Spain - Climate

Peninsular Spain experiences three climatic types: continental, maritime, and Mediterranean. The locally generated continental climate covers the majority of peninsular Spain, influencing the Meseta Central, the adjoining mountains to the east and the south, and the Ebro Basin. A continental climate is characterized by wide diurnal and seasonal variations in temperature and by low, irregular rainfall with high rates of evaporation that leave the land arid. Annual rainfall generally is thirty to sixty-four centimeters; most of the Meseta region receives about fifty centimeters. The northern Meseta, the Sistema Central, and the Ebro Basin have two rainy seasons, one in spring (April-June) and the other in autumn (OctoberNovember ), with late spring being the wettest time of the year.

Peninsular Spain experiences three climatic types: continental, maritime, and Mediterranean. The locally generated continental climate covers the majority of peninsular Spain, influencing the Meseta Central, the adjoining mountains to the east and the south, and the Ebro Basin. A continental climate is characterized by wide diurnal and seasonal variations in temperature and by low, irregular rainfall with high rates of evaporation that leave the land arid. Annual rainfall generally is thirty to sixty-four centimeters; most of the Meseta region receives about fifty centimeters. The northern Meseta, the Sistema Central, and the Ebro Basin have two rainy seasons, one in spring (April-June) and the other in autumn (OctoberNovember ), with late spring being the wettest time of the year.

In the southern Meseta, also, the wet seasons are spring and autumn, but the spring one is earlier (March), and autumn is the wetter season. Even during the wet seasons, rain is irregular and unreliable. Continental winters are cold, with strong winds and high humidity, despite the low precipitation. Except for mountain areas, the northern foothills of the Sistema Iberico are the coldest area, and frost is common. Summers are warm and cloudless, producing average daytime temperatures that reach 21° C in the northern Meseta and 24 to 27° C in the southern Meseta; nighttime temperatures range from 7 to 10 C. The Ebro Basin, at a lower altitude, is extremely hot during the summer, and temperatures can exceed 43 C. Summer humidities are low in the Meseta Central and in the Ebro Basin, except right along the shores of in the Rio Ebro where humidity is high.

A maritime climate prevails in the northern part of the country, from the Pyrenees to the northwest region, characterized by relatively mild winters, warm but not hot summers, and generally abundant rainfall spread out over the year. Temperatures vary only slightly, both on a diurnal and a seasonal basis. The moderating effects of the sea, however, abate in the inland areas, where temperatures are 9 to 18 C more extreme than temperatures on the coast. Distance from the Atlantic Ocean also affects precipitation, and there is less rainfall in the east than in the west. Autumn (October through December) is the wettest season, while July is the driest month. The high humidity and the prevailing off-shore winds make fog and mist common along the northwest coast; this phenomenon is less frequent a short distance inland, however, because the mountains form a barrier keeping out the sea moisture.

The Mediterranean climatic region extends from the Andalusian Plain along the southern and eastern coasts up to the Pyrenees, on the seaward side of the mountain ranges that parallel the coast. Total rainfall in this region is lower than in the rest of Spain, and it is concentrated in the late autumn-winter period. Generally, rainfall is slight, often insufficient, irregular, and unreliable. Temperatures in the Mediterranean region usually are higher in both summer and winter, and diurnal temperature changes are more limited than those of the continental region. Temperatures in January normally average 10 to 13 C in most of the Mediterranean region, and they are 9 C colder in the northeastern coastal area near Barcelona.

In winter, temperatures inland in the Andalusian Plain are slightly lower than those on the coasts. Temperatures in July and August average 22 to 27 C on the coast and 29 to 31 C farther inland, with low humidity. The Mediterranean region is marked by Leveche winds--hot, dry, easterly or southeasterly air currents that originate over North Africa. These winds, which sometimes carry fine dust, are most common in spring. A cooler easterly wind, the Levante, funnels between the Sistema Penibetico and the Atlas Mountains of North Africa.

The country's climate "tends to have more subtropical characteristics. Higher temperatures and rarer and more intense rains. So climate-related risks -- heatwaves and rain and droughts and floods, will increase in the coming decades. Tourism is a key economic sector in Spain, and it is strongly weather dependent. The much higher temperatures forecasted for the summer would make summer temperatures unpleasant for many tourists.

The country's climate "tends to have more subtropical characteristics. Higher temperatures and rarer and more intense rains. So climate-related risks -- heatwaves and rain and droughts and floods, will increase in the coming decades. Tourism is a key economic sector in Spain, and it is strongly weather dependent. The much higher temperatures forecasted for the summer would make summer temperatures unpleasant for many tourists.

