Luftschiffbau Zeppelin

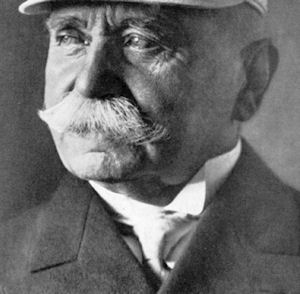

The German company Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, owned by Count Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin, was the world's most successful builder of rigid airships. During the European War the purposes for which these airships were employed were not those that Count Zeppelin intended when he began his efforts to construct them; his aim was to make a dirigible balloon able to travel across land and water to observe the movements of hostile fleets and armies, to carry persons or dispatches from one fleet station or army to another, but not to take an active part in the operations of actual warfare.

The German company Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, owned by Count Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin, was the world's most successful builder of rigid airships. During the European War the purposes for which these airships were employed were not those that Count Zeppelin intended when he began his efforts to construct them; his aim was to make a dirigible balloon able to travel across land and water to observe the movements of hostile fleets and armies, to carry persons or dispatches from one fleet station or army to another, but not to take an active part in the operations of actual warfare.

Ferdinand Count Zeppelin was born in 1838. Entering on a military career, he became an officer at the age of 20. Five years later he took part as a volunteer in the American Civil War on the Union side, and it was then that his taste for aeronautics originated, from his experience in going up at St. Paul in a balloon. Returning to his own country, he took part in the war between Prussia and Austria in 1866, and again saw active service in the war against France in 1870. After the war he continued his military career until 1891, when he retired with the rank of general. From this time he devoted his energies to the practical study of aeronautics.

In 1872, Paul Haenlein (who died in 1895) constructed an airship in Germany. Its shape was that of a solid formed by the revolution of a ship's keel about an axis lying on the deck. Careful hydrostatic experiments led him to the choice of this curious shape, which in the middle is more or less cylindrical, and at the ends somewhat conical. Its length was 164 ft., the greatest diameter 30 ft., and the capacity 85,000 cubic feet. The car was placed close to the body, in order that the parts might be as rigidly connected as possible. For the first time in the history of aeronautics it was proposed to use a gas engine, which was of the Lenoir type, and had four horizontal cylinders, giving 6 h.-p., with an hourly consumption of 250 cubic feet of gas. The gas for the engine was taken from the balloon itself, and the loss was to be made good by blowing out the air-bags. The car was made of beams running lengthwise, and was supported tangentially by ropes from the network. The envelope was made airtight by a thick coating of rubber on the inside, backed by a thinner one on the outside.

Being filled with coal gas it could not ascend to great heights, and the trials were therefore undertaken at a short distance from the ground, the balloon being kept in the captive state by ropes loosely held by soldiers. It attained a speed of 15 ft. per second, and this7 is an improvement of 6 ft. per second on the attempts of Dupuy de Lome. Lack of funds prevented any further attempts from being made, and though the project promised well and had some notable improvements, it was unable to proceed further. If Haenlein's results are compared with those of Lebaudy, who has reached a speed of 40 ft. per second, we can hardly doubt he would have achieved more if he had filled his balloon with hydrogen, and if light motors, of the type now in use, had then been available.

The first rigid airship was constructed by David Schwartz in 1893 in Petrograd. It was composed of aluminum and was not sufiiciently gas tight to be tested. However, in 1895 to 1897 he built in Berlin a new airship (47.5 m.) 155 ft. long (13.5 m.) 44.2 ft. in diameter, which had a total capacity of (3700 cu. m.) 130,500 cu. ft. The framework consisted of twelve rings and sixteen longitudinal aluminum girders and sheet aluminum was used for covering material. It was equipped with a Daimler engine developing 12 hp. at 480 r.p.m. The ship was inflated by using an interior bag, which, as soon as it was filled and the air had been totally displaced from the interior of the hull was tom up and pushed out through an aperture. This left the gas in direct contact with the aluminum envelope. The airship had three propellers, two on side brackets and the third between the gondola and the hull, and since it had no rudder, it was steered by this propeller arrangement. In its second flight on Nov. 3, 1897, the belting driving the propellers slipped oif the pulleys and the helpless airship was dashed to the ground by a strong wind and wrecked.

