Bosnia and Herzegovina - People

The state lacks legitimacy among all three ethnic groups: Serbs, Bosniaks, and Croats. The political agendas of their leaders increasingly reflect their respective ethnic group's wartime goals. For the Serbs, it is de facto, perhaps even de jure, separation of their Republika Srpska [RS]; for the Bosniaks, it is elimination of the entities and creation of a strong central state; and, for the Croats, it is creation of a third, Croat-majority entity. The Serbs see little to gain by giving Bosnia constitutional legitimacy, and they see much to lose in terms of the autonomy and territorial security the RS now enjoys.

The state lacks legitimacy among all three ethnic groups: Serbs, Bosniaks, and Croats. The political agendas of their leaders increasingly reflect their respective ethnic group's wartime goals. For the Serbs, it is de facto, perhaps even de jure, separation of their Republika Srpska [RS]; for the Bosniaks, it is elimination of the entities and creation of a strong central state; and, for the Croats, it is creation of a third, Croat-majority entity. The Serbs see little to gain by giving Bosnia constitutional legitimacy, and they see much to lose in terms of the autonomy and territorial security the RS now enjoys.

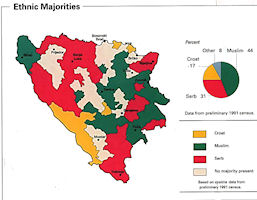

An important factor in Bosnia-Hercegovina is the distribution of the various nationalities, none of which are neatly confined to any particular area. Of 109 districts (opstina), twenty-six have no one nationality in the majority. Generally speaking, Muslims are in the majority in the far northwest corner of the republic, around the cities of Bihac and Prijedor, as well as in the center of the republic and eastward to the border with Serbia. Serbs comprise majorities in many of the northwestern regions (from the northern border with Croatia through the city of Banja Luka to the southern border with Croatia), in the far south (around the city of Trebinje and the border with Montenegro) and in a few areas in the central and north-eastern regions of the republic. Croats live predominantly in the region along the southern border with Croatia between the towns of Livno and Neum, as well as in a few central areas and along the northern border with Croatia. With few exceptions, Muslims are the second largest group in districts dominated by the other nationalities.

The diverse population of Bosnia-Hercegovina is a reflection of continuous historical changes. Settled by south-migrating Slavs in the first millennium, the region that is today Bosnia-Hercegovina fell on the European dividing line between the eastern and western Roman empires and then the Frankish empires and Byzantium. In medieval times, the region was dominated by, or part of, the Byzantine Empire and the Serbian kingdom in the south and east, and briefly by the small Croatian state that was eventually dominated by Hungary to the north and west, hence the large Serbian and Croatian populations today.

While Bosnia derives its name from the Bosna river running virtually through the center of the republic, Hercegovina received its name when Hungary formed it as a duchy ("herceg"meaning "duke" in Hungarian). In some regions of the current republic, smaller states with varying degrees of independence temporarily formed, especially under Ban Kulin in the late 12th century and the Kotromanic dynasty of the 14th and 15th centuries. Both of the latter were influenced strongly by a religious movement called the Bogomil heresy, which was viewed as a threat and therefore suppressed as much as was possible by both Byzantium and Rome.

In 1463, the Ottoman expansion into Europe led to full Turkish domination of both Bosnia and Hercegovina. The Bogomil church faded as much of the local population converted to the Islamic faith of the new overlords. In addition, a number of the Orthodox Serbs from the region, fleeing Ottoman Turk encroachments and encouraged by the Habsburgs, moved northward, some traveling as far as regions which are now part of Croatia.

After approximately four centuries of uninterrupted Ottoman rule, during which Bosnia-Hercegovina occupied borders close to those existing today, the Balkan revolts which marked the steady decline of the Ottomans led to Bosnia-Hercegovina being placed under Austro-Hungarian administration in 1878. In 1908, Bosnia-Hercegovina was annexed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, an act which fueled local na- tionalist resistance encouraged by Serbia, which hoped to gain control of the region. This resistance even- tually led to the June 1914 assassination of the Habsburg Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, a member of the secret "Young Bosnia" organization, setting off the chain of events which quickly led to World War I.

Following the Great War and the consequent fall of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires, Bosnia-Hercegovina, along with other South Slav regions, united with Serbia to create the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1918, renamed Yugoslavia in 1929. During World War II, Bosnia-Hercegovina was made part of the independent and fascist Croatian state and was the scene of considerable internecine warfare until the communist Partisans, under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito, liberated the country from foreign occupation.

Bosnia-Hercegovina was at the center of every Yugoslav doomsday scenario. It was Yugoslavia's killing ground in World War II, with Croatian Ustase and Muslim guerrillas battling Communist Partisans and Serbian Chetniks in a vicious three-cornered struggle. A negotiated division of Bosnia-Hercegovina would permit the Serbs and Croats to satisfy their ambitions and leave the Muslims to choose between joining Croatia or forming a Muslim state in what would be left of Bosnia-Hercegovina. This would be extremely difficult to achieve, given the republic's patchwork ethnic distribution. Even assuming that all of the players have the best intentions, it could not be carried out without extensive population shifts.