June 2017 was a scorching month all across Western Europe. As if stifling heat were not enough, the high temperatures combined with dry and windy conditions across the Iberian Peninsula to create the perfect environment for the production and spread of wildfires in Spain and Portugal. Aside from the dangers associated with heat-related illness during heat waves, hot and dry conditions in the summertime can easily turn vegetation into potential kindling, increasing the risk for wildfires. During June in central Portugal, a huge wildfire killed over 60 people and injured 200 more. In southwest Spain on June 24, wildfires were sparked in the Huelva province leading to the displacement of 1500 people and threatening Doñana National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Global climate change scenario experiments in Spain show that wheat yields generally increase, but maize yields significantly decrease. These reductions, along with exacerbated problems of irrigation water availability, may force the maize crop out of production in some regions by 2050. Spain and Portugal grappled with a devastating drought in 2017 which has left rivers nearly dry, sparked deadly wildfires and devastated crops -- and experts warn that prolonged dry spells will become more frequent.

Temperatures and soil moisture scarcity will increase, which will cause greater and more longlasting desiccation of fuels. Fuel flammability will therefore increase. Mean danger indices and, in particular, the frequency of extreme situations will increase. The average duration of the firedanger season will be prolonged. There will be more ignitions caused by lightening. There will be an increase in the frequency, intensity and magnitude of fires.

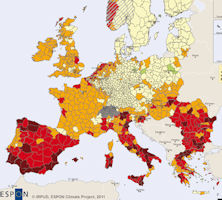

The climate-related natural hazards with the greatest impact in Spain, affecting terrestrial areas, include floods, droughts, landslides, avalanches, lightening, forest fires, gales, blizzards, hail, storms, cold spells, heat waves and subsidence affecting buildings and civil engineering works. The upward tendency of damages caused by natural disasters supports the idea that extreme events associated with the effects of climate change are occurring with greater frequency.

Increased torrentiality will cause a greater number of surface landslides and debris flow, the effects of which could be exacerbated by changes in land uses and less plant cover. Consequently, increased erosion is expected on slopes, along with a loss of quality of surface waters, due to increased turbidity, and a higher rate of clogging in reservoirs.

Due to Spain's being located near Africa, being a stopping-off point for migrating birds and individuals and due to its climate conditions, nearing those of areas where there are vector-borne diseases, this is a country where this type of diseases could taken on greater importance due to the climate change. The possible risk would result from the geographical spread of already established vectors or due to subtropical vectors adapted to surviving in cooler, dried climates being imported and taking up residence. Hypothetically, the vector-borne diseases subject to be influenced by the climate change in Spain would be those transmitted by dipterans, such as dengue fever, West Nile encephalitis, Rift Valley fever, malaria and leishmaniasis; tick-transmitted diseases, such as Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, tick-borne encephalitis, Lyme disease, spotted fever and endemic relapsing fever; and rodent-transmitted diseases. But the greatest, most viable threat would be the Aedes albopictus mosquito, which would be capable of transmitting viral diseases such as West Nile encephalitis or dengue fever, taking up residence. But, for actual areas of endemia being established, a combination of other factors, such as the massive, simultaneous influx of animal or human reservoirs and the deterioration of the social healthcare conditions and of the Public Health services.

Mainland Spain and Portugal broke temperature records for April, as both nations wilted in an unusually early heatwave that raised the risk of wildfires. The mercury hit 38.8 degrees Celsius (101.8 degrees Fahrenheit) in the airport in Spain's southern city of Cordoba on 27 Spril 2023, beating a previous record of 38.6C in the eastern city of Elche, national weather office AEMET said. In neighbouring Portugal, temperatures in the central town of Mora reached 36.9C, breaking the record of 36C set in April 1945 in the northeastern town of Pinhao, weather agency IPMA said. The scorching temperatures prompted warnings about the high risk of wildfires and worsened drought conditions that have already led some farmers in Spain not to sow seeds this year. The Spanish government said it would launch its forest fire monitoring campaign on Friday, a month and a half earlier than usual due to the early arrival of scorching temperatures.

Southern Spain will be reduced to desert by the end of the 21st century if the current rate of greenhouse gas emissions continue unchecked, researchers warned. Anything less than extremely ambitious and politically unlikely carbon emissions cuts will see ecosystems in the Mediterranean change to a state unprecedented in the past 10 millennia, they said. The study, published in the journal Science, modelled what would happen to vegetation in the Mediterranean basin under four different paths of future carbon emissions. A 2°C warming is likely over the next century to produce ecosystems in the Mediterranean basin that have no analog in the past 10,000 years.

After a long and painful drought, in April 2023 the country was hit by an unusually early heat wave, evaporating even more of the "blue gold" it still had left in its reservoirs. While farmers fear for their survival, environmentalists said it is time for “Europe’s back garden” to rethink how it uses and manages its increasingly scarce water supply. There’s an expression in Spain: “En Abril, aguas mil” – April will bring the rains. Only this year, it didn't. The month of April was the driest month on record, and several Spanish cities registered their highest April temperatures yet. In Cordoba, the mercury rose to 38.7°C (almost 102°F) at one point, and in the province of Seville in Andalusia to 37.8°C. Coming on the heels of a long-term drought and an unusually warm and dry winter, the latest heat wave has sparked a real fear of shortages.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|