Brigadier General Ferdinand Zeppelin devoted himself to to the study of aeronautics. In 1894 the German government rejected his proposals for a lighter-than-air flying machine. Although now aged sixty, Zeppelin decided to invest his own money in a company producing airships. By 1898 Zeppelin, with a team of 30 workmen, had assembled his first airship. The main principle of Zeppelin's invention was that hydrogen-filled gas-bags were carried inside a steel skeleton.

Zeppelin flew the world's first untethered rigid airship, the LZ-1, on 02 July 1900, near Lake Constance in Germany, carrying five passengers. The cloth-covered dirigible, which was the prototype of many subsequent models, had an aluminum structure, seventeen hydrogen cells, and two 15-horsepower (11.2-kilowatt) Daimler internal combustion engines, each turning two propellers. The airship, which weighed 12 tons, was about 420 feet (128 meters) long and 38 feet (12 meters) in diameter and had a hydrogen-gas capacity of 400,000 cubic feet (11,300 cubic meters). During its first flight, it flew about 3.7 miles (6 kilometers) in 17 minutes and reached a height of 1,300 feet (390 meters). However, it needed more power and better steering and experienced technical problems during its flight that forced it to land in Lake Constance. After the Zeppelin LZ made its first flight, the German government decided to help fund the project. After additional tests conducted three months later, it was scrapped.

Zeppelin flew the world's first untethered rigid airship, the LZ-1, on 02 July 1900, near Lake Constance in Germany, carrying five passengers. The cloth-covered dirigible, which was the prototype of many subsequent models, had an aluminum structure, seventeen hydrogen cells, and two 15-horsepower (11.2-kilowatt) Daimler internal combustion engines, each turning two propellers. The airship, which weighed 12 tons, was about 420 feet (128 meters) long and 38 feet (12 meters) in diameter and had a hydrogen-gas capacity of 400,000 cubic feet (11,300 cubic meters). During its first flight, it flew about 3.7 miles (6 kilometers) in 17 minutes and reached a height of 1,300 feet (390 meters). However, it needed more power and better steering and experienced technical problems during its flight that forced it to land in Lake Constance. After the Zeppelin LZ made its first flight, the German government decided to help fund the project. After additional tests conducted three months later, it was scrapped.

Zeppelin continued to improve his design and build airships for the German government. In June 1910, the Deutschland became the world's first commercial airship. The Sachsen followed in 1913. Between 1910 and the beginning of World War I in 1914, German zeppelins flew 107,208 (172,535 kilometers) miles and carried 34,028 passengers and crew safely.

The LZ-3 Zeppelin was accepted into army service in March 1909. By the outbreak of the First World War the German Army owned seven of these airships. A total of eleven Zeppelins were in commission at the outbreak of the war; there were seven military (Z-2 to Z-8), one naval (L-3) and three-passenger airships (Sachsen, Hansa and Viktorio-Luise). The Zeppelin developed in 1914 could reach a maximum speed of 136 kph and reach a height of 4,250 metres. The Zeppelin had five machine-guns and could carry 2,000 kg (4,400 lbs) of bombs. During the war, Hugo Eckener, a German aeronautical engineer, helped the war effort by training pilots and directing the construction of zeppelins for the Germany navy.

During the war, the Germans used zeppelins as bombers. Zeppelins could deliver successful long-range bombing attacks, but were extremely vulnerable to attack and bad weather. The airships could approach their targets silently, and initially could fly at altitudes above the range of British and French fighters. However, they never became effective offensive weapons.

