician who will lead Turkey to the Sharia.

A great deal was achieved in democratization, attaining transparency and preventing corruption. Parallel to this, inflation, which had adversely affected the country's economy and the people's psychological state of mind for decades, was finally taken under control and the Turkish Lira retrieved its former prestige through the elimination of six zeros. Interest rates for public borrowings were pulled down, per capita income grew significantly. A host of new dams, housing projects, schools, hospitals and power plants were inaugurated at a pace never before witnessed in the history of the country. All of these positive developments were named "the Silent Revolution" by some foreign observers and Western leaders.

By 2008 Erdogan had little choice in shifting his political stance toward more status-quo policies. The Turkish Constitutional Court case to close the ruling AK Party (which was rejected) brought further distraction from the political, economic and constitutional reforms needed. By failing to close AKP by just one vote, the Constitutional Court and the state establishment had sent AKP a stern message. Erdogan understood that AKP escaped closure by a "hair's breadth," and therefore shelved AKP's project to write a new civilian constitution and made an "implicit bargain" with the military establishment. But the absence of checks on Erdogan's power came with a heavy cost. Focusing on winning elections above all else, Erdogan showed little evidence of a statesman's vision for Turkey, and appears to have shed his previous reformist spirit in favor of a more pronounced nationalist stance.

With his semi-pro soccer player's swagger and phalanx of sycophantic advisors, by 2004 he was the man who won Turkey the beginning of accession negotiations with the EU. Who broke loose three decades of frozen Turkish policy on Cyprus. Who drove major human rights reforms through parliament and through constitutional amendments. Whose rhetorical skill, while etched with populist victimhood, is redolent with traditional and religious allusions that resonate deeply in the heartland, deeply in the anonymous exurban sprawls. Who remained the highly popular tribune of the people, without a viable or discernible political rival.

In addition to the major initiatives that had been characterized as turning points in the country's journey toward becoming a member of the European Union, Recep Tayyip Erdogan's foreign policy and intensive diplomatic visits paved the path for a lasting solution in the Cyprus issue and the development of productive relations with several countries around the world.

A broad range of senior career civil servants and many others expressed shock and dismay at the incompetence, prejudices and ignorance of appointees, noting the poor quality of Erdogan's and AKP's appointments to the Turkish bureaucracy, at party headquarters, and as party mayoral candidates. The result was that, unlike former leaders such as Turgut Ozal or Suleyman Demirel, both of whom appointed skilled figures who could speak authoritatively for their bosses as their party general secretary and as Undersecretary of the Prime Ministry, Erdogan left himself without people who can relieve him of the burden of day-to-day management or who can ensure effective, productive channels to the heart of the party and the heart of the Turkish state.

Erdogan's pragmatism served him well but he lacked vision. Erdogan had steadily arranged for the departure of those who disagree with him. AKP had become devoid of previous pillars who helped leaven Erdogan's often hot-headed political street sense. He and his principal AKP advisors, as well as other ranking AKP officials, lacked analytic depth. He relies on poor-quality intel and on media disinformation. With the narrow world-view and wariness that lingers from his Sunni brotherhood and lodge background, he ducked his public relations responsibilities. He (and those around him) indulged in pronounced pro-Sunni prejudices and in emotional reactions that prevented the development of coherent, practical domestic or foreign policies.

In surrounding himself with an iron ring of sycophantic (but contemptuous) advisors, Erdogan has isolated himself from a flow of reliable information, which partially explains his failure to understand the context -- or real facts -- of the U.S. operations and his susceptibility to Islamist theories. With regard to Islamist influences on Erdogan, Davutoglu was described as "exceptionally dangerous." Erdogan's other foreign policy advisors (Cuneyd Zapsu, Egemen Bagis, Omer Celik, along with Mucahit Arslan and chef de cabinet Hikmet Bulduk) are despised as inadequate, out of touch and corrupt.

When Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan opened a $500 million, 1,000-room presidential palace in October 2014, critics compared the grandiose Ankara residence to one being built by former Romanian communist dictator Nicolae Ceau?escu on the eve of his downfall. Commentators asked why Turkish presidents would need such an opulent palace when the office is largely ceremonial, restricted to approving legislation. But the answer soon became increasingly clear. Since switching from the premiership with his August 2014 election to the presidency, Erdogan began grabbing more powers for himself and forming what opposition commentators claim is a "shadow government." It's part of an effort, they say, to reclaim power over ministers and the country’s parliament that he'd lost when he left the prime minister's office.

In July 2016, following a failed coup d'Etat, Erdogan declared a state of emergency. In the months that followed, tens of thousands of people were arrested, and the army was purged. Officially, they were accused of supporting Fethullah Gülen, a preacher and former ally of the head of state. In reality, all those who denounced the government's policies - in particular regarding human rights - were targeted. In July 2021, Erdogan pulled Turkey out of the Istanbul Convention.

For the president's electoral base, these events are regarded as distant echoes that have no bearing on their day-to-day lives. the CHP, the secular outfit founded by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, won the municipal elections in all the country's biggest cities in 2019. By forming a coalition with five other opposition parties, it hoped to put an end to the Erdogan era in the elections scheduled for mid-2023.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan is married and the father of four. Lacking a strong, well-rounded education, Erdogan relies on his intuitions, presence, and ability to bond to manage meetings with foreign interlocutors. He will listen intently and expects his interlocutors to treat him and the subject seriously, even earnestly. At the same time, he is open to the well-timed joke or lighter comment. In the latter regard, Erdogan is a passionate fan of Fenerbahce, nicknamed the Yellow Canary, one of the big three Istanbul (and Turkish) soccer clubs; a gift with a yellow or yellow and blue motif would be a hit, especially if accompanied by a comment relating to his passion for soccer.

Erdogan's style is to make his points initially softly and laconically; if he meets resistance he ratchets up his second response, becoming more stern with each exchange on the topic. He reacts badly to overt pressure or implied threats. The best way to convince him to take a tough decision is to appeal calmly but man-to-man to his sense of destiny as Turkey's leader.

Erdogan's street-fighter instincts combined with years of non-stop political pressure led him to adopt an increasingly obdurate attitude over time. Erdogan is a captive of his background: those from the Black Sea, like Erdogan tend to be emotional and pugnacious. Erdogan's hunger for power revealed itself in a sharp authoritarian style and deep distrust of others: as a former spiritual advisor to Erdogan put it, "Tayyip Bey believes in God... but doesn't trust him."

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan managed to score a very similar percentage of votes in the 28 May 2023 election compared with the 2018 presidential polls. Anadolu Agency had Erdogan winning 52.2 percent of the vote, despite a painful cost-of-living crisis in the country and twin earthquakes that killed tens of thousands of people in February. The opposition had believed that the problems Erdogan faced would be enough to finally unseat him, but that was not to be.

Erdogan said 08 March 2024 the country’s upcoming local elections on March 31 would be his last. “This is a final for me, under the mandate given by the law this is my last election,” Erdogan said. “The result that will come out will be the transferring of a legacy to my siblings who will come after me.” He was re-elected for a five-year term in May 2023.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|