|

SAND2000-0184 Unlimited Release Printed January 2000

Conceptual Monitoring Options for a Southern Lebanon Withdrawal Agreement

Charles W. Spain International Assessments Program Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Livermore, CA

94551 Lawrence C. Trost Arms Control Studies Department Michael G. Vannoni Advanced Concepts Department Sandia National Laboratories P.O. Box 5800 Albuquerque, NM

87185-1371 Abstract Southern Lebanon is a key factor in a comprehensive Middle East peace settlement. Israel has had a presence in southern Lebanon since 1976 and occupied a self-described "security zone" there in 1985. The purpose of this study is to outline options for

cooperation in southern Lebanon that address the security goals of the players

and may help facilitate a withdrawal agreement. Three scenarios were developed

to address the security goals of the participants, each requiring increasing

levels of cooperation. These

scenarios and options for cooperative monitoring are described in this report.

Acronyms GPS Global Positioning System IDF Israeli Defense Forces ILMG Israel-Lebanon Monitoring Group IRGC Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps JMG Joint Monitoring Group LAF Lebanese Armed Forces MoD Ministry of Defense OP Observation Post PLO Palestine Liberation Organization SLA South Lebanon Army UAV Unmanned Aerial Vehicle UGS Unattended Ground Sensors UNIFIL United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon UNSCR United Nations Security Council Resolution

Contents Executive Summary................................................................................................................................................................

7

Introduction............................................................................................................................................................................

9

Background............................................................................................................................................................................

10

The Historical Context of the Israeli Presence

in Southern Lebanon.......................................................

10

Key Players and Their Goals.......................................................................................................................................

15

Israel: Secure Its Border...................................................................................................................................................

15

The South Lebanon Army:

Just Fade Away..............................................................................................................

16

Lebanon: Regain Its Sovereignty...................................................................................................................................

16

Syria: Protect Its Flank....................................................................................................................................................

16

Iran: Strengthen the Shia................................................................................................................................................

18

Hizballah: Liberate Lebanon..........................................................................................................................................

19

Current Monitoring Efforts......................................................................................................................................

21

United Nations......................................................................................................................................................................

21

Multilateral........................................................................................................................................................................

23

Recent Israeli Proposals for Withdrawal.....................................................................................................

24

If Withdrawal Comes....................................................................................................................................................

25

Cooperative Monitoring Options............................................................................................................................

26

Introduction..........................................................................................................................................................................

26

Possible Monitoring Options...........................................................................................................................................

26

A Low Cooperation Regime..............................................................................................................................................

27

Features of the Low Cooperation Regime.......................................................................................................................

28

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Low

Cooperation Regime..............................................................................

30

A Medium Cooperation Regime.......................................................................................................................................

30

Features of the Medium Cooperation Regime................................................................................................................

30

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Medium

Cooperation Regime.......................................................................

31

A High Cooperation Regime..............................................................................................................................................

31

Features of the High Cooperation Regime......................................................................................................................

31

Advantages and Disadvantages of the High

Cooperation Regime............................................................................

32

Comparison of the Three Regimes..................................................................................................................................

33

National Means....................................................................................................................................................................

33

The Role of UN Peacekeepers..........................................................................................................................................

33

Summary and Conclusions...........................................................................................................................................

34

Appendix A: Relevant United Nations

Resolutions......................................................................................

35

Appendix B: Text of April 26, 1996 Cease-fire

Understanding..................................................................

37

Figures

Figure 1. Map of

Lebanon..................................................................................................................................................

11

Figure 2.

Israeli Security Zone in Southern Lebanon.....................................................................................

13

Figure 3.

IDF Casualties in Lebanon, 1990-1998........................................................................................................

15

Figure 4.

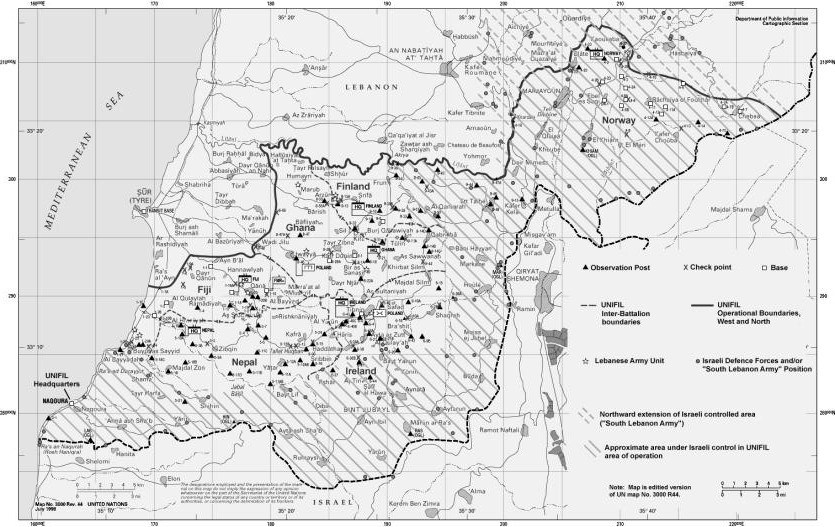

UNIFIL, IDF/SLA, and LAF Positions and Zones of Control.........................................................

22

Figure 5.

Representative Unattended Ground Sensors (UGS).....................................................................

28

Figure 6.

Pioneer UAV............................................................................................................................................................

32

Tables Table 1. Functional

Components of the Three Cooperative Monitoring Regimes.......................

33

Southern Lebanon is a key factor in any comprehensive Middle East peace settlement. Israel has maintained a political and military presence in southern Lebanon since 1976 and occupied a self-described "security zone" since 1985. The United Nations Security Council issued Resolution (UNSCR) 425 in March 1978 calling for the withdrawal of all Israeli forces from Lebanon and for United Nations peacekeepers to restore peace and security there. Israel largely ignored UNSCR 425 until April 1998 when the Israeli inner cabinet unanimously acknowledged the resolution. Israeli officials described two options for action: 1) a withdrawal based on bilateral negotiations with Lebanon, and 2) a unilateral withdrawal with the implied right to reenter Lebanon if deteriorating security conditions require it. At the time of writing (spring 1999), it is not clear how the Israelis will proceed. The ultimate resolution of these issues requires major decisions about national security by Israel, Lebanon, and Syria. Each of the key players involved in southern Lebanon has specific goals that will affect their security decisions: Israel seeks a secure northern border. Members of Israel's allied South Lebanon Army seek a way to withdraw without retribution. Lebanon seeks to regain sovereignty in the southern part of the country. Syria wants to protect its western flank and maintain political influence in Lebanon. Iran wants to strengthen its influence with Lebanon's Shia population. Hizballah seeks to force the Israeli army out of Lebanon. The purpose of this study is to outline options for cooperation in southern Lebanon that address the security goals of the players and may help facilitate an agreement. The study is not prescriptive and assumes that a political arrangement for Israeli withdrawal has been reached. Cooperation may take a number of forms. Israel has an interest in a stable Lebanese government in control of southern Lebanon. In some circumstances, Israeli security could benefit from Lebanese armed forces with capabilities enhanced through equipment upgrades and technical training. Direct Israeli support for these enhancements could provide the basis for cooperative monitoring of southern Lebanon by Israel and Lebanon. Cooperative monitoring is the collection (often by the use of sensors), analyzing, and sharing of information among parties to an agreement. Three cooperative monitoring scenarios were developed to address the security goals of the participants, each requiring increasing levels of cooperation. Some options for cooperative monitoring identified in the three scenarios are LOW COOPERATION · Joint military patrols along border. · Enhanced border-crossing points between Israel and Lebanon. · Means of notification of military activities and border incidents. · Enhanced monitoring ability for Lebanese military. MEDIUM COOPERATION (in addition to or in place of those in LOW) · Border monitoring sensors that report to Israeli and Lebanese military commands. · Procedures for coordinated operations. · Enhanced Lebanese interior checkpoints. · Introduction of a multinational supervisory organization. · A shared border communications network. HIGH COOPERATION (in addition or in place of those in MEDIUM) · A multinational monitoring organization with operational responsibilities. · A monitoring and coordination center, staffed by parties to an agreement. · A real-time reporting network for the monitoring center · Enhanced border monitoring sensors including unmanned aerial vehicles On April 1,

1998, the Israeli inner cabinet*

unanimously accepted United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 425,

which calls for the withdrawal of Israeli forces from Lebanon.

