Chapter Nine Analyzing Chinese Military Expenditures

Richard A. Bitzinger

|

Seek truth from facts. |

Consequently, it is not surprising that China watchers in the West are keen to know more about Chinese defense spending. As China looms ever larger in the Western, and particularly U.S., security calculus, concerns over China as an actual or potential military challenge have grown correspondingly. One important piece of the China threat puzzle is understanding where current Chinese strategic and military priorities lay, and whether the Chinese are investing sufficient resources in these priorities to constitute a serious security concern for the West.1 So just how much is China spending on its military? The question is simple, perhaps, but it is one that has increasingly preoccupied and perplexed Western China watchers, not to mention their governments and militaries. Moreover, it is particularly prominent every March, when Beijing releases its defense budget for the next year. In early 2001, for example, China reported that it would spend 141 billion yuan ($17 billion) on the People's Liberation Army (PLA)--an increase of 17.7 percent over the previous year and continuing a 12-year trend of real growth in Chinese military expenditures. Likewise, given China's inflation rate of practically nil, this increase constituted its largest real rise in defense spending in more than a decade. Not surprisingly, this announcement unleashed a flurry of speculation as to what the budget says about China's strategic intentions and its future military plans and whether its expanse translates into a growing Chinese threat to the West--particularly the United States and its friends and allies in East Asia. Beijing further fanned the flames by asserting that the increase in defense spending was necessary in order "to adapt to drastic changes in the military situation of the world and prepare for defense and combat given the conditions of modern technology, especially high technology."2 On top of this, analysts widely accept that the official budget released by the Chinese every year accounts for only a fraction of actual defense spending. In particular, whole categories of military expenditure are believed to be missing from official figures, seriously undervaluing real PLA spending and reinforcing beliefs that Beijing's lack of candor and transparency regarding its defense budget is yet another indicator of its aggressive and irredentist intents. At the same time, Western attempts to fill in the gaps in Chinese military expenditures--however much they are good-faith efforts to be scientific and "reasonable"--still largely consist of guesswork and hence contain a considerable margin of error. In addition, such estimates vary widely from each other, which have only further clouded the whole issue of analyzing and assessing Chinese defense spending. Consequently, Western efforts at Chinese defense budget analysis have reached a methodological dead end. The salient issue now is, where do we go from here? In this regard, this essay has two purposes. First, by discussing what we do and do not know--and, more importantly, what we will probably never know--about Chinese military expenditures, it attempts to determine the limits to using defense budget analysis as a research tool for inferring and evaluating Chinese military priorities, policies, strategies, and capabilities. Second, it offers some suggestions and alternative approaches for improving and reinvigorating this line of research, including offering at least one approach for assessing likely future Chinese procurement costs and expenditures. In particular, this essay recommends that we get away from simply focusing on making bottom-line assessments and rather attempt to link military capabilities and requirements to budgetary demands to determine if there is a spending-capabilities mismatch.

What Do We Want Defense Budgets to Tell Us?What insights do we hope to get from analyzing defense budgets and military expenditures? Ideally, such analysis should inform us better as to:

