FS Surcouf (NN-3) "submarine cruiser"

The French Surcouf was a fascinating ship decades ago and undoubtedly remains so to this day. The fascination with it is caused by its gigantic, for the time of World War II, dimensions, unusual technical solutions, turbulent history, and a tragic end, full of ambiguities, which, despite the passage of time, still intrigue. The Surcouf was a submarine cruiser, designed for commerce-raiding, and featured many of the elements found in surface=bound commerce raiding cruisers.

Amongst the many Corsairs who gained wealth and renown in the last great war that was waged between France and England, the name of Robert Surcouf stands out pre-eminent. On his father's side, he was descended from another Robert Surcouf, who, in the early days of the eighteenth century, had commanded a vessel carrying letters of marque in the expedition which M. Chambert had led to Peru. Carrying cargo across the Seven Seas during the Age of Sail was a dangerous business at the very least since the days Drake and Frobisher first weighed their anchor in Plymouth. Thus, large merchantmen, more often than not, resembled warships and were heavily armed. Small wonder that Robert Surcouf's thoughts should have centred on the fame to be gained from privateering.

Robert Surcouf was a national hero. He had captured more than 40 merchant ships besides “Triton” and “Kent” during his career as corsair in the Indian Ocean between 1795 and 1809. Memories of Surcouf are quite ambiguous. He learned his trade on a slaver, smuggled slaves every now and then even after the Revolutionary government outlawed slavery in France and her colonies in 1794 and picked up the threads officially after stealing humans had become legal again under the Bourbons in 1816. The French privateering naval hero and slave trader Surcouf died at the age of 53 in his native Saint-Malo in Brittany on 8 July 1827.

The German High Command and the German Cabinet had very little idea of how to utilize their small submarine force at the beginning of the war, and no conception of the potential power which it placed in their hands; in fact they never did realize its possibilities, although, of course, many subordinates did. No effort was made to employ the submarines against the passage of the British Expeditionary Force to France, or against the line of supplies there until long after the beginning of hostilities. Neither was there any coordinated effort to employ the submarines in conjunction with the High Seas Fleet for an attack on the British Fleet until the Battle of Jutland at the end of May, 1916, and then the submarines were assigned to scouting duty and had no part in the actual battle.

During the fall of 1914 a limited commerce-raiding fare was carried out in accordance with Prize Rules in which about 100,000 tons of shipping was sunk. It seemed almost certain that had the Germans adopted the unrestricted submarine warfare in the summer of 1915, or even as late as the summer of 1916, instead of February, 1917, they would have thereby forced the Entente to sue for peace. During the Great War hostile submarines had been driven off by surface craft as regards any interference with communications, but it by no means followed that improved underwater vessels having large guns could be kept at bay by such means.

In the early part of the war, German U-boats would generally surface to attack enemy merchant ships which at this stage were largely un-armed. The ship’s crew would be given time to get into their lifeboats and pull away from the ship before it was sunk, either by gunfire or explosive charges laid by a boarding party. These boarding parties often took the opportunity to ‘requisition’ fresh food and other useful items before the ship went down. This situation drastically changed on the first of February, 1917, when the German Government authorised a policy of Unrestricted Submarine warfare. This allowed its U-boat commanders to attack and sink – without warning.

As early as 1915, one naval prognosticator ventured that "There is little doubt but that the expensive super-dreadnaughts will give place very shortly to something evolving through submersible destroyers into submersible battle cruisers; or submersibles which follow the principle of the battle cruiser, which consists in sacrificing weight of armor (but not calibre of guns) to speed. A submersible is as effectively protected by invisibility and by the water itself super-dreadnaught by its armor, and the submersible battle cruiser could follow the principle to its ultimate logical conclusion by being built without regard to defensive armor at all, provided it carried guns which could equal the range of the guns on board of the superdreadnaughts and was as fast as a torpedo boat destroyer. It is hardly to be disputed that the submersible battle cruiser, low-lying, small, agile as compared with its antagonist, would have every advantage..."

After the War, Admiral Beatty was reported to have said that "the ship of the future is the submersible battle cruiser," and that while battleships will not be superseded they "will be relegated to second place." As coming from the new First Sea Lord, the announcement suggests a revolutionary change of policy in the British Navy.