The cabinet's acceptance came 20 years after the Security Council

adopted UNSCR 425 and renewed domestic and international debate over the Israeli

government's Lebanon policy. The future status of the Israeli military presence in Lebanon

was an issue in Israel's May 1999 election.

Prime Minister Ehud Barak has indicated he would like to withdraw Israeli

troops from southern Lebanon although he has not yet described a plan to do so.

At the time of writing (spring 1999), Israel Defense Forces (IDF) remain

engaged in a guerrilla war with various armed factions in southern Lebanon. Any eventual Israeli decision for withdrawal is inextricably

linked to larger regional issues, particularly relations with Syria and the

dormant Middle East Peace Process. In light of

the Israeli acceptance of UNSCR 425, an examination of the potential roles

cooperative monitoring could play in building confidence or implementing an

agreement among the parties in southern Lebanon is timely.

Cooperative monitoring is the collecting (usually through the use of

sensor technology), analyzing, and complete sharing of information among parties

to an agreement. The issues that

surround the Lebanon imbroglio are complex, and an effective cooperative

monitoring regime must account for the myriad interests there.

This paper will describe the history of the conflict, the players and

issues present on the contemporary Lebanon-Israel border and then discuss

potential cooperative monitoring activities within this context.

These measures might help support a future withdrawal agreement and

improve confidence that the respective security interests were being addressed. Israel's

security dilemma in southern Lebanon began shortly after the Six-Day War of June

1967. In 1968, guerrillas of the

Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) began to use southern Lebanon as a base

for occasional attacks on Israeli border towns and military facilities (see

Figure 1 for a map of Lebanon). In

September 1970, the government of the Kingdom of Jordan, alarmed at the PLO's

rising influence and power in its country, began a military campaign to expel

the PLO from Jordan. In 1971, the

PLO headquarters and its paramilitary organization relocated to Lebanon.

From their new bases in southern Lebanon, the PLO escalated its military

campaign of attacks, cross-border shelling, and infiltration against Israel.

The government of Lebanon steadily lost functional control of the area

the PLO occupied in the South. In

1975, the civil war began in Lebanon and, over time, reduced the government's

effective control to a small area around Beirut.

The Lebanese military splintered along religious lines and ceased to have

any power in the South. By the late

1970s, Israel-Lebanon border was a battleground with recurrent conflict between

the Israeli army and the PLO. The Historical Context of the Israeli Presence in Southern LebanonIn

the summer of 1976, the Israeli presence in southern Lebanon began with Defense

Minister Shimon Peres' announcement of the "Good Fence" program.

This allowed local Lebanese to cross into Israel for work, medical

treatment, and travel. In addition, the policy gave Israel access to both Lebanese

collaborators and southern Lebanon in its battle with the Palestinian forces

there. Israel allied itself with

Major Sa'ad Haddad, a Greek Catholic Lebanese army officer who had been sent

south by Beirut in 1976 to help organize the defense against Palestinian and

leftist forces. Haddad later

ignored orders and remained in the South after the collapse of the Lebanese

army. He formed his own militia

army, the South Lebanon Army (SLA), and became Israel's proxy in its campaign

against the PLO.[i] During the

next six years Israel and the SLA battled the Palestinian forces in southern

Lebanon. Israel launched two major

military offensives. Operation

Litani, begun in March 1978, displaced the PLO along the border, created

200,000 civilian refugees, and caused the United Nations Security Council to

approve Resolution 425 (UNSCR 425) calling for the withdrawal of Israeli and

immediate deployment of a UN peacekeeping force (see Appendix A).

Israel withdrew its forces by June 1978 but turned its positions over to

the SLA, not the United Nation Interim Forces in Lebanon (UNIFIL).[ii]

Infiltration and cross-border attacks by rockets, although reduced in

frequency, continued. In June 1982, Israel launched Operation

Peace for Galilee to rid Lebanon of the PLO. By late 1982, the PLO headquarters and its remaining military

forces evacuated Lebanon and relocated to Tunisia. Israeli forces pulled back from their positions in central

Lebanon and around Beirut but remained in southern Lebanon along with the SLA.

This

extended occupation initiated Israel's current conflict with the Shia Moslem

Lebanese who have historically lived in southern Lebanon.

Lebanon's

southern Shia population is the poorest and largest community in the country[iii]

and has been historically underrepresented in the government.

Many Shia have been attracted to groups promising a change in the status

quo.[iv]

The movement of the PLO to southern

Lebanon in 1971 largely displaced the central government.

Over time, the Shia felt they were under foreign occupation.

Consequently, when Israel invaded in 1982, the Shia initially welcomed

the Israelis. In 1983 Shia

attitudes towards Israel began to change when they realized that the Israelis

were not going to withdraw. The

Shia concluded that they had exchanged one foreign occupation for another.

The IDF viewed the shift in Shia support as challenging their authority.

Several violent confrontations occurred between the IDF and the Shia. In

November 1983, a guerilla war began between the Shia militias and the IDF.

The goal of the militias was, and still is, to force a complete Israeli

withdrawal from Lebanon. By 1984, the Shia were launching frequent attacks against the

IDF. In response, Israel withdrew

the bulk of its forces in Lebanon between January and June 1985 but created a

"security zone" averaging 10 km wide along the Israel-Lebanon border

patrolled by an IDF garrison along with the SLA.[v]

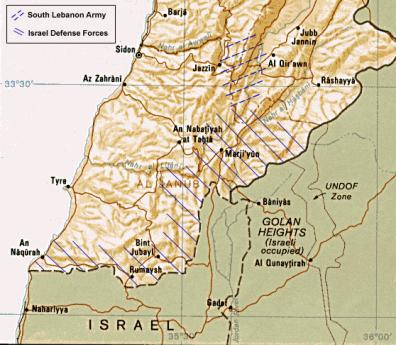

The areas controlled by the IDF and SLA are shown in Figure 2.

Shia militias continued their fight against the SLA and IDF in Lebanon

throughout the rest of the 1980s and early 1990s and used the area to launch

attacks on Israel's northern settlements and as an infiltration route to

conduct terrorist operations inside Israel.

Figure 2. Israeli Security Zone in Southern Lebanon By

the early 1990s the Hizballah militia had become the primary Shia guerrilla

force fighting to oust the Israelis. IDF

casualties sharply increased in 1992 as Hizballah improved both its weapons and

military organization. The Shia

militias received money, training, and arms from Syria (to pressure Israel) and

Iran (to support Islamic revolution). In

response, Tel Aviv launched its third major offensive in southern Lebanon, Operation

Accountability, on 25 July 1993. The

goal was to cripple the military capability of Hizballah and apply pressure on

Syria to disarm Hizballah. By

the end of July 1993 American mediation efforts had stopped the fighting and led

to an unwritten "understanding" under which Hizballah forces would

stop launching rockets into Israel. U.S.