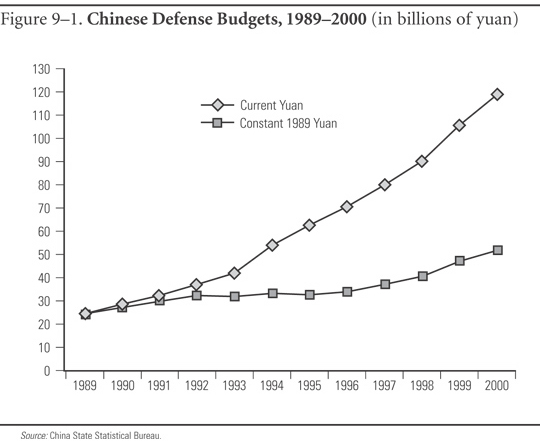

Facts and Assumptions about Chinese Military ExpendituresWe can utilize defense budgets to see if (and where) a country is putting its money where its mouth is concerning national security and defense. As such, the strength of defense budget analysis is its use of hard, empirical information--such as fiscal authorizations, appropriations, and outlays--that can be quantified and charted. This information, in turn, can be compared, tracked, and trend-lined over time and subjected to a variety of statistical analyses. Thus, it can reveal insights into a country's plans, priorities, and likely capabilities. However, before we can use defense budgets and military expenditures to address such quantifiable issues, we must first have the budgetary figures to work with. More than almost any other field of inquiry, defense budget analysis is a highly data-dependent field of study; in other words, it involves a lot of number-crunching. Consequently, it demands having a lot of numbers to crunch, and the more numbers we have, the more detailed (and useful) will be our analysis. Despite the need for large amounts of data, few areas of Chinese military studies actually have access to less reliable data than defense budget analysis. The issue of data--or rather, the lack thereof--is therefore the greatest obstacle to constructing useful methodologies for studying and interpreting Chinese defense spending in-depth. So what do we know? First of all, we possess a few firm facts when it comes to Chinese military expenditures and defense budgeting: We know the official topline figure for Chinese military expenditures. Every March, as part of its annual state budget, the Chinese release a single overall figure for national military expenditures. In 2001, this figure was approximately 141 billion yuan ($17 billion) while in 2000 it was 121 billion yuan ($14.6 billion). We possess similar topline figures for Chinese defense spending going back to 1950. Consequently, we can argue fairly confidently that official Chinese military expenditures have increased significantly in real terms over the past decade. Armed with reasonably reliable data regarding China's inflation rate (that is, the national consumer price index), we can estimate that, after inflation, China's official defense budget has more than doubled between 1989 and 2000 and in particular has risen 58 percent just between 1995 and 2000 (figure 9-1). In addition, recent press reports indicate that China will continue to boost defense spending with double-digit annual increases for at least the next 5 years; this would double the defense budget to $30 billion by 2005.3 From these efforts to increase military funding, we may deduce that Beijing is seriously committed to modernizing the PLA and to overcoming current personnel, equipment, and O&M-related impediments to fielding an advanced military force. We may also infer that the Chinese are using these budget increases to signal their intentions to potential adversaries--especially Taiwan and the United States--that it is serious about using military force, if necessary, to gain certain political-military objectives, such as the return of Taiwan.4 We know the official defense budget as a percentage of government spending and of China's gross domestic product (GDP). Since we have the overall figure for the annual state budget and can roughly calculate China's GDP, we can determine that during the past decade, the defense budget comprised approximately 9 to 10 percent of central government expenditures and less than 2 percent of GDP. Both figures have fallen significantly from their levels during the 1970s and 1980s, indicating that even as defense budgets are increasing, military spending is actually a declining burden on the Chinese economy. We possess a rough breakdown of official defense expenditures. According to Beijing's 1995, 1998, and 2000 defense white papers, the official defense budget is distributed almost equally among personnel, O&M, and equipment. In 2000, for example, the exact apportionment was 34 percent for personnel (40.6 billion yuan, or $4.9 billion), 35 percent for O&M (41.8 billion yuan, or $5 billion), and 32 percent for equipment (38.9 billion yuan, or $4.7 billion). In addition, Beijing has long maintained that the growth in defense spending goes mainly to raising soldiers' salaries and living conditions. In addition, we now possess data on the PLA budget for personnel, O&M, and equipment for 4 years (1997-2000). Even a cursory analysis of this data reveals some interesting facts:

Therefore, despite assertions by China that the lion's share of the recent growth in Chinese military expenditures has gone toward improving PLA soldiers' salaries and quality of life, it is clear--at least when looking only at the official defense spending figures--that procurement and O&M have benefited much more than personnel in recent budget increases.5 This could mean that the PLA is placing a higher priority on hardware or on readiness than on personnel. Alternatively, it could mean that raising living standards in the PLA is less expensive than advancing other types of modernization goals. In addition, most Western analysts of Chinese defense spending are reasonably certain that the official budget omits a number of critical expenditures, including:

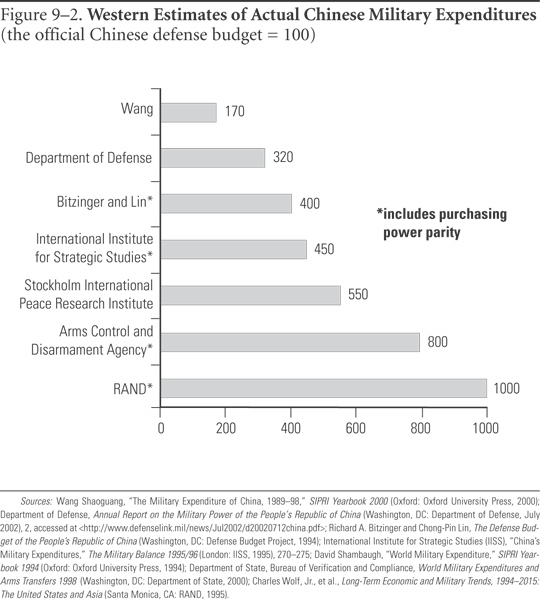

Research and development (R&D) costs. It is generally believed that military R&D is funded from other parts of China's state budget. Wang Shaoguang, in fact, argues that the Chinese freely acknowledge this fact and that defense R&D is specifically covered under the country's general R&D fund and from a special fund for "new product promotion.'6 Second, we are reasonably certain that some kind of purchasing power parity (PPP) formula should be applied to Chinese defense expenditures to provide a more accurate reflection of their true value in terms of relative spending power. Many goods in the Chinese defense spending basket cost much less than they would in the West: conscription and lower living standards in the PLA save money on personnel, while lower wages at defense factories depress the cost of arms procurement. These disparities should be corrected by some kind of PPP multiplier, especially when attempting to compare Chinese defense spending to military expenditures in other countries. Unfortunately, after these few facts and reasonable assumptions, reliable data regarding Chinese defense expenditures get much shakier. In fact, the unknowns and the unknowables concerning Chinese military expenditures greatly outnumber our known data. For example, beyond the highly aggregated spending figures for personnel, O&M, and equipment, we lack any further details as to how China's official defense budget is distributed. Specifically, we do not know how much funding goes to the army, air force, or navy; how much is spent on which particular R&D and procurement programs; the amounts and types of weapons (aircraft, ships, tanks, or missiles) being procured annually; or how much support is specifically accorded to categories such as training or logistics, or toward improving soldiers' living standards. In addition, we lack such detailed budgetary figures over time, which would permit trend and tradeoff analyses. Compounding this lack of detail concerning the declared defense budget, we do not know the actual amount of China's extrabudgetary military expenditures. For example, while we are reasonably certain that defense R&D costs are not reflected in the official budget, we have no idea how much the Chinese really spend on R&D or on what particular programs and how much funding is allocated to each project (both annually and over time). Nor can we ever be certain how much the PLA nets from its commercial business activities or the percentage of these profits that actually ends up benefiting the military rather than being siphoned off into private overseas bank accounts or spent on new automobiles for senior officers. Finally, while we are reasonably sure that some kind of PPP exists for Chinese defense spending, we have no clear idea what it actually is; PPPs for China vary widely. In addition, many PPPs do not account for the inferior quality of Chinese products (such as weapon systems) or services (such as the effectiveness of individual soldiers) relative to the West; therefore, they may actually overvalue Chinese expenditures. As one Western defense analyst has stated, "Unfortunately, purchasing-power parity measures are very difficult to compute and inherently imprecise. Among the chief challenges are uncertainty over which goods to place in the 'defense spending basket' and which goods to consider strictly comparable between one country and another."13 Given the absence of data regarding Chinese military expenditures, Western analysts have been forced to fall back upon extrapolation, inference, and conjecture to come up with reasonable guesses as how large extrabudgetary spending is, how it should be valued (that is, how large a PPP should be applied to the data), and how much is likely spent on defense R&D and procurement. This approach is fraught with many methodological pitfalls. For example, in attempting to calculate a reasonable procurement budget, analysts typically factor two "guesstimates" (how much a particular item might cost and how many might be purchased); basic probability theory should caution us that the resulting budget figure would be a highly unreliable number. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that these efforts have resulted in a broad range of estimates of likely Chinese defense spending (figure 9-2) that--depending on one's assumptions regarding extrabudgetary inputs, their valuations, and PPPs--differ from each other by more than a factor of 10. Even if one excludes the most extreme estimates, Western calculations of Chinese military expenditures still vary by around 300 percent. This bigger-than-a-breadbox/smaller-than-an-elephant type of analysis does little to help us understand the practical implications of actual Chinese defense spending. Nor do we possess sufficient detail about Chinese military expenditures to make assertions about specific military priorities, intentions, plans, or procurement. In particular, we have no data as to how defense spending is directly affecting power projection capabilities, training, morale, living conditions, R&D, and high-tech weaponry. Consequently, defense budget analysis provides little help when it comes to assessing Chinese defense modernization efforts and likely future military capabilities. We may argue that higher or increasing defense spending is "threatening," but we cannot identify specifically where and to what extent.

