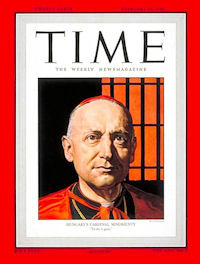

Cardinal Mindszenty

Jozsef Cardinal Mindszenty, who died on 6 May 1975 in Vienna at the age of 83, remains a symbol of resistance in the fight for the freedom of religion under communism. His power as a symbol of resistance to communism has compelled the Hungarian government to engage in an unabated campaign of propaganda against him.

Jozsef Cardinal Mindszenty, who died on 6 May 1975 in Vienna at the age of 83, remains a symbol of resistance in the fight for the freedom of religion under communism. His power as a symbol of resistance to communism has compelled the Hungarian government to engage in an unabated campaign of propaganda against him.

Joszef Mindszenty was born on 29 March 1892 to Janos and Borbala (Kovacs) Pehm in the Hungarian village of Csehimindszent in Vas county. He was one of six children in a peasant family of Germanic origin (on his father's side) that had lived in Hungary for about 300 years. Forty-nine years later, in 1941, in defiance of the Nazi campaign to have Hungarians of German descent revert to their Germanic names, he discarded the name Pehm and adopted part of the name of his native village. He attended a Catholic boarding school in the town of Szombathely, where he later studied at the seminary. On 12 June 1915 he was ordained and on June 29, according to the custom of the country, he celebrated his first Mass in his native village. Shortly afterward he became a curate at the church in Felsopaty. In 1919 he was imprisoned by the communist regime of Bela Kun because of his opposition to communism. Following the collapse of the Hungarian Soviet Republic he became parish priest and rural dean in Zalaegerszeg and in 1924 was given the honorary title of abbot. He was appointed papal prelate in 1937 and on 29 March 1944 he was consecrated Bishop of Veszprem.

Mindszenty's opposition to the government's cooperation with the occupying Nazis and his protests against the persecution of the Jews made him an enemy of the Arrow Cross regime. Charged with treason, he was arrested on 17 November 1944 and was kept in custody until April 1945, about two months after the capture of Budapest by the Soviet Army.

In 1945 the church lost its landed property in the first postwar land reform, which occurred before the communist takeover. Most Catholic religious orders (fifty-nine of a total of sixty-three groups) were dissolved in 1948, when religious schools were also taken over by the state. Most Catholic associations and clubs, which numbered about 4,000, were forced to disband. Imprisoned and prosecuted for political resistance to the communist regime were a number of clergy, most notably Cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty, primate of the Catholic Church in Hungary.

On 7 October 1945 the Vatican appointed Mindszenty the Primate of Hungary and Archbishop of Esztergom. Mindszenty soon proved to be just as relentless in his defense of human rights under communism and became an uncompromising critic of the new regime.

The government expropriated the churches' property with land reform, and in July 1948 it nationalized church schools. Protestant church leaders reached a compromise with the government, but the head of the Roman Catholic Church -- Cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty -- resisted.

In August 1948 Janos Kadar succeeded Laszlo Rajk as Minister of Internal Affairs. Kadar continued the campaign against the Church, which culminated in Mindszenty's arrest on 26 December 1948. Forseeing his arrest, the cardinal issued a statement in advance saying that any confession on his part to the charges of the communist authorities would only be the result of "human frailty" and declared "all such actions null and void." He was brought to trial after six weeks of physical torture and forced treatement with drugs at the secret police headquarters in Budapest, and was sentenced to life imprisonment on 9 February 1949 after "confessing" to treason, attempting to overthrow the government, espionage, and foreign currency abuses. Cardinal Mindszenty confessed being guilty of the charges, in open court. What extenuating circumstances may have been behind the confession are unknown, in spite of the vast amount of speculation on the subject. Shortly thereafter, the regime disbanded most Catholic religious orders, and it secularized Catholic schools. His next eight years were spent in confinement; in July 1955 he was taken to Puspokszentlaszlo and in November 1955 he was transferred to the village of Felsopeteny.

On 30 October 1956, a week after the beginning of the Hungarian Revolution, Mindszenty was freed by the soldiers of the Hungarian Army, After the crushing of the revolution Mindszenty took refuge in the American Embassy. Cardinal Mindszenty was given asylum at the American Embassy in Budapest by President Eisenhower. The Cardinal languished there for fifteen years, unable to leave the building. The Government of the United States of America gave shelter to Cardinal Joseph Mindszenty in this building between November 4, 1956 - September 28, 1971.

During his time in the Embassy, the Cardinal took up residence in the office suite now used by the US Ambassador. He used what is now the Ambassador's office as his salon or sitting room, and he slept in the other, smaller room to the side. The police outside the Chancery were ever watchful should he try to escape, and they ran their engines day and night, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, just in case.

There appeared to be a very general (and perhaps not unnatural) assumption by people outside Hungary that the Cardinal would welcome any opportunity to exchange his present place of refuge for a place of safety and a position of Church activity outside this country. Articles in the Western press were almost uniformly written with this assumption in mind. Even the Vatican appears to have expected that the Cardinal would be ready and anxious to avail himself of a safe conduct, if such were arranged for him.

The Cardinal was imbued with the very special position and powers exercised for many centuries by the Prince Primate of Hungary. The Holy See, however, seems to appreciate (as the Cardinal did not) that the "social revolution" which has occurred in Hungary since World War II has seriously altered (if, indeed, it has not brought to an end) that "special position".