Secretary of State Warren Christopher brokered the understanding with

".Israel, Syria and Lebanon and through indirect contacts with

Iran."[vi]

Israeli officials declared victory saying their offensive resulted in the

Hizballah pledge not to fire on northern Israel.

Hizballah publicly vowed to continue its fight against the Israeli

occupation of Lebanon, which the "understandings" did not prohibit,

but said it would stop its rocket attacks".as long as Israeli forces

[did] not fire on Lebanese civilians."[vii] Although

conflict in the security zone continued, shelling of northern Israel ceased.

The unwritten understandings of 1993 collapsed on April 11, 1996 with the

beginning of Israel's fourth military offensive into Lebanon, Operation

Grapes of Wrath. The offensive

was in retaliation for a surge of Hizballah attacks against Israeli troops and

northern Israel. Tel Aviv targeted Lebanese infrastructure in Beirut, such as

electrical supply stations, to put a new form of pressure on the Lebanese and

Syrian governments to restrain Hizballah. On

April 18, Israeli artillery shells landed inside the UN military compound in

Qana killing approximately 100 civilian refugees and injuring another 100.

Allegations were made that the shelling was deliberate. Whatever

the cause of the Qana tragedy, Israeli public support for the operation

evaporated and the Clinton Administration began to apply significant pressure on

Israel to implement a cease-fire. Secretary

Christopher negotiated an end to the fighting and the so-called "April 26,

1996 Understanding," between Israel and the government of Lebanon.

The agreement protects civilians by prohibiting attacks on civilian

targets or from civilian areas (see Appendix B).

The April 26 Understanding added a new feature in an attempt to stabilize

conditions in southern Lebanon: the

Israel-Lebanon Monitoring Group (ILMG).

The ILMG is an independent monitoring group composed of representatives

from Israel, Lebanon, Syria, France, and the United States with the goal of

assessing the application of the April 26 Understanding. Conditions

in southern Lebanon are largely unchanged at the time of writing.

Shia

militias attack IDF/SLA positions and attempt to infiltrate into Israel. The

political and military context for the conflict in southern Lebanon is among the

most complex in the Middle East. As

the previous discussion illustrates, activities there impact the interests of

state and non-state actors, primarily Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Iran, and

Hizballah. Each sees southern

Lebanon's future in terms of its respective goals.

Understanding the players and their goals is central to application of

cooperative monitoring. Israel: Secure Its BorderSince the

late 1970s, Israel's stated goal has been to secure its northern border

against military, guerrilla, and terrorist attack.

Israel's efforts originally were focused on the threat posed by the

PLO. After being forced out of

Jordan, the PLO established bases throughout Lebanon and used the South to

launch repeated attacks against Israel's northern towns. The government of Israel established the self-declared

"security zone" to provide an armed buffer zone between PLO forces and

Israel. Israel's

costly success in driving the PLO from Lebanon and establishing its buffer zone

ironically produced a new threat: the

Shia resistance. Just as the PLO

before them, but with less local resentment, the militias used the South to

launch attacks against Israeli forces, northern towns, and as an infiltration

route to conduct terrorist operations inside Israel. Israel's

response to the Shia militias was similar to that against the PLO.

IDF forces used the "security zone" as a buffer between the armed

groups and Israel and as a base for operations against them.

Today, Israel maintains about 1,500 soldiers in Lebanon.

Guerrilla groups attack almost daily and inflict casualties on the IDF

(see Figure 3).

(Casualty

data from Israel Defense Forces, Spokesperson's Office, Information Branch

from the Internet) Figure 3. IDF Casualties in Lebanon, 1990-1998 The South Lebanon Army: Just Fade AwayThe SLA has

fought beside the IDF from the very beginning as Israel's Lebanese proxy.

The group has been funded by Israel and does not have clearly defined

political goals. It is difficult to

imagine the group's continued existence after an IDF pullback.

The rank and file of the 2,200-man SLA (about 55 percent Muslim and 45

percent Christian) probably would not have much difficulty returning to their

villages and civilian life. The

senior leadership, however, could face severe reprisals.

The Lebanese government in late 1996 sentenced current SLA Commander

Antoine Lahd to death in absentia for

his collaboration with Israel. SLA

senior leadership likely would flee to Israel or other countries outside the

region to escape Lebanese retribution. Some

of these officers, including Lahd, reportedly have already acquired foreign

passports.[viii] Lebanon: Regain Its SovereigntySince

the end of the civil war in 1990, the internationally recognized government in

Beirut has remained a peripheral player in the conflict due to its subordinate

relationship with Syria. Syria

strongly influences Lebanon's foreign policy decisions, given the power of

30,000 Syrian troops in Lebanon remained after the civil war. The 60,000-man Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) collapsed during

the civil war and has lately focused on rebuilding itself.

The LAF is not deployed throughout the country.

The government in Beirut has said that once the Israelis withdraw, the

LAF will deploy south. Lebanon has

largely placed its goal of regaining its sovereignty in the South in the hands

of the international community. Syria: Protect Its FlankSyria is a

key participant in southern Lebanon. Beginning

in 1970, Syria's primary interest in Lebanon became one of protecting its

western flank, politically as well as a militarily.

When the PLO took up residence in Lebanon, Syrian President Asad became

"... intensely interested in every twist of Palestinian politics."[ix]

Israel's close relations with Lebanon's Christian community and its

nascent war with the leftists and PLO there left Asad with the threat of either

a significant gain in Israeli influence, or a war on his border that could

eventually involve Syria. When civil

war erupted in 1975 among Lebanon's Palestinian, Muslim and Christian camps,

security became Asad's primary concern. If

Syria remained on the sidelines, the Christians might win and set up a separate

Christian state with Israel as protector. If

the Christians lost, Israel might intervene to protect its interests.

Asad attempted to negotiate with the warring factions to stave off a

Lebanese collapse but with the disintegration of the LAF into its religious

factions in March 1976; Asad saw no alternative to intervention.

During the night of May 31, 1976, Syrian regular army units crossed into

Lebanon"...to teach the Palestinians sense and to keep the Christians Arab."[x]

Syria' s intervention in Lebanon was no surprise to Israel.

As a result of American negotiation, Israel had agreed to a limited

incursion in an unwritten "red-line" agreement, which limited the number of

Syrian troops south of the Damascus-Beirut road and restricted air and naval

deployments. By late 1976,

Syria's military intervention had ended the fighting.

In October, Asad attended a Saudi Arabian-sponsored peace summit, which

legitimized Syria's presence in Lebanon.

Syrian forces in Lebanon became part of an "Arab Deterrent Force"

funded by Kuwait and Saudi Arabia and supported by troops from other Arab

militaries. Syrian forces gained

control over all of Beirut by November, the militias fled, and the civil war was

declared over.[xi]

Despite his success in ending the fighting, Asad's efforts to

keep the Israelis out of Lebanon failed. In

1983 Israel and Lebanon signed a joint security agreement that provided for an

Israeli withdrawal if the Syrians withdrew.

Syria rejected this offer. Fighting

among the various religious groups within Lebanon resumed in the mid-1980s again

drawing Syrian forces into the conflict. By

1988 the deep rifts between these groups resulted in a presidential secession

crisis in Lebanon. A leadership

vacuum and renewed fighting followed. With

the Lebanese economy in shambles and a breakdown in public services looming, 62

members of the Lebanese parliament -- evenly split between Christian and Muslim

--met in Ta'if, Saudi Arabia in late 1989.

The meeting produced the "Document of National Understanding," more

commonly referred to as the Ta'if Accord.

The accord implicitly recognized the necessity of compromise while not

abandoning the ultimate goal of political unification under a "national"

government, superior to the religious groups.