Speculation about Chinese Procurement SpendingIn the absence of additional budgetary data, analysts can do little more to advance the field of Chinese defense budget analysis. We might press the Chinese to be more forthcoming and transparent about military expenditures--to release more detailed defense budgets, along with additional (and more detailed) defense white papers--but we should not be too optimistic that this will garner significant results in terms of data. While Chinese-language sources probably exist that could provide additional insights into the defense budget, these are also unlikely to include the kind of detailed, over-time data conducive to more in-depth budgetary analysis.14 Therefore, more than searching for additional sources of data, we should attempt to use what is known about Chinese military expenditures to engage in innovative or alternative approaches to analysis and assessment. For example, we might attempt to assess how far likely spending levels could go in covering basic defense requirements for near-term procurement (2002-2006). Such an approach is based on several assumptions:

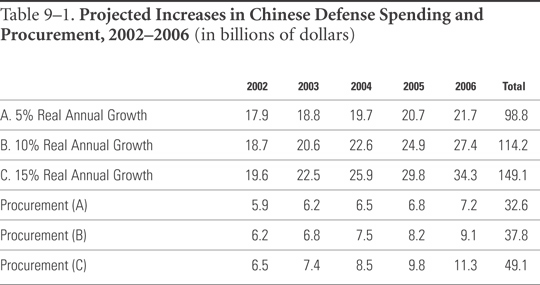

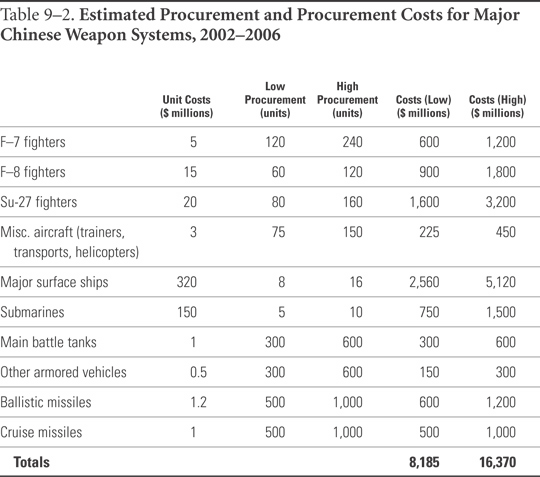

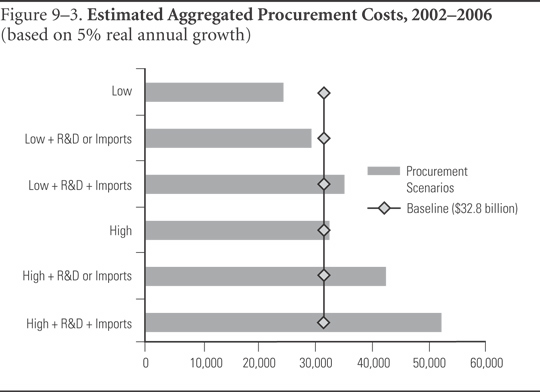

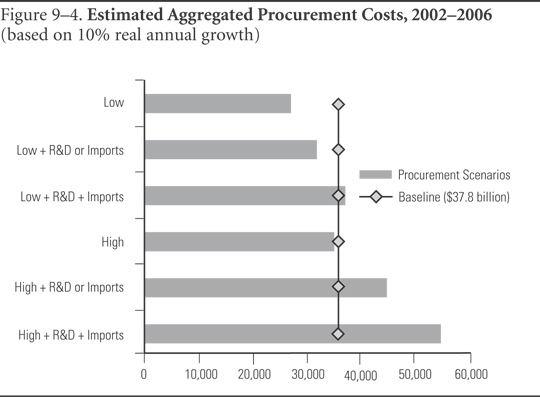

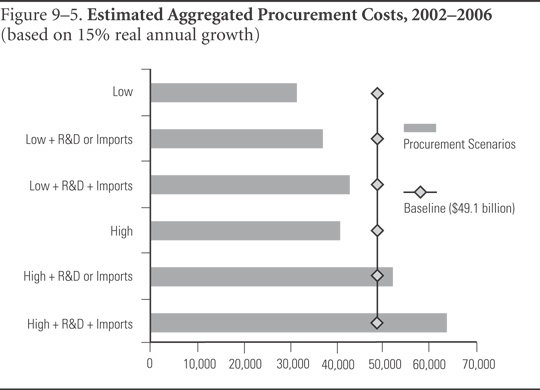

Armed with these assumptions, we simply total up likely procurement costs for this period (controlling for possible extrabudgetary items, such as defense R&D and arms imports) and compare this to likely procurement budgets (figures 9-3, 9-4, and 9-5). What we find is that, in most cases, projected expenditures fall below projected budgets. Therefore, it would appear that, at a 10 percent or even 5 percent annual growth rate, the Chinese