The authors of the provocatively titled "The Fate Of The Dreadnought" suggested in 1931 that "a submersible battle cruiser would have to be a ship mounting heavy guns, well furnished with torpedo tubes and encumbered with little or no armor because while on the surface she would lie awash, or nearly so, and would not need it. Further, the absence of armor would be an important consideration in the attainment of speed and wide cruising radius. Undoubtedly such a vessel would have important advantages. While on the surface, it would present a poor target to the enemy, it would theoretically, have a respectable surface speed and ability to keep the sea, and it could be able to deliver heavy blows with its great guns. It could also disappear beneath the sea and attack surface ships with the weapon and the tactics of the submarine. In co-operation with a surface fleet, it is easy to imagine such a vessel acting as a destroyer, making and repelling torpedo attacks and carrying out screening operations. It would be better than the destroyer in its vastly superior armament and in its power to submerge. In short such a type, if successfully developed, would combine the hard hitting power and the cruising radius of the battleship, united with the small exposure and submerging power of the submarine."

In view of the damage caused to British shipping by a small number of German submarines carrying only light guns, it seemed quite clear that under-water cruisers with large guns and greater speed would prove successful for blockading an enemy's coasts and for capturing enemy merchant vessels. The submersible principle had been applied successfully to vessels of from 1,000 to 2,000 tons, carrying guns as well as torpedoes. It was not impossible that in future a large proportion of the world's cruisers will be capable of submergence in order to avoid attack. A submersible battle cruiser would have little or no armor, because, while on the surface she would lie awash, or nearly so, and would not need it. The Navy would be unable to avoid responsibility for carrying out an effective patrol as a precaution against such vessels. Heavily armoed submarines might prove superior to surface craft, as a submarine having equal speed and gun power with a surface vessel would possess the advantage of being able to manœuvre underwater in addition to that of presenting a much smaller target.

The distinction between a submarine and a submersible consisted in the form, the method of construction and the buoyancy. The pure submarine has circular cross-sections and a hull in the form of a cigar; the ballast tanks in the interior of this hull and reserve buoyancy is small. On the other hand, the submersible has a form which approaches that of an ordinary ship and the cross sections are not circular; it possesses a double hull in whole or in part, the ballast tanks being formed by the space between the two hulls. The reserve buoyancy is great. As a matter of fact, due to the great strides made in submarine construction after the Great War and to the application to one type of ship of so many qualities which formerly were thought of as a distinct feature either of the submarine or submersible, the time arrived when all vessels that are capable of travelling beneath the water are classed generically as submarines.

No matter what type of construction was applied to a submarine, she will always be more or less of a poor, low and wet, gun platform and will provide only limited fire control facilities. Once the compromise between surface craft and submarine is permitted to swing too far in favor of the many desirable surface qualities, the value of the submarine as such, is decreased in proportion as the surface efficiency is enhanced. While the theorists' conception of a submarine may be a vessel capable of almost instantaneous transition from surface to submerged and submerged to surface capabilities, in practice, it will be found that it is not the merry proceeding of diving and surfacing like a porpoise but, in fact, that each maneuver requires the expenditure of altogether too many precious moments to get the vessel under proper control for gun or torpedo fire.

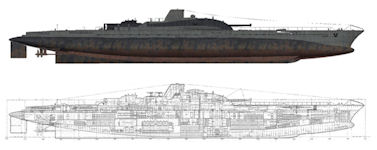

The Surcouf was designed in France in 1926, taking full advantage of the German experience in constructing large U-Boats heavily armed with artillery. In terms of size, it was much larger than the huge British M and X submarines built a bit earlier. Its technical parameters, range and armament fully justified classifying it as a submarine cruiser. All the more so as the gun's displacement and caliber corresponded to surface cruisers of that time, and additionally had light armor. Two more identical units were originally planned, but were soon abandoned. Surcouf was built in the Cherbourg arsenal. Its construction, from placing an order in December 1927, took three years. The launching ceremony took place on October 18, 1929, while the flag of the French Navy was hoisted in May 1934.

Numerous solutions to the construction of this ship were unique and even extraordinary. The imagination of the contemporaries was moved by the same size: the surface displacement was 3,252 tons, while the underwater displacement was 4,304 tons! For comparison, the tonnage of ORP Orzel and ORP Sep, the largest Polish submarines considered to be ocean-going vessels, too large for the Baltic Sea, amounted to 1,100 and 1,473 tons, respectively. Larger ships than the Surcouf were built by the Japanese in 1944/45. It was the so-called type I 400, which reached 5,223 tons of water displacement and 6,560 tons of underwater displacement.