The Ta'if Accord, accepted by the Lebanese legislature in 1990,

effectively ended the civil war. It

also formalized Lebanon's "special relationship" with Syria and only

required Asad to redeploy his forces to the Bekaa Valley within two years.[xii]

Today, Syrian forces not only remain in the Bekaa Valley, but also in

Beirut and northern Lebanon.[xiii] Syria's

presence in Lebanon has become inextricably linked to Asad's agenda in the

stalled Middle East Peace Process (MEPP). Syria's

30,000 troops in Lebanon are the ultimate guarantor of Asad's interests there

and were critical to the successful disarming of the various militias at the end

of the civil war. Asad allowed

Hizballah to retain its weapons, however, to support the guerrilla action

against the Israelis in the South. Syria

defined Hizballah operations as legitimate resistance to Israeli occupation.

Syrian support to Hizballah also includes serving as a resupply conduit

for Iranian assistance.[xiv] Syrian

support to the Hizballah guerrillas figures prominently in Asad's strategic

posturing with Israel. President

Asad's primary goal in any peace deal with Israel is a return to the June 4,

1967 border that returns the Golan Heights to Syrian control.

Asad apparently concluded that he could not retake this strategic plateau

lost to Israel in 1967 by force. Instead

he looked to the diplomatic arena for a solution.

However, with the collapse of MEPP negotiations with Israel in 1996, Asad

turned again to his "Hizballah card" to keep pressure on Israel and remind

it of the costs of not having a comprehensive peace agreement.

When Israel floated proposals in 1996 for resolving the security issues

with Lebanon bilaterally, Syria and Lebanon publicly restated the linkage

between the return of the Golan, quiet along the Lebanon border and

comprehensive peace with Israel. Asad

told reporters, "Syria and Lebanon first - at the same time, in the same

steps."[xv]

Asad's manipulation of Hizballah guerrilla activities in southern

Lebanon provides the only real leverage Syria enjoys over Israel. Iran: Strengthen the ShiaIran's

interests in Lebanon have been closely linked to the plight of the Shia Muslims

there. A charismatic Iranian cleric

of Lebanese ancestry provided a political outlet for Shia fervor. Musa al-Sadr began a populist reform movement after his

return to Lebanon in 1959 and by 1975 had organized his own armed militia, Amal

(an acronym of Afwaq al Nuqawamah al Lubnanya, the "Units of the Lebanese

Resistance"). Musa al-Sadr said

Amal was distinct from other militias in Lebanon in that its men were

"...trained to go to the South and fight Israel."[xvi]

Tehran's efforts have been channeled through various Shia groups

(indirectly through Amal at first and directly through Hizballah more recently)

and intended to improve conditions for the Shia and to spread the Islamic

"revolution" started by Ayatollah Khomeini.[xvii] By the time

of Israel's invasion of 1982, however, Amal had split into two factions.

One was secular in nature, rejected an "Islamic Republic of Lebanon,"

and sought political accommodation with Israel.

This group also was more beholden to Syria for support.

The other faction "...viewed Amal as the vanguard of revolutionary

struggle ... based on the model and ideals of the Iranian revolution"[xviii]

and won Iran's favor. In June

1982 several senior members of Amal allied to the Iranian faction split and

started the Islamic Amal based in

Lebanon's Bekaa Valley Iranian

support for the ideals of Islamic Amal was strengthened with the arrival in

mid-1982 of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Tehran sent a small contingent of IRGC to Lebanon ostensibly to fight

Israeli forces in the South but this role was "...blocked by Syria as well as

Khomeini himself for strategic reasons."[xix]

The IRGC did play a critical role in the immediate survival of Islamic Amal,

however, and in its eventual merging with other radical Lebanese Shia movements

to create Hizballah in late 1982. Iranian goals

in Lebanon appear to be less revolutionary and more pragmatic today. Iran

appears willing to reap the additional political benefits of an Israeli

withdrawal and cease its armed struggle through its Hizballah proxy. Iranian Minister of Culture Ayatollah Mohajerani said as much

in April 1998, "If Israel withdraws from southern Lebanon within a security

framework to defined, secure borders, there will be no further need for

Hizballah oppositionist activities in southern Lebanon."[xx] Hizballah: Liberate LebanonAfter quietly

organizing itself in the wake of Israel's 1982 invasion of Lebanon, the

"Party of God" (hizballah in

Arabic), issued its manifesto in February 1985.

In it, Hizballah declared its pan-Islamic character, allegiance to

Khomeini's Iran, and hatred of Israel and its patron, the United States.

The manifesto legitimized armed struggle:

"Freedom is not freely given or granted, but it is retrieved through

the exertion of souls and blood. We

can no longer be patient for we have been patient for tens of years."[xxi]

Hizballah's campaign has included hostage taking and the destruction of

the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut as well as its guerrilla war against Israel

in the South. Hizballah

became the Shia standard bearer in the fight against the IDF after Amal's

power peaked in 1985. Hizballah

gained increasing popular support as Amal moved into the political mainstream.[xxii]

By the 1990s, Hizballah guerrillas were the primary force fighting Israel

in southern Lebanon earning them "recognition" during American mediation

efforts to end Israel's "Operation Accountability."

The April 26, 1996 Understandings went even further by implicitly

legitimizing Hizballah's right to attack Israeli forces in Lebanon. Hizballah is

moderating its public image. With

Iranian support, Hizballah has established itself "as the country's only

effective means of resistance, earning it some respect from across Lebanon's

fractured political spectrum."[xxiii]

Iran has sought to capitalize on that respect and has redirected some of

its support of Hizballah to establishing schools, hospitals and other social

services in Shia communities. Hizballah

has moved into the mainstream political life in Lebanon as a political party

with representatives in Parliament. Hizballah

has learned to adapt to the changing domestic and international political

climate as well, even though its ideology has not officially changed much since

its 1985 manifesto.[xxiv]

The deputy chief of Hizballah's political bureau reportedly said,

"There's a difference between ... ideological beliefs and ... political

stands."[xxv]

Hizballah realizes its war with Israel serves a purpose for its patrons,

Syria and Iran. Once that purpose is no longer served, Hizballah understands

its role must change, much the same as Amal's did before it.

As Hizballah

moves closer to the political mainstream, an unanswered question is whether

other factions will continue to launch attacks against Israel even if the IDF

withdraws. There are elements

within Hizballah that are more "radical" than others and may decide that

moderation is abandonment of the revolution.

It was just that kind of ideological rift in Amal that produced Hizballah

in 1982-83. Recent Israeli press

reports citing defense officials say that Hizballah is already in the midst of a

"violent split." Hizballah's

secretary-general Hasan Nasrallah heads the more moderate camp.

Subhi al-Tufayli, Hizballah's first secretary-general and former Amal

member leads the other camp. The

report says that Tufayli is more extreme than Nasrallah and has been advocating

a more "confrontational policy."[xxvi]

Tufayli launched a "Revolution of the Hungry" in July 1997 and led a

civil revolt in the Bekaa Valley demanding that the Lebanese government provide

more resources to the Shia living there, the poorest in the country.

Tufayli's actions have forced him out of the Hizballah mainstream, and

he has been in hiding since February 1998.

What role Tufayli and his followers could play in Lebanon after an

Israeli withdrawal is uncertain. There have

been reports recently that suggest Amal is reasserting itself in the conflict in

the South, especially since Israel began discussing withdrawal publicly.

These reports say that Amal cannot afford to let Hizballah take all the

credit for an Israeli pullout. Recently,

a booby-trapped videocassette that had been given to a SLA official exploded and

killed one and wounded several others in Lebanon near the Israeli border.

This incident was attributed to Amal and cited as evidence of one of its

"more spectacular" attacks aimed at regaining attention for Amal.