In the early part of the war Zeppelins were used for bombing raids. A Zeppelin bombed Liege in Belgium on 6th August, 1914 but was forced to land after encountering artillery-fire. Three more Zeppelins were destroyed by ground forces over the next two weeks. Although easy to hit, the Germans continued to use them on attacks on France. In January 1915, two Zeppelin navel airships 190 metres long, flew over the east coast of England and bombed great Yarmouth and King's Lynn.

The first Zeppelin raid on London took place on 31st May 1915. The raid killed 28 people and injured 60 more, and other bombing raids on London and Paris followed.. Many places suffered from Zeppelin raids included Gravesend, Sunderland, Edinburgh, the Midlands and the Home Counties. By the end of May 1916 at least 550 British civilians had been killed by German Zeppelin.

Zeppelins were used at Verdun but four were brought down by ground-fire. This brought an end to their use over the Western Front, but they continued to bomb England. British fighter pilots and anti-aircraft gunners became very good at bringing down Zeppelins. New planes with more powerful engines that could climb higher were built, and the British and French planes also began to carry ammunition that contained phosphorus, which would set the hydrogen-filled zeppelins afire. Several zeppelins were also lost because of bad weather, and 17 were shot down because they could not climb as fast as the fighters. The crews also suffered from cold and oxygen deprivation when they climbed above 10,000 feet (over 3,000 meters).

With reference to the Zeppelin airships, the L.3 type represents pre-war design, the first ship of the series being completed just before the war. This type had a long cylindrical hull of poor aerodynamical shape, cellular rudders and elevators of high resistance, and four propellers mounted on outriggers on the sides of the hull which were driven through bevel gear shafts leading to the cars in which the engines were housed.

With reference to the Zeppelin airships, the L.3 type represents pre-war design, the first ship of the series being completed just before the war. This type had a long cylindrical hull of poor aerodynamical shape, cellular rudders and elevators of high resistance, and four propellers mounted on outriggers on the sides of the hull which were driven through bevel gear shafts leading to the cars in which the engines were housed.

While this type was in production the Zeppelin Co. built the first ship of an experimental type, the Z.XII, in which an effort was made to reduce the large amount of head resistance offered by the cellular control surfaces and the propeller drive. The control and stabilizing surfaces were combined in a cruciform tail and the forward outriggers were suppressed, the forward engine being made to drive, tnrough a gear box and a disc clutch, a single propeller fitted at the end of the car. The performance of this experimental type was so conclusive that when the authorities required the laying down of a type embodying a larger useful load, higher speed and higher ceiling, the Zeppelin engineers decided to adopt the new propeller drive and the cruciform tail for the new ships.

At the same time it was realized that the performance could still be improved by giving this type a smaller fineness (length/ diameter) ratio and so it came about that the first war production type, the L.10, was only a few feet longer than the preceding type, whereas its diameter was 12 feet larger. The fineness ratio was thus reduced from 10.0 to 8.8 and the performance, owing to the better streamline of the hull, was notably improved. The outrigger propeller drive was retained for the rear car, but this now housed three engines, one of these driving a stern propeller, and another stern propeller was mounted in the forward car. When, in the summer of 1915 the new Maybach 240 hp. engine became available, it was substituted for the old 210 hp. type, resulting in a slight increase in speed of these ships.

Before the close of 1915 a new problem came up, however. The greatly improved climbing ability of the Allied airplanes and the greater accuracy of anti-aircraft guns now made it imperative for the German airships not only to climb higher than heretofore, but also to climb faster. The naval nnd military authorities of Germany therefore demanded a greater margin of useful load to allow for carrying extra ballast. The Zeppelin engineers temporarily solved the problem by adding a gas cell to the L.10 type, whereby the useful load was increased by about a ton and a half. The resulting L.20 type was, however, soon to be replaced by a vastly improved vessel and when this made successful trials, the production program of the L.20 type was stopped with the sixth vessel of the series, which was then in process of construction.