In Bosnia-Hercegovina, concern over balancing the republic's three main nationalities complicated the election process. The election law itself reflected this fact, apportioning by nationality the seats on the collective Presidency (two Muslims, two Serbs, two Croats and one from the remaining ethnic groups), and requiring the bicameral Assembly's election results to reflect ethnically, within 15 percentage points, the population as a whole. All candidates on the ballot were therefore listed according to ethnic identity in addition to party affiliation. Three main nationality-based parties played upon the sentiments of the groups they represented while uniting in their opposition to efforts by the republic's communist leaders first to block the formation of such parties and then to deny them permission to monitor the election proceedings.

In the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH), the two leading Croat parties, HDZ BiH and HDZ 1990, continue to call for the creation of a Croat-majority federal territorial unit. On 6 April 2013, these parties used the platform of the Congress of the Croat National Assembly (an informal grouping of Croat parties) to repeat such calls and to announce mechanisms for compelling elected Croat representatives to implement the decisions of this grouping of parties.

Before the war, apart from some big towns like Sarajevo, Mostar or Banja Luka, the major part of the settlement was rural: a lot of remote hamlets surrounding a mosque, a catholic or an orthodox church. Life there was difficult and hard, especially during the winter season, but these small communities survived, thanks to the solidarity of the villagers. Self-sufficiency prevailed through local agriculture and cattle breeding.

Almost four years of war totally changed this landscape. Even though the three parties (Bosniacs, Bosnian-Croats and Bosnian-Serbs) were of the same ethnicity, the ethnic cleansing they all practised as a strategy drove a large part of the population to flee from their houses, their villages and their areas of settlement. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) assessed that, by the beginning of 1996, about one million Displaced Persons were spread out all over the country, while 1.2 million were Refugees abroad. Of course, this movement strengthened the urban population to the detriment of the rural one.

A lot of people of course returned to their pre-war homes. Nevertheless, by Aug. 1, 2001, UNHCR's figures establish that nearly 700,000 Bosnians are still Displaced Persons and Refugees (DPREs). Almost 500,000 persons had the status of Displaced Persons, and a little bit more than 200,000 are still Refugees, mainly in FRY (144,000). It was the hope of the International Community that the improvement of the overall situation in FRY would encourage more and more people to return.

Those horrific figures must be compared to the pre-war population in BiH. A census carried out in 1991, one year before the war, established that the overall population of this country was 4.4 million. That means that one inhabitant in two, just at the end of the war, was not living in his pre-war home but elsewhere. Despite all the efforts and the positive trend observed over the last two years, the situation will never be the same as before the war.

An estimated 12,000 persons remain missing from the 1992-95 war. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported 22,451 requests to trace relatives missing from the 1992-95 conflict. By the end of 2009 a total of 11,399 persons had been accounted for, including 467 located alive.

The state-level Missing Persons Institute (MPI) accounts for persons missing from the 1992-95 conflict. During 2009 the Republika Srpska continued to support an entity-level body with similar responsibilities to MPI. Observers characterized the team as an effort to disrupt the MPI's work. Republika Srpska operational teams refused MPI personnel access to archives that were transferred to MPI's ownership in accordance with the law. Republika Srpska prosecutors did not cooperate in MPI's exhumation and identification process. Since May there were no exhumations or identifications carried out by Republika Srpska prosecutors.

By the end of 2009 excavations coordinated by MPI resulted in the recovery of 218 bodies and 346 sets of partial remains. The majority of remains were recovered from 13 mass graves (four of them related to the 1995 Srebrenica genocide). From 2000 through the end of 2009, the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP) generated a total of 27,505 DNA matches relevant to 15,331 missing persons, of which 23,562 DNA matches related to the country. ICMP collected over 87,766 blood samples from persons related to 28,911 missing individuals, of which 69,532 blood samples related to 23,279 persons relevant to the country.

As of the end of 2012, it was still hosting around 103,000 IDPs. Not all returnees have achieved a durable solution. Improved security and the prospect of being able to repossess and rebuild their homes prompted many IDPs to return, but many have experienced continued security incidents and only limited access to roads, water and electricity. Many lack health insurance and struggle to access pensions and social benefits. Only around 360 people returned during 2012.

Bosnia's first census since its 1992-95 war was postponed on 23 January 2013 until October 2013 after regional governments failed to agree on how to conduct it. Preliminary census results showed Bosnia's population had dropped by nearly 13 percent since the country's 1992-95 war. Bosnia's Statistics Agency director Zdenko Milinovic said nearly 3.8 million people were registered in the country during the census. In the last census, taken in 1991, Bosnia had a population of 4.4 million made up of 43.7 percent Muslims, 31.4 percent Serbs and 17.3 percent Croats.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|