Moreover, the group reportedly has stepped up its conventional attacks on

IDF and SLA forces in southern Lebanon, which now average about one a day.[xxvii] The United

Nations Interim Forces in Lebanon (UNIFIL) and the Israel-Lebanon Monitoring

Group (ILMG) both currently serve in a "monitoring" capacity in southern

Lebanon. United NationsThe United

Nations Security Council established UNIFIL in 1978 with Resolution 425.

UNIFIL was chartered to confirm the withdrawal of Israeli forces, restore

international peace and security, and assist the Government of Lebanon in

regaining its effective authority in the area (see Appendix A).

The first contingent of UNIFIL troops arrived in Lebanon on March 23,

1978. Even though Israel withdrew

most of its troops by June 1978, it handed over its positions to its Lebanese

proxy, the SLA, not UNIFIL. Moreover,

Israel's 1982 invasion - which UNIFIL was powerless to prevent - left the UN

force behind the IDF's lines and limited its role to providing humanitarian

assistance and some protection to the local population.

Israel partially withdrew its forces in 1985 but maintained its

"security zone" along the border. Consequently,

UNIFIL has never fulfilled its mandate. It

has served as the UN's "eyes and ears" in the area and tries to prevent

its area of operations from being used by armed Lebanese groups to attack

Israeli forces. Both armed Lebanese

groups and the IDF have attacked UNIFIL forces over the years.

Currently, the force consisted of about 4500 soldiers provided by Fiji,

Finland, France, Ghana, Ireland, Italy, Nepal, India, and Poland.[xxviii]

UNIFIL, IDF/SLA, and LAF positions are shown in Figure 4.

Figure

4. UNIFIL, IDF/SLA, and LAF

Positions and Zones of Contro

MultilateralThe United

States, France, Israel, Lebanon, and Syria established the Israel-Lebanon

Monitoring Group (ILMG) in July 1996 as part of the "understanding" that

ended Israel's "Operation Grapes of Wrath."

The ILMG is independent of the United Nations.

France and the U.S. jointly chair the ILMG, alternating as chair and

co-chair every five months. The

group serves as a forum for hearing complaints of violation of the April 26,

1996 Understanding, which forbids attacks on civilians or attacks launched from

civilian areas. The goal of the

agreement is to protect civilian life and property and prevent escalation in

tensions. The members meet at

facilities provided by UNIFIL at its headquarters in Naqura, Lebanon, where the

ILMG reviews complaints, reports to member governments, and issues a press

statement. Because the ILMG

operates on the principle of unanimity, its statements tend to be factual

accounts of the complaining party's arguments without judgement. The ILMG

meets regularly to hear complaints of violation from Israel and Lebanon. After

more than three years, the April 26, 1996 Understanding appears to be holding.

Even though the ILMG has no enforcement power, it has helped to prevent

escalation that has proved so damaging in the past.

One example came after a recent Israeli attack on a senior Shia militia

official. With approval of the Israeli inner cabinet, the IDF launched

a helicopter attack that killed a top Amal militia official in southern Lebanon

on August 25, 1998. Immediately

following the attack, Hizballah rocketed towns in northern Israel wounding at

least 19 people.[xxix]

Initial press reports linked the rocket attacks to the Israeli

assassination. Subsequent reports,

however, said that the Hizballah attack was in response to Israeli shelling of

Lebanese villages during the same timeframe.[xxx]

Regardless of the reason for the rocket attack, in the past Israel did

not tolerate attacks on northern Israel and historically has responded with

military operations against Hizballah targets in Lebanon.

This time, the ILMG convened on August 31, 1998 to discuss the incident

and no escalation was reported. The

monitoring group has apparently forced the IDF to limit its operations to avoid

civilian casualties. An Israeli

artillery commander in Lebanon recently said that he has "... clear

instructions not to fire within 500 meters of any settlement," and added,

"There are very few places where I can fire freely."[xxxi]

At a minimum, the ILMG's continued existence - the only forum where

Israeli, Lebanese, and Syrian government representatives meet - demonstrates

commitment of the parties to cooperate and keep this line of communication open.

Recent Israeli Proposals for Withdrawal Israel's

April 1998 acceptance of UNSCR 425 prompted much discussion over when and how

the IDF might withdraw from Lebanon. At

the time, Israel publicly floated two approaches: ·

One, supported by Prime Minister

Benjamin Netanyahu and Defense Minister Yitzhak Mordechai, was based on

bilateral negotiations with Lebanon. An

IDF withdrawal was dependent on security guarantees to be made by the Lebanese

government in Beirut. Lebanese and

Syrian government officials responded that Resolution 425 could not be

negotiated and that Lebanon would not enter into any discussions over it.

Resolution 425 calls for Israel to immediately withdraw its forces and

does not provide for Lebanese security guarantees.

Moreover, Syria has no interest in allowing the Lebanese government to

negotiate with Israel bilaterally and insists that any discussion of IDF

withdrawal from Lebanon be tied to an Israeli withdrawal from the Golan Heights

as part of comprehensive peace negotiations.[xxxii]

Further, Syria may be concerned that if an IDF pullback withdrawal occurs

there will be calls to remove its own forces from Lebanon. ·

Then Infrastructure Minister Ariel

Sharon - the former Defense Minister who launched Israel's 1982 invasion of

Lebanon - championed the second idea that called for a unilateral, staged

pullout. Without explicit Lebanese

and Syrian security guarantees, a unilateral IDF withdrawal is fraught with

complications and is a non-starter, according to the views of some Israeli

analysts. A unilateral withdrawal

"... will not only result in perennial instability in the region, with

Israeli forces popping in and out of Lebanon each time there is a [rocket]

attack, but also in the mass slaughter of Israel's [South Lebanon Army]

allies."[xxxiii] For the

purposes of this paper, a complete Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon is assumed.

This study is based on conditions in early 1999 and is an assessment of

potential cooperative monitoring scenarios and does not try to predict the

likelihood or form of an IDF pullback. The

underlying assumption is that without a formal or informal political agreement

between Israel, Lebanon, and most likely Syria, there will be no withdrawal

scenario in which cooperative monitoring could be practical.

Moreover, all parties are assumed to have an interest in making the

agreement and any subsequent monitoring program work. Any formal or

informal agreement would probably include the following provisions: ·

Complete withdrawal of the IDF from

southern Lebanon ·

A cease-fire by Hizballah and

potentially the withdrawal of its units from southern Lebanon ·

Re-establishment of a Lebanese Army

presence in southern Lebanon ·

Disbanding of the South Lebanon Army ·

An understanding that Syria would not

move its military forces into areas vacated by the IDF Given the

mutual distrust of the participants, cooperative monitoring (possibly with third

party assistance) might be seen as a way to establish an environment that is

acceptable to all parties. In

addition, organized cooperation would act to build confidence between the

parties. Cooperative Monitoring Options IntroductionCooperative monitoring involves collecting, analyzing, and sharing agreed information among parties to an agreement. Cooperative monitoring systems typically rely on the use of commercially available sensor technology. When combined with techniques for data management and analysis, these technologies become useful tools for implementing security-related agreements. Cooperative monitoring systems should have the following three features:

This section presents and assesses a spectrum of cooperative monitoring options that might be implemented in southern Lebanon. The monitoring regimes are based on the assumption that a political agreement has been achieved and Israeli withdrawal has occurred. The participants in the cooperative monitoring process would include, as a minimum, Lebanon and Israel. Israel has an interest in a stable Lebanese government in control of southern Lebanon. Consequently, in some circumstances, Israel may benefit from an enhancement of the capability of the Lebanese security forces. The provision of new equipment and technical training to the LAF could provide a basis for cooperative monitoring of southern Lebanon by Israel and Lebanon. Additional participants could include other countries presently involved: Syria, France, and the U.S. Non-state players such as the Shia militias are not expected to be official parties to an agreement for withdrawal. Three conceptual monitoring regimes were developed to address the security goals of the participants, each requiring increasing levels of cooperation: a low cooperation regime, a medium cooperation regime, and a high cooperation regime. These conceptual regimes are intended to stimulate discussion and to define a spectrum of options for cooperative monitoring. They are not exclusive and other regimes may fall between these three options. Possible