The method of the Zeppelin engineers in the development of their airships was to construct a given type of airship, and when all information had been gained from it, cut it in two, insert an extra gas cell, and experiment with the lengthened ship. The next step was a redesign, either keeping the same number of gas cells or reducing them, and at the same time increasing slightly the length of ship and the horsepower, and, less frequently, increasing the diameter. The new product then is used exactly like its predecessor, and gradually better constructional features are developed and incorporated.

1 cubic meter = 35.3146667 cubic feet 22,500 m³ = 800,000 ft³ Bodensee 50,000 m³ = 1,800,000 ft³ 60,000 m³ = 2,100,000 ft³ 100,000 m³ = 3,500,000 ft³ 135,000 m³ = 4,767,000 ft³ 22,500 m³ = 426 ft Bodensee 50,000 m³ = 520 ft 60,000 m³ = 545 ft 100,000 m³ = 620 ft 135,000 m³ = 666 ft L16 = LZ50 L30 = LZ62 L49 = LZ96 L57 = LZ102 L59 = LZ104 L71 = LZ113 L71 = LZ114 LZ-1 LZ-4 Length 128m 136m 420' 446' Diam 11.7m 13m 38.5' 42.5' gas 11,300m3 15,000m3 |

First the number of engines was reduced to five, the stern propeller of the after car being dispensed with together with its engine. Then, on another type, the outriggers were also suppressed so that the number of propellers was reduced to three, that is, one astern of the forward car and two on wing cars. The latter were however fitted with two engines each, either or both of which could drive the propeller through a suitable gear box and clutch arrangement. This scheme, which was intended to provide for emergencies, proved so satisfactory that the principle was incorporated in the final design of the modified L.30 (or L.48) type. In the latter there were four propellers disposed In a quadrilateral, two being in the center line and two in wing cars, and the rear main car housed two engines, one to be used for emergencies. The saving in head resistance which the suppression of the outrigger propellers represented enabled these ships to have a much better performance than the L.30 type, although their power plant was smaller. The great reluctance the Zeppelin engineers displayed in parting with the outrigger drive may be understood when it is known that this system was their own invention, whereas the wing cars had been originated by the rival Schutte-Lanz firm, which has used this drive on all of its ships ever since 1914.

The next step in improving the L.30 class consisted in generally lightening the construction. Thus the stern was deprived of its gas bag, it being deemed that the lift derived from it was out of proportion to its weight. Then, in the summer of 1917, came a much more radical innovation. The L.48 type, or L.30 type with the standard propeller drive, was entirely redesigned in detail, as a result of which the length of the gas cells was increased from 33 feet to 49 feet and their number was reduced from 18 to 14. The saving in dead weight amounted to a ton and the ceiling of the ships was improved in proportion, while maneuvering became more convenient owing to the lesser number of gas bag controls. Against this advantage was the drawback that the hull, having now two intermediate transverse girders between the main, stress-taking, frames, proved less resistant than the old design and required frequent overhauling. The introduction of a new high resistance aluminum alloy only partly solved this problem.

Another danger against which the Zeppelin engineers had to provide in this L.53 type was the surging of the gas against the high side of the ship or against the wire wall of a gas cell that might accidentally become deflated. To provide against this contingency, which might have serious consequences owing to the large amount of gas contained in each bag- about 200,000 cubic feet in those located in the parallel portion of the hull - each gas bag was not only securely fastened to the framework by wires, but it was also internally trussed by radial wires.

Having reduced the number of gas cells in the improved L.30 type, the Zeppelin engineers were once more at liberty to increase its size for special requirements by the addition of further gas cells. Thus in the L.57 type, which was produced for special long range scouting, the capacity was increased to 2,400,000 cubic feet and the useful load to over 52 tons, with a corresponding decrease in speed and ceiling. Only two ships of this type were built, one of which made a 4,500-mile flight from Yamboli, Bulgaria, to the Soudan and return in an attempt to deliver 12 tons of medical supplies to the German forces in East Africa. Before the airship could reach its destination, however, it was recalled by a radio, the German forces in question having surrendered in the meantime. When it landed 95 hours later it still had 64 hours of fuel remaining- enough to have flown to San Francisco had it taken a great circle route west instead of flying south. This flight was the longest non-stop voyage made by an airship to date. Nonstop flights from Bulgaria to San Francisco carrying that large a payload could not have been accomplished by a B-29 thirty years later. In 1917, it was closer to the realm of science fiction.

