Ancient Egyptian King Lists

It is inconceivable that the Egyptians, or indeed, any other people, should have attempted to register and number their kings without having any fixed point to start from. In any case the twentieth king must have been the nineteenth after number one; and for the Egyptians that number one was Menes. We see from the evidence of the Royal Papyrus and the statements of Herodotus, that such, in fact, was their chronological method. If the Egyptians had recorded only one uninterrupted line of kings, this method would have been as perfect as need be. In the way they used it, it has become a source of endless confusion.

There are lists of kings who ruled during the earlier part of the period of Egyptian history, but without definite statements in them either as to the order in which one king succeeded the other, or as to the length of each king's reign, or when the king whose name stands first in the lists began to reign. There are also lists of Egyptian kings written in Greek which are divided into dynasties, and which profess to give the number of the years of the reign of each king, and also the number of the years which each dynasty lasted; but these, like the old Egyptian lists, are not infallible.

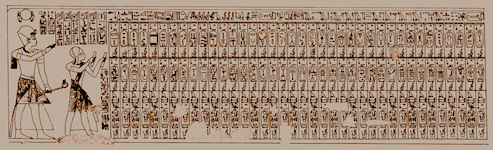

The most complete native list of kings known is contained in the famous Royal Papyrus Of Turin, which, as the name given to it indicates, is preserved at Turin. It originally formed part of the collection made in Egypt by M. Drovetti, the French Consul General in that country, which was offered for purchase to the French Government in 1818, but was declined, and was afterwards acquired by the king of Sardinia; subsequently it was sent, with other things, to Turin. The document is written in the hieratic character. The nature of its contents was first recognized by Champollion le Jeune in 1824. In 1826 Seyffarth went to Turin, and undertook to join the fragments of the papyrus together, and he formed an uninterrupted series of successive reigns, which, although restored, appeared to be an absolutely complete Royal Canon. The worthlessness of Seyffarth's "restoration" was soon recognized, as his system of Egyptian decipherment was faulty.

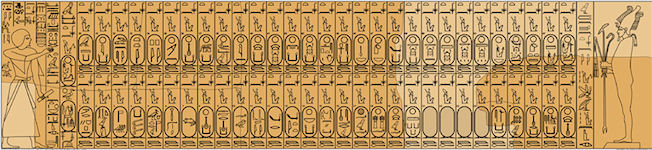

Of the greatest importance for the study of Egyptian chronology is the Tablet of Abydos, which was discovered by Dumichen in the Temple of Osiris at Abydos in 1864. Here Seti I, accompanied by his son and successor Rameses II, addresses seventy-five of his predecessors, whose cartouches are arranged in chronological order before him; the list is ended by Seti's own name. The scribe arranged in chronological order the names for which he had room in the space allotted to the list, and that he only made a selection from the names in the lists which, it may be presumed, he had before him. But it is certain that the space at the disposal of the sculptor was limited, and that he commemorated only a small number of names.

What guided him in making this selection cannot be said. Some think that he wished to commemorate only such kings as were great and glorious according to the opinion prevalent in the XIXth Dynasty, and others that the names of legitimate kings only were given. The documented reigns are official and royal, and there were definitely political and/ or religious biases. The Seti I king list hasancestors of Seti I’s lline, but excludes the names of Pharoahs who were removed for political reasons. Seti I also omitted certain rulers who were viewed as unpopular in later times.

Of less importance, but still of considerable interest, is the Tablet of Sakkara, which dates from the time of Eameses II., and contains a list of forty - seven royal names drawn up, practically, in the same order as that employed in the Tablets of Abydos.

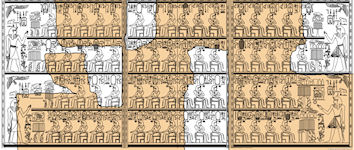

The Tablet of Karnak was discovered by Burton near the sanctuary of the great temple of AmenRa at Karnak, and dates from the period of the XVIIIth Dynasty; it contains a representation of Thothmes III adoring sixty-one of his ancestors, whose names are duly set forth in cartouches above their figures. Half of the kings face one way, and half the other, but the cartouches are not arranged in chronological order; this list, like others, does not give a complete series of the predecessors of Thothmes, and again it is not evident on what principle the selection of the names of the kings was made. The great value of the list consists in the fact that it gives the names of many kings of the XIth, XIIIth, XIVth, XVth, XVIth, and XVIIth Dynasties, and thus supplies information which is wanting in the Tablets of Abydos and Sakkara.