Monitoring Options

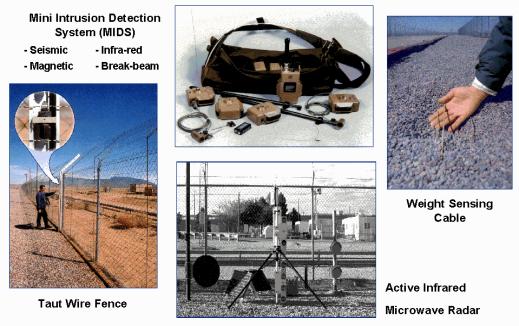

Given the history of the conflict in southern Lebanon, there may be no formal agreement. The Israelis are concerned about rocket and mortar attacks and infiltration into Israel. The Lebanese and Syrians are concerned about another Israeli movement into Lebanon. Thus, there are three physical objectives of a cooperative monitoring system in southern Lebanon: 1) detect significant incursions by conventional forces into southern Lebanon, 2) detect crossings of the Israel-Lebanon border, and 3) detect military or paramilitary activities that could lead to cross-border incursions or attacks. The system needs to have a significant, although not absolute, probability of detecting these activities. The cooperative monitoring system is intended to serve as a neutral system that supplements national means. Israel will certainly continue to use its national means to monitor southern Lebanon. Syria will do the same, although its capability is likely to be less sophisticated than Israel's. The system would serve a constructive basis for engagement and confidence building by the parties in either a formal or informal agreement. In addition, it would act as a deterrent to violations and provide confidence to Israel and Syria that the Lebanese Government is in control of the South. The observables[1] that a cooperative monitoring system should detect are movement by military or paramilitary forces on foot or by vehicle toward and across the border and threatening paramilitary activity within southern Lebanon. Detection of large numbers of vehicles associated with conventional military movements is much easier than detecting small numbers of paramilitary members with light weapons. A list of the monitoring options considered in this report follows: · Patrols · Manned and unmanned observation posts with technical sensors · Overflights using Unmanned Air Vehicles (UAVs) · Checkpoint monitoring using sensors that detect contraband aboard vehicles · Fence, seismic, magnetic, acoustic, and weight sensing unattended ground sensors (UGS) A number of other options were considered but rejected. Commercial satellite imagery was assessed to be too unresponsive to deal with the situation in southern Lebanon, where the time available for detecting and responding to suspicious activity is very short. In addition, even the 1-meter resolution of new commercial satellites is insufficient to identify some violations. A violator may be a single person with short-range rockets mounted on a pack animal. Overflights using manned aircraft could detect violations, but UAVs are perceived as less intrusive and, thus, more acceptable. Sensors to detect air vehicles, such as radars, were considered to be unnecessary as well as too expensive. The following sections describe the three conceptual cooperative monitoring regimes. The monitoring options were chosen after consideration of the available types of monitoring technologies, cost, political acceptability and the tolerance for undetected violations. A Low Cooperation RegimeAs a first option, we discuss a regime designed such that minimal cooperation between Israel and Lebanon is required. This regime would involve the least infringement upon Lebanese sovereignty and might be the most the Lebanese government could accept politically. It would also require the least resources to implement. The emphasis of this regime is on strengthening the ability of the LAF to control the area, increasing Israel's confidence in the security of its northern border. There would be no multilateral monitoring organization with operational responsibilities, nor would there be real time sharing of data between Israel and Lebanon, except in one specific, limited case. Features of the Low Cooperation RegimeAn Enhanced Lebanese Military. The goal is to enhance the ability of the LAF to control southern Lebanon and to detect activities that might endanger an agreement. The LAF, supported by a reliable communications network, would operate a system of patrols, checkpoints and observation posts on natural avenues of movement to monitor movement in the area. The LAF observation posts (OPs) would be equipped with sensors and other technical tools to improve their capability to monitor adjacent terrain. Hardware would include night vision devices, ground surveillance radar, and unattended ground sensors (UGS) that report to the observation posts. Applicable UGS include seismic, magnetic, acoustic, or weight sensors and could monitor locations where local topography blocks direct observation from an OP. Figure 5 shows examples of various types of UGS. In addition, the sensor system can be designed to provide a permanent record of detections.

Figure 5. Representative Unattended Ground Sensors (UGS) Technology can enhance other LAF monitoring functions. Patrols would be equipped with night vision devices and a communications system integrated with the OP network. Global Positioning System (GPS) receivers would permit accurate navigation and position reporting. Checkpoints would be established on traffic routes within the southern Lebanon region. An effective communications net would be installed in southern Lebanon so that suspicious activity could be reported promptly up the Lebanese chain of command. Lateral communications between observation posts would be established. Due to the limited nature of cooperation in this scenario, the information collected by the OPs or other LAF monitoring activity would not be communicated directly to a multinational monitoring group or Israel. Joint Parallel Border Patrols. The LAF and IDF would conduct joint patrols on their respective side of the border. These patrols would move on parallel roads that follow the border and maintain visual contact and short-range communications with each other. Neither side would cross the border itself, and their respective commanders would maintain control of each part of the patrol. The purpose of this feature is to ensure joint knowledge of border incidents. The patrols would be equipped with night vision devices, GPS receivers for position reporting, short-range communications so they can maintain contact with each other, and long-range communications to report up their respective chains of command. A joint report would be filed at the end of each patrol. Enhanced Border Checkpoints. To enhance security at border crossings, checkpoints would receive new monitoring capabilities. Vehicle inspection equipment such as weighing devices, X-ray equipment, and explosive detectors would be installed. Each party would operate its own equipment and would not be required to share data. There would be two cooperative features, however. First, each party would have its own set of inspectors on its own side of the border. Television cameras would be installed so that the each side might view the activities of the other inspectors. This is to instill confidence that each side is fulfilling its duties in a conscientious manner. There would also be voice communication between the two sides at the crossings. The other cooperative feature is the exchange of lists of individuals who are to be stopped at the border. These lists would presumably come from the security services of both countries. Notification of Incidents. There would be standardized procedures for notification of incidents to the appropriate government authority. Notification of Military Activities. Significant military activities in the border region would be subject to notification requirements. Reportable activities would include movements of significant numbers of troops or weapons, construction of new military facilities, or exercises. The installation of direct communication links between the LAF and IDF would aid the implementation of this commitment. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Low Cooperation RegimeThe low cooperation regime would improve the ability of Lebanon to control its southern region. It would also provide some additional capability for the Israelis to detect border crossings. The main advantages of the low cooperation regime are political. It minimizes intrusion on Lebanese sovereignty. It also offers considerable incentives to the Lebanese in the form of improved security capabilities for their army. We believe these enhanced capabilities would give Israel more confidence in the ability of Lebanon to control its border. The major disadvantage of this regime is that it may make the Israelis feel that they are giving up a great deal for relatively little in return. They would lose the additional warning time that their occupation of southern Lebanon has given them. They would have to rely to some extent on Lebanon, in spite of their national means of monitoring, to provide early warning along the border region. In addition, the lack of a means for quick communications between the Lebanese and Israelis at the tactical level may lead to misunderstandings and contribute to incidents. A Medium Cooperation RegimeThe medium cooperation regime would have the following

features in addition to or in place of those described in the low cooperation

regime. Features of the Medium Cooperation RegimeA

Joint Monitoring Group (JMG). A

joint monitoring group with a permanent staff would act as a facilitator of

monitoring policy and procedures. It

would receive data and reports from both sides for archiving.