In the winter of 1918 it became increasingly evident that unless the German airships could show a much better speed and climb they would, one after the other, be brought down by Allied airplanes and anti-aircraft guns. In an endeavor to solve this problem the Zeppelin engineers first fitted the L.53 type with the 290 hp., or super-compressed, Maybach type engine, and later produced the L.70 type, which was the most heavily engined airship ever built. It had seven 290 hp. engines, four of which were mounted in wing cars, and developed a speed of over 77 mph, but its ceiling was already inadequate, for British aviators brought the ship down in flames in the North Sea on one of its enrly raids. The sisterships were thereupon modified by removing the reserve engine from the rear car, which increased their ceiling by 2,000 feet, and plans were laid down for the construction of a much larger series. The latter, L.100 type, was ordered before the armistice, but construction had not begun when hostilities ceased.

According to Col. William N. Hensley, Jr., in the New York World in 1919, the German General Staff made complete plans to bomb New York City from the air about Thanksgiving, 1918. He asserts that the L-72 was constructed for the raid. The L-72 measures 775 feet, and is equipped with six engines of 260 H.P. each. It was capable of carrying five tons of high explosives and incendiary material. Colonel Hensley adds: "Action for every hour and minute of the trip was foreseen, every possible contingency of weather, fuel exhaustion, damage to ship or machinery failure had been reckoned. Weather charts of the Atlantic were gathered, files of the German admiralty were combed and the records of the merchant marine searched. Three hundred and sixty-seven times the voyage was made on paper. The chances of real success were 367 to 1." By 1918, 67 zeppelins had been constructed, and 16 survived the war. A total of 115 Zeppelins were used by the German military, of which, 77 were either destroyed or so damaged they could not be used again. In June 1917 the German military stopped used Zeppelins for bombing raids over Britain and instead used them for transporting supplies.

At the end of the war, the German zeppelins that had not been captured were surrendered to the Allies by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, and it looked like the Zeppelin company would soon disappear. However, Eckener, who had assumed the company's helm upon Count Zeppelin's death in 1917, suggested to the U.S. government that the company build a huge zeppelin for the U.S. military to use, which would allow the company to stay in business. The United States agreed, and on October 13, 1924, the U.S. Navy received the German ZR3 (also designated the LZ-126), delivered personally by Eckener. The airship, renamed the Los Angeles, could accommodate 30 passengers and had sleeping facilities similar to those on a Pullman railroad car. The Los Angeles made some 250 flights, including trips to Puerto Rico and Panama. It also pioneered airplane launch and recovery techniques that would later be used on the U.S. airships, the Akron and Macon.

After the war Zeppelins were used for luxury passenger transport. The "Bodensee" was 426.4 feet (130 meters) long, after she had been lengthened by 32.8 feet (10 meters). Her diameter was 61.3 feet (18.7 meters) and she carried 794,475 cubic feet (22,500 cubic meters) of hydrogen. Her useful load normally was 25,353 pounds (11,500 kilograms). Her four motors were of 260 horsepower each. They turned three direct-driven propellers, one in each of the port and starboard motor gondolas which hung from the sides of the ship. The third propeller was driven by two engines in the rear motor gondola. The propellers averaged from 1,300 to 1,400 revolutions a minute. The "Bodensee" was capable of making 80 miles an hour. Her cruising speed was 75 miles an hour.

The Graf Zeppelin, which flew round the world in twenty days, included separate passenger cabins, lounges and dining-rooms. The construction of hydrogen-filled airships with rigid keels was abandoned after several disasters including Britain's R.101, that burst into flames over France in 1930.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|