Next to the lists of kings drawn up in hieroglyphics must be mentioned the famous List of Kings which was divided into dynasties, and which formed part of the great historical work of Manetho on ancient Egyptian history. It is to Manetho that is owed the word dynasty as applied to Egyptian history. This distinguished man was born at Sebennytus, and he flourished in the reigns of Ptolemy Lagus and Ptolemy Philadelphus; his name seems to be the Greek form of the Egyptian Ma-en-Tebuti, i.e., "gift of Thoth". In the third century BC, Manetho, writing in Greek, produced a history of his native country.

No version of Manetho’s original manuscript has yet been found, but four sources claim to be based on his writings. They are found in the famous "Chronography," which was drawn up about the end of the VIIIth century by George the Monk, the Syncellus of Tarasius, Patriarch of Constantinople, and which professed to give an abstract, with dates, of tbe history of the world from Adam to Diocletian. The oldest version of Manetho is made known an extract from the Chronicle of Julius Africanus, a Libyan who flourished early in the IIIrd century AD, which is preserved in the Chronicle of Eusebius (born AD 264, died about 340), Bishop of Caesarea; the version given by Eusebius contains many interpolations; and that preserved in the Armenian rendering of his works is considered by some to be the more correct. Besides the versions of Africanus and George, commonly called Syncellus, there is another known as the "Old Chronicle," and still another which is called the "Book of the Sothis."

Unfortunately, not only are all these sources often wildly inconsistent with each other, especially as regards the Second Intermediate Period, they are often very much out of synch with the archaeological record. Manetho’s Eighteenth Dynasty provides a good illustration of the many problems associated with his dynastic chronology. While clearly based on some accurate ancient records concerning the kings of that dynasty and the lengths of their reign, the record as it has been preserved contains many errors. It lists more kings than actually served; his Greek transliterations don’t always easily correspond to recognizable Egyptian names; to the extant some kings are identifiable, they are listed out of order; there is confusion over the name of the dynasty’s first king; and it includes Sethos and Ramesses in the Eighteenth Dynasty, giving the former an improbably long reign of 59 years.

An examination of the versions of Manetho's King List according to Julius Africanus and Eusebius shows that they do not agree in many important particulars, i.e., in arrangement of dynasties, in the lengths of the reigns of the kings, and in the total numbers of kings assigned to the different dynasties. Moreover, according to Julius Africanus 561 kings reigned in about 5524 years, while according to Eusebius only about 361 kings reigned in 4480 or 4780 years. In the Old Chronicle the total number of kings given is 84, and they are declared to have reigned about 2140 years, and in the Book of the Sothis the total number of kings is 86 and the total duration of their reigns is given as about 2500 years. Now the information which we have obtained from the Egyptian monuments shows that the Old Chronicle and the Book of the Sothis are quite useless for chronological purposes, because it is self-evident that they do not contain complete lists of the kings, and that the names of the kings which are in them, as well as some of the dynasties, are out of order. This is a statement of fact and not a conjecture.

The version of Julius Africanus is clearly the more accurate of the two, because it agrees best with the monuments, and Bunsen was probably right in saying1 that his object was not to arrange a system of Annals, but to give the traditions unaltered, and just as he found them. In fact, judging only by the mere forms of the kings' names which he gives, and which (even after the lapse of 1600 years, and in spite of the ignorance and carelessness of subsequent copyists) are on the whole remarkably correct, it seems pretty certain that he must have had a copy of Manetho's list before him. The version of Eusebius was based upon that of Africanus, and he appears to have been careless in copying both names and figures, and the names of many kings are wanting in the extant copies of his works.