Regular reports from both sides would be given to the group.

Under this regime, the JMG would not have an operational role, nor would

it receive data in real time. The

JMG could be a bilateral Lebanese-Israeli activity, or all national parties

could be involved, including Syria. A Joint Cooperative Border Strip and Fence. As a counterpart to the present border fence, which is controlled by the Israelis, a second fence would be established on the Lebanese side of the border. This fence and the strip between it and the border, which might be up to 1 km wide, would be monitored and the data would be sent directly to local Lebanese and Israeli officials. Possible sensors include fence motion sensors and UGS to detect movement within the intervening strip. Sensor reports would be archived by the JMG. The joint parallel border patrols could take place within the strip, or the LAF could patrol there alone with an IDF patrol on the Israeli side of the border. The fence would provide the Lebanese with a measure of control over border crossings and complement the Israeli fence. Enhanced Checkpoints in southern Lebanon. Internal checkpoints in southern Lebanon would be enhanced with the same technology used in the border checkpoints in the low cooperation regime. Reports would be sent to the JMG for archiving. A Cooperative Communication Net between OPs. While direct data sharing would not be implemented under this regime, a voice communication net between OPs that included Israeli participation would be established. This would permit better responses to indications of activity and could prevent misunderstandings that could cause incidents. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Medium Cooperation RegimeThe medium cooperation regime offers more capability to detect activity in southern Lebanon than the low cooperation regime. In particular, the cooperatively monitored border strip offers more assurance of detecting border crossings and gives the parties more time to respond. In addition, the expanded communication net can help avert misunderstandings that could contribute to an incident. Personnel in the border region could communicate much faster than if all communications were at the senior commander level. There is a benefit in the establishment of a multilateral group to help facilitate the agreement and serve as a repository for information. This regime would cost more than the low cooperation regime. Also, the introduction of the JMG as a "third party" might complicate acceptance. A High Cooperation RegimeThe

high cooperation regime would have the following features in addition to or in

place of those described in the medium cooperation regime. Features of the High Cooperation RegimeA

Joint Monitoring Group with Operational Responsibilities.

The role of the JMG would be expanded to include responsibility

for operating and maintaining the cooperative monitoring equipment. As before, the group would be multi-national in character and

include representatives from all parties to the agreement.

Data from sensors and reports from observers would be sent in real time

to a central site. From there,

reports would be sent to Israeli and Lebanese officials.

Any necessary response could be coordinated from this central site as

well. Joint Border Patrols. The joint border patrols would be supervised and tracked by the JMG using real time communications. The patrols would issue a report to the JMG, which in turn would include this information in periodic reports of normal activity and incident reports to the parties to the agreement. Cooperative Border Fence. The sensors associated with the cooperative fence in the border strip would transmit data in real time to the JMG. Observation Posts. The OPs would use real time communications links to report data directly to the JMG. This would include both voice messages from manned OPs, sensor data from UGS, and data from imaging devices. Cooperative UAV Patrols. Several UAVs could be operated and maintained by the JMG. They would be used for occasional surveys and for quick response to reports from the OPs and patrols. The UAVs would be based at the center and would be maintained by the JMG. A possible candidate for this role is the Israel Aircraft Industries Pioneer UAV. The Pioneer is a relatively old system that has been widely exported. A picture of a Pioneer is shown in Figure 6. Possible sensors for monitoring are video cameras and thermal imagers. This would permit day and night operation and would create a permanent record of images. Photo

courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense JMG

reports. The JMG would issue judgements and reports on

activity in the border region relevant to the terms of an agreement.

These would be transmitted to the parties of the agreement through their

representatives in the JMG. Advantages and Disadvantages of the High Cooperation RegimeThis regime would require the most cooperation by all parties and could build on the success of the Israel-Lebanon Monitoring Group. The JMG would provide all parties with a more independent picture of the activities in the border region, which could prevent misunderstandings and improve confidence. In addition, the UAV capability would permit quick responses to reports of suspicious activities The main disadvantage of the high cooperation regime is its requirement for an active multi-national group with operational responsibilities and the significantly higher costs associated with it. The inherent intrusiveness of a JMG may prove too much for Lebanese and/or Israeli acceptance. Having to filter data though the JMG may make response time to suspicious activity slower than would be acceptable to either Israel or Lebanon.

Comparison of the Three RegimesTable 1. Functional Components of the Three Cooperative Monitoring Regimes

National MeansCooperative monitoring is not intended to replace national means used by the parties. The monitoring system would complement national means that monitor an agreement. The Role of UN PeacekeepersThe

effectiveness of UNIFIL is limited by Israeli reluctance to cooperate.

An Israeli withdrawal might lead to a greater role for UNIFIL.

UNIFIL might confirm the withdrawal of the IDF and perform interim

monitoring until the LAF is able to regain control of southern Lebanon and/or

cooperative monitoring is implemented

Each of the key players involved in Lebanon has specific goals that will affect their security decisions:

An agreement that included an Israeli withdrawal and the reestablishment of effective Lebanese military control of the Israel-Lebanon border could contribute to the goals of the various parties. Cooperative monitoring could help build confidence among the parties that their respective security interests were being addressed. Three possible cooperative monitoring regimes have been described in this report, each requiring different levels of cooperation. Each has relative advantages and disadvantages. A feature of each regime is that it permits Israel to, in effect, monitor the Lebanese monitors in southern Lebanon and gain confidence that they are performing their mission. In general, the regimes with less cooperation may be more attractive to the Lebanese, as the perceived infringement on their sovereignty is likely to be less. The Israelis may prefer a relatively high level of cooperation, as that would give them more information about activities in southern Lebanon that potentially threaten their security. Appendix A: Relevant United Nations Resolutions RESOLUTION

425 (1978) Adopted

by the Security Council at its 2074th meeting on

19 March 1978, The Security

Council, Taking note

of the letters from the Permanent Representative of Lebanon and from the

Permanent Representative of Israel, Having heard

the statement of the Permanent Representatives of Lebanon and Israel, Gravely

concerned at the deterioration of the situation in the Middle East and its

consequences to the maintenance of international peace, Convinced

that the present situation impedes the achievement of a just peace in the Middle

East, 1. Calls for

strict respect for the territorial integrity, sovereignty and political

independence of Lebanon within its internationally recognized boundaries; 2. Calls upon

Israel immediately to cease its military action against Lebanese territorial

integrity and withdraw forthwith its forces from all Lebanese territory; 3. Decides,

in the light of the request of the Government of Lebanon, to establish

immediately under its authority a United Nations interim force for southern

Lebanon for the purpose of confirming the withdrawal of Israeli forces,

restoring international peace and security and assisting the Government of

Lebanon in ensuring the return of its effective authority in the area, the Force

to be composed of personnel drawn from Member States; 4. Requests

the Secretary-General to report to the Council within twenty-four hours on the

implementation of the present resolution. RESOLUTION

426 (1978) Adopted

by the Security Council at its 2075th meeting On

19 March 1978,

The Security Council,

1. Approves the report of

the Secretary-General on the implementation of Security Council resolution 425

(1978), contained in document S/12611 of 19 March 1978, 2. Decides

that the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon shall be established in

accordance with the above-mentioned report for an initial period of six months,

and that it shall continue in operation thereafter if required, provided the

Security Council also decides. RESOLUTION

427 (1978) Adopted

by the Security Council at its 2076th meeting On

3 May 1978

The Security Council,

Having considered the letter dated 1 May 1978 from the Secretary-General

to the President of the Security Council,

Recalling its resolutions 425 (1978) and 426 (1978) of 19 March 1978, 1. Approves

the increase in the strength of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon

requested by the Secretary-General from 4,000 to approximately 6,000 troops; 2. Takes note

of the withdrawal of Israeli forces that has taken place so far; 3. Calls upon

Israel to complete its withdrawal from all Lebanese territory without further

delay; 4. Deplores

the attacks on the United Nations Forces that have occurred and demands full

respect for the United Nations Force from all parties in Lebanon. Appendix B: Text of April 26, 1996