could conceivably afford a modest arms buildup (including R&D and arms imports) over the next 5 years, based solely on official budgetary numbers. Naturally, if defense R&D and arms imports are truly extrabudgetary, or if defense spending grows at a higher rate, then the buildup could be even more substantial. If the Chinese are able to maintain 10 percent real annual average growth in defense spending out to 2010, then by the end of the decade the PLA could conceivably possess:

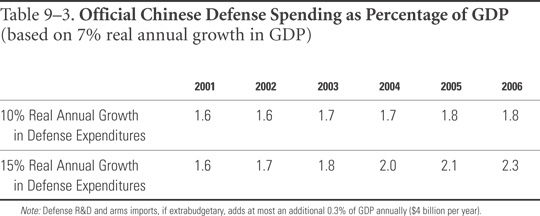

At the same time, China's defense burden is likely to remain manageable, provided the economy continues to grow. At 7 percent annual GDP growth, even a 15 percent annual increase in the defense budget would absorb less than 3 percent of China's GDP by the middle of the decade (see table 9-3). Of course, all this speculation is fraught with caveats. Growth rates of 10 to 15 percent may ultimately be unrealistic or unsustainable, from either an economic or political standpoint. In addition, procurement costs could be much higher than estimated. Consequently, the PLA could be facing a considerable "procurement bow-wave" by the middle of the decade, as several new and expensive weapons programs come online after 2006 or so. Finally, personnel and O&M costs could rise significantly over the next several years, as Beijing attempts to compensate the PLA for business divestitures, as China attempts to meet growing quality-of-life needs for its soldiers, and as the PLA expands training, readiness, and logistics to meet the demands of a more high-tech force. Overall, therefore, while the PLA may be the beneficiary of an increasing defense budget, it may also be saddled with growing requirements that will strain its available financial resources.