Plutarch relates that Manetho was a high-priest and scribe connected with the mysteries in the temple of Heliopolis, and there is no doubt that, in compiling the work which he had received the royal command to undertake, he would be in a position to draw his information from sources which were regarded as authoritative and authentic by his brother priests. That his name carried weight, and that his reputation for learning was very great for centuries after his death, is evident from the fact that impostors endeavoured to obtain circulation for their own pseudo-historical works by issuing them under his name.

When Manetho was directed by Ptolemy Philadelphia to write the history of Egypt, how came it that he was able to multiply so enormously as he did, the number of kings, extending the monarchy backward from the time of Alexander the Great through thirty dynasties, and the space of above 5300 years? His motive for such amplification may be easily traced to national vanity; but where were his means? Let it be recollected that at the time Egypt abounded with records which could neither be effaced nor concealed, and that if the Egyptian high-priest had attempted to falsify them in a palpable manner he must have been detected.

Manetho's contemporaries would have taken care to expose an attempted falsification; and the inevitable consequence must have been severe punishment, for Ptolemy would never have suffered a manifest imposition practised on him to escape with impunity. But when it is considered that the names in those records were ideagraphically written, and when the nature of that writing is taken into account, then the difficulty is completely removed. Indeed it is most likely that Manetho himself was not aware of the full extent of his deviation from the truth; and even if he was, there was no way for others of detecting this, and proving it against him. No doubt he had many kind friends anxious to relieve him from the cares of office, and to—step into his place.

The next authority after Manetho is Eratosthenes. He was keeper of the Alexandrean library in the reign of Ptolemy Euergetes, the successor to Ptolemy Philadelphus, in the second half of the third century BC. Among the few fragments of his works which reached modern times, transmitted through the Greek historians, is a catalogue of thirty-eight or thirty-nine kings of Thebes, commencing with Menes (who is mentioned by the other authorities also as the first monarch of Egypt), and occupying by their successive reigns 1055 years. These names are stated to have been compiled from original records existing at Thebes, which city Eratosthenes visited expressly to consult them. The names of the first two kings of the first dynasty of Manetho are the same with those of the first two kings in the catalogue of Eratosthenes ; but the remainder of the catalogue presents no farther accordance, either in the names or in the duration of the reigns.

Herodotus - "the father of history" - flourished about BC 450, and visited Egypt, about the middle of the fifth century before Christ. For Egypt, Herodotus distinguishes a space of "less than 900 years" between his own time and the death of Moeris, "the earliest king who did anything to be recorded." But he fails to make out any connected account of the eight or nine centuries so specified. His consecutive notices of Egyptian history begin only with the Saite kings who, in the 7th century before Christ, first engaged a corps of Greek mercenaries, and opened the Canopic mouth of the Nile to Greek traders. Some 330 or 331 kings were rightly named to Herodotus as having reigned from Menes to Sesostris (Sesostris here being Rameses III.), but that their years when added up together instead of being above 11,000, as Herodotus supposed, reckoning each king as a full life-generation, were in all only 3750. Before Sesostris, and his predecessor Moeris, he has a fable of 330 generations of kings in lineal succession, who were all faineants, but who reigned, as he supposed, or as he was given to understand, during a space of above 11,000 years.

Some time before Herodotus, Hippys of Rhegium and other travellers had visited Egypt. Among these Hecatsus of Miletus is the most conspicuous. He travelled thither about the 59th Olympiad, and described particularly the upper part of Egypt, bestowing especial attention on the state or city of Thebes, and the history of its kings. Hence the reason why Herodotus says so little on these points.

Next to Herodotus, Manetho, and Eratosthenes, the most important authority, in relation to Egypt and its institutions, is Diodorus Siculus, who lived under Caesar and Augustus, and who, independent of his own observations and his researches on the spot, refers frequently to the old Greek historians, and particularly to Hecatams of Miletus, after whom he describes the ancient kingdom of Thebes, and gives an account of the monuments of this famous city, with surprising fidelity.

The Cheops of Herodotus, is the Sophis of Manetho, and Saophis of Eratosthenes.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|