The Cardinal was imbued with the very special position and powers exercised for many centuries by the Prince Primate of Hungary. The Holy See, however, seems to appreciate (as the Cardinal did not) that the "social revolution" which has occurred in Hungary since World War II has seriously altered (if, indeed, it has not brought to an end) that "special position".

As late as April 1957, the Holy See was evincing the desire "to discuss the Cardinal's departure on quid-pro-quo basis with view to extract some concessions from Kadar's regime". While any such concept was unrealistic, even at that date, the Holy See has been in a position, during the intervening eighteen months, to understand the radical changes that have occurred and to alter its concepts and its policy accordingly. Cardinal Mindszenty has not been in such a position; isolated, as he is, from almost all Church developments and from spiritual contact with the Holy See, his views and concepts have fallen behind and out of line with those of his spiritual mentors.

The Hungarian refusal to grant Cardinal Mindszenty a safe conduct to attend the Conclave of the Sacred College of Cardinals to take part in the election of the Pope, did not surprise observers, who predicted all along that the Hungarians will describe the American request asking for permission for Cardinal Mindszenty to leave Hungary as `gross interference in the internal affairs' of their country.

The Cardinal had a peculiar view of his presence in the embassy that was not shared by the rest of the staff. Among other things, the Cardinal felt that he was the legitimate ruler of Hungary. He felt that because he didn't recognize the Communists as being legitimate, he believed that Hungary was still a kingdom, and that since when there was no regent, when there was no king you had a regent, and when there was no regent, the prince primate of the church was in charge until a regent was appointed. So, he really did have it in his head that, under Hungarian tradition, he had a role there. Now, no one else recognized this role. The Vatican did not; the Communists certainly did not. He was a complication for all - for the United States, for the Hungarian government, and for the Vatican.

Those in close, daily contact with the Cardinal had long been aware of his thinking on the "deep spiritual problems" which his present situation creates and felt that some means should, if at all possible, be found to give the Holy See a just appreciation of his mental conflicts and to give him the benefit of guidance and assistance from his spiritual leaders. The almost complete lack of understanding between the Cardinal and the Holy See became clearly manifest and it was only with the greatest of reluctance that the Cardinal finally gave his assent to departure if a "satisfactory" guarantee could be obtained from the Hungarian Government. The Cardinal had no faith in any promises from the present Hungarian regime and fully anticipated the worst, if an attempt had been made to take him to Austria under any such "safe conduct".

The Vatican itself was not of one mind with respect to the policy which it should follow in the matter of the Cardinal's remaining in or departing from Hungary. The direct, official word through the Office of the Apostolic Delegate in Washington was to the effect that he should remain. When, however, a seemingly advantageous opportunity to have the Cardinal leave the Legation and the country presented itself, the Vatican became intent upon his availing himself of such opportunity and considerable pressure was put upon him by the Holy See to follow this course. One is left to speculate whether it was not, perhaps, Pius XII who was inclined to inaction earlier, with the result that those in favor of another policy were in a position to act only after Pius XII had left the scene.

During the 1960s, the two sides gradually reached an accommodation. In 1964 the Hungarian leadership concluded a major agreement with the Vatican, the first of its kind involving a communist state. The document ratified certain episcopal appointments already made by the church, although it did not settle Mindszenty's long-standing case. As before, the agreement mandated that certain individuals in positions in the church were obliged to take an oath of allegiance to the Constitution and the laws of the country. But this oath was to be binding only to the extent that the country's laws were not in opposition to the tenets of the Catholic faith. The church conceded the state's right to approve selection of high church officials. Under the agreement, the Hungarian Roman Catholic Church could staff its Papal Institute in Rome with priests endorsed by the government, and each year every diocese in the country would send a priest to Rome to attend the institute. For its part, the government promised not to interfere with the institute's work.

In 1971 Mindszenty had received permission to leave the country after spending many years in the American embassy in Budapest. The US Ambassador had tried for many years to convince Mindszenty to leave the Embassy. The Cardinal would pretend to go along but then would have a but at the last minute he'd change his mind. Pope Paul VI, was persuaded to write a letter to Mindszenty asking him to come to a special religious celebration conference that they were having in the Vatican at that time. The Pope's letter was written in a way that was strong enough that Mindszenty was able to interpret it as an order for him to appear. So, in any event, arrangements were then made for him to leave. A Hungarian irredentist to the end, Mindszenty angered the Austrians upon arrival in Vienna by announcing tha he was trying to get the old borders back. The Austrians saw this as an effort to claim the Burgenland, which had been ceded to Austria in 1920, for Hungary.

In 1974 he visited the United States, where he was warmly received by Hungarian emigres, who regarded him as their spiritual leader. Because he thought that Mindszenty's defiance of communism was interfering with his efforts at detente with the communist world, Pope Paul VI stripped Mindszenty of his offices of Primate of Hungary and Bishop of Esztergom in February 1974. Relations between church and state warmed particularly after 1974, when the Vatican removed Mindszenty from his office. The new primate, Cardinal Laszlo Lekai, who held office from 1976 to 1986, sponsored a policy of "small steps," through which he sought to reconcile differences between church and state

He was buried at a place called Mariazelle Etzel, which is a shrine and a place of pilgrimage outside of Vienna. However in 1990 he was then reburied in the basilica at Esztergom in Hungary, together with other past primates of Hungary's Catholic Church.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|