Suggestions for Attempting Future AnalysisIn thinking about ways to address the issue of Chinese defense budgets and military expenditures further, we can attempt to improve our methodologies and make our work more intellectually rigorous and honest. Specifically: We should discount unsophisticated analytic approaches that simply fix military expenditures at a "reasonable" percentage of GDP. We should also discount analysis based on old, highly massaged data. (I specifically refer here to the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency [ACDA] approach to calculating Chinese military expenditures, which is based on a PPP conversion rate that is nearly 20 years old. In fact, ACDA admits that its estimations of Chinese military spending "should be treated as having a wide margin of error."15) We should avoid politicizing Chinese budgetary analysis. This includes both "kitchen-sinking" and "low-balling" extrabudgetary expenditures to produce a desired budgetary figure that either supports or undermines a "China threat" argument. At the same time, we should be careful not to get caught up in groupthink and purposely skew our data to fit the middle of the bell curve. We should discount approaches that do not include some kind of PPP formula. Just because we do not know precisely what the PPP formula is for Chinese defense budgets does not mean that one does not exist. We should endeavor to come up with better and more reliable methodologies for calculating PPPs for Chinese military expenditures. We should not let worst-case thinking dominate budget assessments. In particular, we need to address and argue specifically why extrabudgetary or increasing military expenditures should be considered threatening and not just take it as a self-evident fact. Likewise, we should be careful when stating that "Chinese defense expenditures could be as high as . . . " since one person's high-end estimates often become another's baseline arguments. We should attempt to be more interdisciplinary and engage more outside functional experts--particularly genuine number-crunching budgetary analysts--in our research. We should also query Western Sovietologists as to how they came up with estimates of Russian defense spending during the Cold War. At the very least, these sources of expertise can validate our methodologies. Above all, we should resist the easy temptation to make the bottom line the crux of our analysis"to give out a single figure of X billion yuan or dollars as the likely Chinese defense budget and simply leave it at that. In this regard, we are only perpetuating the same dilemma that we encounter with the official top-line figure for Chinese defense spending: we fail to provide any reliable indicators of where the money is going and why. In the absence of any further data--that is, what the Chinese are specifically spending their defense budget on and whether it is cost-effective, what their spending trade-offs are, how this spending compares to other countries' military expenditures--such an effort offers little useful information or analysis. Finally, we need to be honest with ourselves: Given the current (and probably ongoing) paucity of data, we should acknowledge the severe limitations of any effort to analyze and assess Chinese military expenditures. Moreover, the consumer of our research deserves to know the considerable uncertainty and high probability of error present in our methodologies and outcomes. Until we have more data, defense budget analysis of Chinese military affairs will function best as an adjunct to or a check on other types of empirical research--areas where the arguments are likely to be more impressionistic and less quantitative.

