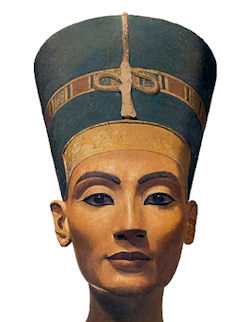

Nefertiti

Of the Egyptian queens, Nefertiti is the most famous. When seventeen-year-old prince Akhenaton inherits the throne of Egypt, his mother marries him to her fifteen-year-old niece, Nefertiti [meaning 'A Beautiful Woman has Come']. She disappeared during the last years of her husband’s reign, with just a single inscription, dated to year 16, known after year 12.

Of the Egyptian queens, Nefertiti is the most famous. When seventeen-year-old prince Akhenaton inherits the throne of Egypt, his mother marries him to her fifteen-year-old niece, Nefertiti [meaning 'A Beautiful Woman has Come']. She disappeared during the last years of her husband’s reign, with just a single inscription, dated to year 16, known after year 12.

Nefertiti was active in Akhenaten’s reign, accompanying her husband when he offered to Aten, serving in effect as the high priestess of the Aten. The Aten’s high priestess could not be buried in the precinct of Amun. Many believe that she changed her name and ruled after Akhenaten, but her tomb has never been found. Its location is one of ancient Egypt’s greatest mysteries.

In 2003, British Egyptologist Joanne Fletcherclaimed that she had found proof that the mummy of the Younger Lady found in a side chamber of the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV 35) was the mummy of Nefertiti. The Egyptian Mummy Project, using CT-scans and DNA analysis, determined that the mummy of the Younger Lady in KV 35 is very likely the mother of Tutankhamun, but her name in unknown. She was also discovered to be the daughter of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye, and Nefertiti was not their daughter.

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie argued in 1897 that the face od Nefertiti, the wife of Amenhotep IV, had much the same features as Tyi, insomuch that both were probably of the same race. And it was most probable that Nefertiti was the other name of Tadukhipa, the daughter of Dushratta, as no other queen ever appears with Amenhotep IV. This would connect Tyi with the race of Dushratta in Mitanni. In either case, we must conclude that Tyi belonged to northern Syria. Mitannian kings had Egyptian princesses, as the Egyptian kings had Mitannian princesses. Hence Nefertiti would be a rightful heiress of the Egyptian throne.

Janet R. Buttles argued that queen of Amen-hetep IV was the only one who ever appears with him as his wife. She was figured by his side in all scenes, domestic and ceremonial, and was the mother of his children. This made a difficulty concerning Tadukhipa, who was sent for from Mitanni to be the "Mistress of Egypt." But Nefertiti invariably appeared as the "Mistress of Egypt," and unless this was purely a conventional title which could be borne by two wives at the same time, it would seem that Nefertiti and Tadukhipa were one and the same person.

Amen-hetep IV., through his mother Thly, was not of royal origin ; and the traditions of his house would have pointed to the selection of a royal bride, through whom he might strengthen his claim to the throne. It has, therefore, been thought that Nefertiti was the daughter of some princess of the solar race, who was possibly a sister of Amen-hetep III. She appears with the full royal titles of the great queens of the dynasty, whose descendant she may have been.

Perhaps these two queens may be best explained by supposing Nefertiti a princess of the royal house, and Tadukhipa a secondary wife, whose position was not of sufficient rank to include her in the official sculptures of Amen-hetep IV. In this case, the invitation to become the " Mistress of Egypt" could have implied nothing more than a formal compliment.

Whether Nefertiti was then a Syrian princess or an Egyptian, it is certain that she was the beloved and honored queen of Amen-hetep IV.

The graceful figure of his consort often appears in the worship of Aten, who descends in a shower of rays upon her and her children, each ray ending in a tiny hand which rests caressingly upon them. She invariably follows the king, or sits at his side, in all ceremonial scenes; together they receive the court officials, or feast and make merry in company with their children.

The domestic life and tastes of the king are prominently brought forward, and everything that Khuenaten did, the queen and children apparently did too. In one instance, Nefertiti is depicted sitting on her husband's knee, a most unusual representation for Egyptian art. Sometimes the royal pair are shown with only one or two daughters, but as time goes on, the number increases until there are six; to this group is added a sister of Queen Nefertiti, the princess Mutnezemet.

Nefertiti had no son to succeed his father. Two of the daughters married the two succeeding kings of Egypt; while a third became the wife of a Babylonian prince, the son of King Burraburiash.

With the death of her husband, Queen Nefertiti also passes into silence, and there is no further mention of her, or of the time of her death; whether she lived on through the reigns of her two sons-in-law, or whether she died before the fall of Aten, there is nothing to show; and the end of her story, like that of so many other royal women of Egypt, remains untold.

During a 1912 Egyptian excavation, German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt discovered the bust of Nefertiti, a 14th Century BC Egyptian queen. He claimed to have an agreement with the Egyptian government that included rights to half his finds and — using this as justification — Berlin has proudly displayed the item since 1923. But a new document suggests Borchardt intentionally misled Egyptian authorities about Nefertiti, showing the bust in a poor light and lying about its composition in order to keep his most-prized find. The Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities has repeatedly asked Germany to give the bust back — or at the very least let it return home on a temporary basis.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|