Bangladesh - Bengali Language

Bengali is the language of over two hundred million people, of whom a third live in West Bengal and Tripura, a few millions in the neighbor states within India, especially in the Cachar district of Assam, and the bulk in Bangladesh. It is one of the fourteen national languages of India, and was one of the two of Pakistan prior to the 1971 Liberation War. It is used as medium of instruction up to the postgraduate level in the humanities and up to the junior college level in the natural sciences. It is used for religious purposes only as subsidiary to Sanskrit for Hindus, and to Arabic for Muslims. There is great attachment to and pride about the language, about the literature, and even about the script, shared alike as these are across the political and religious divisions.

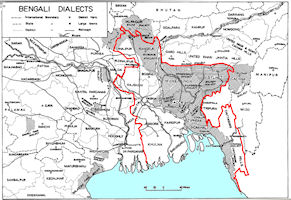

Other languages also spoken in the area are chiefly Hindi-Urdu and English, each spoken almost wholly in urban areas, where each is also just as adequate for most purposes of life as Bengali is. In West Bengal alone, 276 newspapers were published in 1963 in English, 93 in Hindi, and 25 in Urdu, in comparison to 513 in Bengali. Also spoken are Nepali in the Darjeeling district of West Bengal, Santali near the western boundaries of West Bengal, and various tribal languages distantly related to Tibetan and Burmese in Tripura, in the Darjeeling district of West Bengal, and in the Chittagong Hills of East Pakistan. Calcutta is the largest city, with a population of over 4.5 million, and has many relatively isolated linguistic communities, one of the largest of which speaks Oria.

The Bengali script is historically derived from the ancient Indian Brahmi, itself a modification of ancient southern Arabic, along a line of development a little different from that of the Devanagari. The script used for Assamese differs by two additional letters only, and those used for Manipuri and Maithili are fairly closely related to this script. The systematic features are as follows. It goes from left to right, but quite unlike Roman, hangs from the line. It also uses upstrokes as often as downstrokes, and prefers sharply reversed angles as often as looped or arched angles. There are no capitals, and the punctuation system is almost wholly taken from English. It is a syllabary, somewhat modified towards becoming an alphabet, and uses diacritics in all four directions to indicate non-initial vowels and some consonants.

The Bengali script is historically derived from the ancient Indian Brahmi, itself a modification of ancient southern Arabic, along a line of development a little different from that of the Devanagari. The script used for Assamese differs by two additional letters only, and those used for Manipuri and Maithili are fairly closely related to this script. The systematic features are as follows. It goes from left to right, but quite unlike Roman, hangs from the line. It also uses upstrokes as often as downstrokes, and prefers sharply reversed angles as often as looped or arched angles. There are no capitals, and the punctuation system is almost wholly taken from English. It is a syllabary, somewhat modified towards becoming an alphabet, and uses diacritics in all four directions to indicate non-initial vowels and some consonants.

Spelling is fairly well standardized. There are, however, some marginal indeterminacies, and this due to four reasons. One is that a large and increasing number of borrowings are taking place from English, and these cannot be provided with unique transcriptions in the Bengali orthograhy. Another isthat words have been borrowed into the standard from differentdialects of Bengali. Still another is that words taken from Sanskrit may often be spelt in alternative ways even according to the standard Sanskrit grammar. Finally, non-Sanskrit words of folk origin had until recently no common written shapes and so have to depend on the not very phonemic orthography alone for their spellings.

Standard Bengali is not, however, perfectly uniform. There are two standards, Chalit and Sadhu. The former is now the dominant one. In both standards a few peculiarities occur in the usage of some but not all Muslims. In the Chalit,the main historical contributor has been the speech of Hooghly and Krishnagore, small towns along the river somewhat north of Calcutta. It is not however the only ingredient, and many Chalit forms are traced to contributions by other dialects. In the Sadhu, the dominant, though by no means the only contributor had been the speech of late 15th century Navadvip, a center of learning a little farther north along the river.

The history of the Bengali language begins in the early centuries of the second millenium. Before this time, there was only a family of dialects of the common eastern Indian prakrit. The Indo-Aryan languages fall into four distinct periods. In thefirst period, Vedic was the common standard. In the second, it was classical Sanskrit. In the third, there were many prakrits. And in the fourth, it is the modern standard languages. Within the last period, again, two phases are distinguished for Bengali. These various standards are directly related to one another in the line of cultural succession, but in terms of linguistic structure are only indirectly related through a common matrixof folk speech. One has not grown or decayed into the other, but each has been an attempt to create a uniform ideal out of the diverse and unstable speech of the people. The Chalit is now widely spoken, at least by all who have been to college.

Of the substandard dialects, the Dacca dialect is important, firstly, because it is the main ingredient in the speech to be heard in and around Dacca, the capital of Bangladesh, and secondly, because it is rather closely related in formal structure to the dialects of the larger part of Bengal, including large areas in India. In and around Dacca, three quite different varieties of Bengaliare heard. The Chalit itself, standard modern Bengali, is spoken much the same as in Calcutta, but only within the college educated upper and middle classes. The older resident lower classes in Dacca city speak pidgin Urdu and a kind of Bengali known as Kutti ['belonging to the fort']. The lower middle classes around, and partly in Dacca, speak what is labelled the Dacca dialect, though this is far less uniform in usage than a brief description will suggest. The Dacca dialect happens to be mutually intelligible with the dialects of the greater part of East Pakistan and large areas of West Bengal.

Of the substandard dialects, the Dacca dialect is important, firstly, because it is the main ingredient in the speech to be heard in and around Dacca, the capital of Bangladesh, and secondly, because it is rather closely related in formal structure to the dialects of the larger part of Bengal, including large areas in India. In and around Dacca, three quite different varieties of Bengaliare heard. The Chalit itself, standard modern Bengali, is spoken much the same as in Calcutta, but only within the college educated upper and middle classes. The older resident lower classes in Dacca city speak pidgin Urdu and a kind of Bengali known as Kutti ['belonging to the fort']. The lower middle classes around, and partly in Dacca, speak what is labelled the Dacca dialect, though this is far less uniform in usage than a brief description will suggest. The Dacca dialect happens to be mutually intelligible with the dialects of the greater part of East Pakistan and large areas of West Bengal.

The Chittagong dialect is an example of an extremely deviant dialect. Some of the other highly deviant dialects are Chakma along the Karnaphuli river in the Chittagong Hills, Sylhet, Hajong in northern Mymensingh and Sylhet, Rajbangshiin Rangpur - these in East Pakistan; Malpaharia in the Santhal Parganas, Kharia Thar in the areas south west of Ranchi - these in Bihar; the Kaivarta speech in central Midnapore in West Bengal.

In linguistic relationship, Bengali is closest to Assamese, then to Oriya, then to Hindi. The latter resemble each other somewhat more closely than Bengali, so that Bengali is regarded as the most recent and the most divergent of the eastern Indo-Aryan group of languages. Bengali is not, however, unmixed Indo-Aryan. The general structural patterns show numerous striking resemblances to the Dravidian languages of southern India. Many isolated words have been traced to Austro-asiatic (which includes Cambodian and Vietnamese), to Tibeto-Burman (which includes Tibetan, Burmese,and Thai), to Arabic, Turkish, Persian, and Portuguese. About 60 percent of the word types in formal Bengali are classical Sanskrit, and about 15 percent of the word types in informal Bengali are British English.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|