Notes1Recent Western literature on Chinese defense expenditures includes David Shambaugh, "Wealth in Search of Power: The Chinese Military Budget and Revenue Base," paper delivered to the Conference on Chinese Economic Reform and Defense Policy, Hong Kong, July 1994; Bates Gill, "Chinese Defense Procurement Spending: Determining Intentions and Capabilities," in China's Military Faces the Future, ed. James R. Lilley and David Shambaugh (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1999); Arthur Ding, "China Defense Finance: Content, Process, and Administration," China Quarterly, June 1996; Wang Shaoguang, "Estimating China's Defense Expenditure: Some Evidence from Chinese Sources," China Quarterly, September 1996; Wang Shaoguang, "The Military Expenditure of China, 1989-98," SIPRI Yearbook 2000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000); International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), "China"s Military Expenditures," The Military Balance 1995/96 (London: IISS, 1995), 270-275; and Richard A. Bitzinger and Chong-Pin Lin, The Defense Budget of the People's Republic of China (Washington, DC: Defense Budget Project, 1994). [BACK] 2Robert Karniol, "PRC Spending Continues to Rise," Jane's Defense Weekly, March 14, 2001 (Internet version). [BACK] 3Lester J. Gesteland, "China Defense Budget Up 15-19% This Year," ChinaOnLine News, January 31, 2000, accessed at <http://www.chinaonline.com>. [BACK] 4Craig S. Smith, "China Sends Its Army Money, and a Signal to the U.S.," The New York Times, March 11, 2001 (Internet version). [BACK] 5Si Liang, "Increase in China's Military Is Still at a Low Level," Zhongguo Tongxun She (Hong Kong), March 8, 2001, translated and reprinted by Foreign Broadcast Information Service (Internet version); Sun Shangwu, "China Daily Interviews PLA Logistics Deputy Director on Military Budget Increase," China Daily, March 12, 2001 (Internet version). [BACK] 6Wang, "The Military Expenditure of China, 1989-98," 339. [BACK] 7U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Verification and Compliance, World Military Expenditures and Arms Transfers 1998 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State, 2000), 129. [BACK] 8Wang, "The Military Expenditure of China, 1989-98," 338; David Shambaugh, "World Military Expenditure," SIPRI Yearbook 1994 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 447. [BACK] 9John Frankenstein, "China's Defense Industries: A New Course?" in The People's Liberation Army in the Information Age, ed. James C. Mulvenon and Richard H. Yang (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1999),197-199; John Frankenstein and Bates Gill, "Current and Future Challenges Facing Chinese Defense Industries," China Quarterly, June 1996, 419-420; "Three Kings: Over Half of China's Industrial Profits in Jan.-Apr. Ruled by 3 Sectors," ChinaOnline News, June 28, 2000, accessed at <www.chinaonline.com>. [BACK] 10Harlan Jencks, "COSTIND is Dead, Long Live COSTIND! Restructuring China's Defense Scientific, Technical, and Industrial Sector," in The People's Liberation Army in the Information Age, ed. James C. Mulvenon and Richard H. Yang (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1999), 61; "The Crisis of State-Owned Enterprises in Mainland China Worsens," Cheng Ming (Hong Kong), November 1, 1996, 54-57. [BACK] 11Wang, "The Military Expenditure of China, 1989-98," 344-347; Shambaugh, "Wealth in Search of Power," 15-20; IISS, "China's Military Expenditures," 273. [BACK] 12For more on PLA commercial business activities and subsequent divestiture, see James C. Mulvenon, Soldiers of Fortune (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000). [BACK] 13Michael E. O'Hanlon, "The U.S. Defense Spending Context," in The Changing Dynamics of U.S. Defense Spending, ed. Leon Sigal (Westport, CT: Praeger Press, 1999), 14. [BACK] 14David Shambaugh and Bates Gill have identified a few Chinese sources on the defense budgeting process, but these appear to be overviews of the budgeting process and budget management, rather than detailed accountings of military expenditures. See Zhongguo junshi jingfei guanli (Chinese Military Expenditure Management), ed. Lu Zhuhao (Beijing: Jiefangjun Chubanshe, 1995); Zhongguo junshi caiwu shiyong daquan (Complete Practical Guide to Chinese Military Finance) (Beijing: Jiefangjun chubanshe, 1993); Liu Yichang and Wu Xizhi, Guofang jingjixue jichu (Basics of Defense Economics) (Beijing: Junshi Kexue Chubanshe, 1991). [BACK] 15See World Military Expenditures and Arms Transfers 1998, 203-204. [BACK] |

| Table of Contents I Chapter Ten

|

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|