Cease-fire Understanding "The United

States understands that after discussions with the governments of Israel and

Lebanon, and in consultation with Syria, Lebanon and Israel will ensure the

following: 1. Armed

groups in Lebanon will not carry out attacks by Katyusha rockets or by any kind

of weapon into Israel. 2. Israel and

those cooperating with it will not fire any kind of weapon at civilians or

civilian targets in Lebanon. 3. Beyond

this, the two parties commit to ensuring that under no circumstances will

civilians be the target of attack and that civilian populated areas and

industrial and electrical installations will not be used as launching grounds

for attacks. 4. Without

violating this understanding, nothing herein shall preclude any party from

exercising the right of self-defense. A Monitoring

Group is established consisting of the United States, France, Syria, Lebanon and

Israel. Its task will be to monitor

the application of the understanding stated above.

Complaints will be submitted to the Monitoring Group. In the event

of a claimed violation of the understanding, the party submitting the complaint

will do so within 24 hours. Procedures

for dealing with the complaints will be set by the Monitoring Group. The United

States will also organize a Consultative Group, to consist of France, the

European Union, Russia and other interested parties, for the purpose of

assisting in the reconstruction needs of Lebanon. It is

recognized that the understanding to bring the current crisis between Lebanon

and Israel to an end cannot substitute for a permanent solution. The United States understands the importance of achieving a

comprehensive peace in the region. Toward this

end, the United States proposes the resumption of negotiations between Syria and

Israel and between Lebanon and Israel at a time to be agreed upon, with the

objective of reaching comprehensive peace. The United

States understands that it is desirable that these negotiations be conducted in

a climate of stability and tranquility. This

understanding will be announced simultaneously at 1800 hours, April 26, 1996, in

all countries concerned with implementation at 0400 hours, April 27, 1996."[xxxiv] References

* Also known as the "security cabinet," this group is comprised of 11 of the Prime Minister's 18 Cabinet ministers. [1] Observables are objects or activities that are distinctive and can be used to detect and identify subjects of interest to a monitoring system. [i] Beate Hamizrachi, The Emergence of the South Lebanon Security Belt. (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1988). [ii] Richard B. Parker, "Kawkaba and the South Lebanon Imbroglio: A Personal Recollection, 1977-1978," The Middle East Journal, Volume 50, Number 4, Autumn 1996, p. 548. [iii] Charles Winslow, Lebanon: War and Politics in a Fragmented Society. (New York: Routledge, 1996). [iv] Augustus Richard Norton, "Hizballah: From Radicalism to Pragmatism?" Middle East Policy, Volume V, Number 4, January 1998. [v] Ezer Weizman, The Battle for Peace. (Jerusalem: Edanim Publishers, 1981), p. 247 as quoted in Hamizrachi. [vi] Jimmy Carter, The Blood of Abraham. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1985). p. 96. [vii] Helen Chapin Metz, editor, Israel: A Country Study. (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1990) pp. 262-266; and Ze'ev Schiff and Ehud Ya'ari, Israel's Lebanon War. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984) , pp. 102-103. [viii] "Lebanese Sources Say SLA Morale 'Particularly Low'," Ma'ariv, September 9, 1998 as translated by the Foreign Broadcast Information Service. [ix] Patrick Seale, Asad of Syria: The Struggle for the Middle East. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), p. 268. [x] Seale, p. 276, 283. [xi] Seale, p. 288. [xii] Augustus Richard Norton, "Lebanon After Ta'if: Is the Civil War Over?" Middle East Journal, Volume 45, Number 3, Summer 1991. [xiii] CIA World Factbook, 1997. [xiv] R. Jeffrey Smith, "Christopher to Pressure Syria to Block Cargo to Hizballah," The Washington Post, July 31, 1993, p. A14. [xv] CNN Interactive, "Syria rejects Israeli peace talk overtures," August 7, 1996. [xvi] Fouad Ajami, The Vanished Imam, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986). p. 168. [xvii] Norton. [xviii] Magnus Ranstorp, Hizballah in Lebanon, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997) pp. 30-31. [xix] Ranstorp, p. 33. [xx] Haaretz, Internet version, "Iranian, Syrian Plans for Hizballah Examined," April 1, 1998 as translated by the Foreign Broadcast Information Service. [xxi] As quoted in Jaber, p. 58. [xxii] Norton. [xxiii] Douglas Jehl, "Lebanon Rebel Fighters Gain Stature, But for How Long?" The New York Times, April 21, 1996, Section 1, page 1. [xxiv] Jaber, p. 71. [xxv] Jehl. [xxvi] Steve Rodan, "Syria, Iran Seen Encouraging Split Inside Hizballah," The Jerusalem Post, August 6, 1998, p. 4. [xxvii] David Rudge, "Amal Gets a Boost in its Battle with Hizballah," The Jerusalem Post, Internet Edition, August 26, 1998. [xxviii] Department of Public Information, United Nations, "United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon," from the Internet. Information updated as of June 16, 1998; and Peacekeeping & International Relations, "Global Situation Report of Current United Nations Peacekeeping and Related Operations," Volume 27, Number 3, p.9. [xxix] Jerusalem Qol Yisra'el radio, 1900 GMT, August 25, 1998 as translated by the Foreign Broadcast Information Service; and Alik Maor, "Guerrilla's Death Sparks 'Deterrent'," Associated Press, August 26, 1998. [xxx] Beirut Radio Lebanon, 0430 GMT August 26, 1998 as translated by the Foreign Broadcast Information Service. [xxxi] Alan Philps, "Israel's Military Might Cannot Quell Lebanese," Telegraph, September 23, 1998, Internet version. [xxxii] Zvi Bar'el, "In Lebanon, It's Time for Meddlers to Pay the Piper," Ha'aretz, April 1, 1998. Internet English version. [xxxiii] Hirsh Goodman, "Think to Win," The Jerusalem Report, June 22, 1998, p. 56. [xxxiv] Information Division, Israel Foreign Ministry, Jerusalem. Distribution 1 MS 1371 M. G. Vannoni, 5338 1 MS 1371 J. N. Olsen, 5338 1 MS 1371 D. Barber, 5338 1 MS 1371 F. O. Luetters, 5338 1 MS 1373 A. L. Pregenzer, 5341 1 MS 1373 R. M. Salerno, 5341 1 MS 1373 K. L. Biringer, 5341 1 MS 0419 W. C. Hines, 9701 1 MS 0415 K. J. Almquist, 9711 1 MS 0417 W. H. Ling, 9713 1 MS 0425 S. K. Fraley, 9715 5 MS 0425 L. C. Trost, 9715 125 MS 1373 CMC Library, 5391 1 MS 9018 Central Tech Files, 8940-2 2 MS 0899 Technical Library, 4916 1 MS 0619 Review & Approval Desk, 4912

25 Charles Spain Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory P.O. Box 808, (mailstop L-387) Livermore, CA 94551 1 Jerry Mullens Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory P.O. Box 808, (mailstop L-387) Livermore, CA 94551 5 Michael Yaffe NP/RA Department of State 2201 C St. Street NW Washington, D.C. 20451

|

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|