The Headscarf Issue

The conflict between secularism and Islamism in Turkey often has been joined over head scarves. Turks have argued about the permissibility of veiling since the 1980s. The issue of veiling marks the intersection between modernization and the Islamic movement and is a symbolic marker of the meaning of women's bodies. Turkish women wear a traditional long head scarf that has nothing to do with a modern Islamic head scarf. Turkish and Indian women are pressured by fathers, husbands, and brothers to completely cover themselves. Turkish women who put on the veil come from modest social origins, peripheral cities, and small towns with a conservative background. Turkish women wearing the veil do so when they move to urban areas and pass the university entrance exams. Rural women maintain the classical head scarf. Urban women wearing veils are leaving the domestic space and private sphere and distancing themselves from traditional women's roles. These Islamic radical women are a small minority of about 10% of the population. Most of the population follow a modern way of life with a different ideology.

After the Islamist Refah Party came to power in June 1996, enforcement of laws prohibiting the wearing of head scarves in public institutions appeared to weaken and the increased popularity of the apparel provoked the secular establishment. One of the National Security Council's February 28, 1997 "recommendations" to the government stated, "practices in contravention of the law on attire that could give Turkey a backward appearance should be obstructed and laws in this regard should be enforced especially in public institutions." For some women, the wearing of a head scarf or hijab soon became a symbol of defiance of the military and other secularists in addition to an expression of religious belief. On the other side of the issue, secular women saw the head scarf as a symbolic Islamist challenge to the improved status they had achieved since the Republic was founded.

Enforcement of the ban on head scarves in public institutions has produced conflict. In January 1998, the Ministry of Education issued a decree calling for stricter enforcement of the dress code in schools, provoking demonstrations. Several hundred women teachers throughout the educational system have been fired for wearing head scarves. Before the academic year began in fall 1998, the Higher Education Council ruled that women students would be issued campus identification cards only if they submitted a photograph in which they were not wearing a head scarf. Students who wear head scarves viewed the ruling as a requirement that they violate what they consider to be Quranic injunctions in order to get an education, and as a restriction on their right to religious expression. They took to the streets in demonstrations throughout the country in October 1998.

The ban was strictly enforced on some campuses and less strictly enforced on others, apparently depending on the views of university administrators. In December 1999, the Turkish Supreme Court of Appeals agreed with a lower court ruling against a student who had sued Istanbul University, holding that wearing head scarves was not a "democratic right." In 1993, the European Commission of Human Rights had ruled in a related case in which a university graduate was not granted a degree certificate after she had refused to submit a photograph of herself without a head covering because it was against her religious beliefs. After the Turkish judicial system denied her relief, the European Commission held that by choosing to attend a secular university the student had submitted to the university's rules. It refused to allow the case to go further.

The head scarf issue was dramatized after the April 1999 national election. Merve Kavakci, elected as an Islamist Fazilet or Virtue Party deputy, chose to wear a head scarf to the swearing in ceremony of the Grand National Assembly in open contravention of the law. Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit?s Democratic Left Party led the opposition to Kavakci's presence in the Assembly in a head scarf, and she was shouted out of parliament. President Demirel then accused Kavakci of being a foreign agent, implicitly of Iran,71 and the Foreign Ministry summoned the Iranian Ambassador to Turkey to protest demonstrations of sympathy for Kavakci that had taken place in Teheran. The government subsequently deprived Kavakci of her Turkish citizenship on the grounds that she had acquired U.S. citizenship without permission of Turkish authorities, and the courts have upheld the government's action. Kavakci's supporters charged the government with selective enforcement of the law. Kavakci's critics accused her and Fazilet of exploiting religion for political purposes. They cite the contrasting case of Nesrin Unal, a newly elected woman member of parliament for the Nationalist Action Party, who wears a head scarf elsewhere but chose to obey the law and not wear one in the Assembly. She was applauded by the secularists when she took her oath of office with a bare head.

Before she becoming the 'first lady', Abdullah Gül's wife Hayrünisa Gül had been known publicly because of her application to the 'European Court of Human Rights' (ECHR). Although she had succeeded the university entrance exam, her registration had not been made by the university, on the ground that one could not attend higher education institutions with a headscarf. Upon the rejection of her case by Danıştay (the Council of State in Turkey), Ms. Gül brought the case before the ECHR. She, however, withdrew her application following the appointment of Abdullah Gül as the foreign minister in 2003.

As of 2010 authorities continued to enforce the long-standing ban on the wearing of headscarves by civil servants in public buildings and by students in universities. Women who wear headscarves and persons who actively show support for those who defy the ban have been disciplined or have lost their jobs in the public sector as nurses and teachers. At the same time, there were unconfirmed reports that employees in governmental ministries faced discrimination because they were not considered by their supervisors to be sufficiently observant of Islamic religious practices.

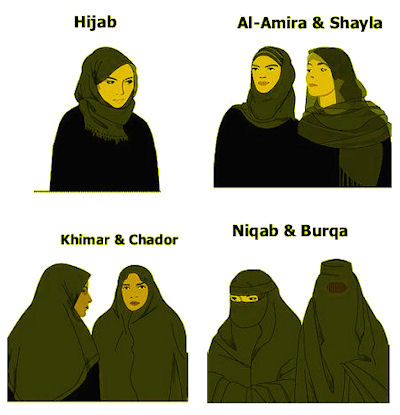

According to the Koran, [24.31] "And say to the believing women that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty; that they should not display their beauty and ornaments except what (must ordinarily) appear thereof; that they should draw their veils over their bosoms and not display their beauty except to their husbands, their fathers, their husband's fathers, their sons, their husbands' sons, their brothers or their brothers' sons, or their sisters' sons, or their women, or the slaves whom their right hands possess, or male servants free of physical needs, or small children who have no sense of the shame of sex;" In many parts of the Muslim world where it is not required by the law, covering with the hijab (headscarf) is actually on the rise. In fact, in some countries, more younger women are wearing hijab than in their mothers' generation. The Hijab is the most common Muslim veil used by Muslim women, however there are more types of veils. Many women choose to go even further, wearing the niqab, which covers the entire face. Some wear black gloves.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|