The designers' basic assumption was that SURCOUF would function as a ship capable of ocean cruising operations. The large size of the vessel was the basic factor ensuring the record-breaking autonomy of sailing and a range of up to 10,000 nautical miles at a surface speed of 10 knots (70 miles in draft at 4.5 knots). A short-wave radio, using two large masts placed on the left side of the fuselage, provided excellent communication for those times. The reconnaissance at a considerable distance from the ship was to be carried out by a specially designed Besson MB 411 seaplane. The seaplane had its hangar behind the combat platform; it was a matter of just 10 minutes to assemble and prepare for flight. The equipment also included an almost 5-meter long motor cutter, intended for boarding activities. With this type of action in mind, special rooms for 40 prisoners were placed on the ship.

Harold A. Skaarup noted that "The boat encountered several technical challenges, owing to the 203-mm guns. Because of the low height of the rangefinder above the water surface, the practical range of fire was 12,000 m (13,000 yd) with the rangefinder (16,000 m (17,000 yd) with sighting aided by periscope), well below the normal maximum of 26,000 m (28,000 yd). The duration between the surface order and the first firing round was 3 minutes and 35 seconds. This duration could have been longer in case the boat was going to fire broadside, which meant surfacing and training the turret in the desired direction. Firing had to occur at a precise moment of pitch and roll when the ship was level. Training the turret to either side was limited to when the ship rolled 8° or more."

Surcouf is considered to be the last submarine whose main anti-surface armament was artillery. His armament was simply impressive. In front of the conning tower, a watertight turret was placed, and in this turret two 203 mm guns (design 1923) with a maximum range of approximately 27.5 kilometers. The barrel of each of these guns weighed 22 tons, and the bullet weight was 123 kg! the stock of 203 mm shells was 600 pieces. Behind the jetty, on the seaplane hangar, there were two 37 mm anti-aircraft guns with a reserve of 1000 rounds. Additionally, the armament included 2 coupled large-caliber (13.2 mm) machine guns. The torpedo armament consisted of 12 launchers: eight 533 mm caliber (4 in the bow and 4 in the stern, 14 torpedo reserve) and four 400 mm caliber (8 torpedo reserve) in the stern section.

Surcouf vanished on the night of 18/19 February 1942, about 80 mi (70 nmi; 130 km) north of Cristóbal, Colón, while en route for Tahiti, via the Panama Canal. It is often reported that Surcouf was rammed by the American freighter Thomson Lykes on its way to Panama. As a result of this disaster, it sank 70 nautical miles from Cristobal with all its crew. Rear Admiral Auphan wrote in his book The French Navy In World War II that “for reasons which appear to have been primarily political, she was rammed at night in the Caribbean by an American freighter.” However, it is not so certain. At the same time, an American plane reported the sinking of an unrecognized submarine in the area where the French giant might have been. James Rusbridger examined some of the theories in his book Who Sank Surcouf?, finding them all easily dismissed except one: the records of the 6th Heavy Bomber Group operating out of Panama show them sinking a large submarine the morning of 19 February.

The movie "Lorelei: The Witch of the Pacific Ocean" is a drama set during World War II where a submarine carrying a secret weapon attempts to stop a planned third atomic bombing of Japan, set to explode over Tokyo. Based on Harutoshi Fukui's best-selling novel Shuusen no Lorelei, the Y1.2b ($11.5m) Lorelei is blend of historical fact and manga-esque fantasy that mark it as distinctively Japanese. The result is an entertainment unlike anything else presently coming out of Asia, with more international potential that any of Kameyama's previous efforts. Unlike Wolfgang Petersen's grimly realistic DasBoot - another submarine feature told from inside a World War Two Axis vessel - Lorelei has the feel of a role-playing video game. At the tail end of World War II, a German submarine captain receives command of a special ship with advanced technology to prevent a third atomic bombing. The starring sub, the I-507, is a gift from the dying Nazi Reich to the Japanese navy during the closing days of World War II. Bearing a very strong resemblance to the French submarine Surcouf, the major changes being a more steeply angled bow and a docking platform for a German design Seehund minisub at the aft of the sail, it is equipped with imaging technology far in advance of the era's primitive sonar. Little does the captain know, but traitors lurk everywhere. Director Shinji Higuchi is an effects specialist who helmed three Gamera instalments and the 2001 Godzilla film. He and his team may not have had a Hollywood-sized budget, but their I-507 is a swift, dark, muscular thing of beauty and it was the highest-grossing film in Japan during the week of its release.