|

RDL Homepage |

Table of Contents |

Document Information |

Download Instructions |

LESSON 3

MILITARY OPERATIONS ON URBAN TERRAIN (DEFENSE)

OVERVIEW

LESSON DESCRIPTION:

In this lesson you will learn to perform a specific task required in planning for and conducting a defensive operation on urbanized terrain.

TERMINAL LEARNING OBJECTIVE:

| ACTION: | Identify the employment capabilities and limitations of combat, combat support, and combat service support assets available to a Battalion Task Force engaged in MOUT defense. |

| CONDITION: | Given extracts of doctrinal literature, a tactical situation for a battalion TF S3, and a series of multiple-choice questions relating to Threat force offensive doctrine. |

| STANDARD: | To demonstrate competency of the task, you must achieve a minimum of 70% on the subcourse examination. |

| REFERENCES: | The material contained in this lesson was derived from the following publications: FM 34-130, FM 90-10-1, and FM 100-2-2. |

INTRODUCTION

Successful combat operations in built-up areas depend on the proper employment of the rifle squad. Each member must be skilled in the techniques of combat in built-up areas: selecting and using firing positions, navigating in built-up areas, and camouflaging. Soldiers must remember to remain in buddy teams when moving through a MOUT environment.

CHARACTERISTICS AND CATEGORIES OF BUILT-UP AREAS

One of the first requirements for conducting operations in built-up areas is to understand the common characteristics and categories of such areas.

1. Characteristics. Built-up areas consist mainly of man-made features such as buildings. Buildings provide cover and concealment, limit fields of observation and fire, and block movement of troops, especially mechanized troops. Thick-walled buildings provide ready-made, fortified positions. Thin-walled buildings that have fields of observation and fire may also be important. Another important aspect is that built-up areas complicate, confuse and degrade command and control.

a. Streets are usually avenues of approach. However, forces moving along streets are often canalized by the buildings and have little space for off-road maneuver. Thus, obstacles on streets in towns are usually more effective than those on roads in open terrain since they are more difficult to bypass.

b. Subterranean systems found in some built-up areas are easily overlooked but can be important to the outcome of operations. The include subways, sewers, cellars, and utility systems (Figure 3-1).

Figure 3-1. Underground systems.

2. Categories.

a. Built-up areas are classified into four categories:

(1) Villages (population of 3,000 or less).

(2) Strip areas (urban areas built along roads connecting towns or cities).

(3) Towns or small cities (population up to 100,000 and not part of a major urban complex).

(4) Large cities with associated urban sprawl (population in the millions, covering hundreds of square kilometers).

b. Each area affects operations differently. Villages and strip areas are commonly encountered by companies and battalions. Towns and small cities involve operations of entire brigades or divisions. Large cities and major urban complexes involve units up to corps size and above.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Several considerations are addressed herein concerning combat in built-up areas.

1. Battles in Built-Up Areas. Battles in built-up areas usually occur when:

a. A city is between two natural obstacles and there is no bypass.

b. The seizure of a city contributes to the attainment of an overall objective.

c. The city is in the path of a general advance and cannot be surrounded or bypassed.

d. Political or humanitarian concerns require the seizure or retention of a city.

2. Target Engagement. In the city, the ranges of observation and fields of fires are reduced by structures as well as by the dust and smoke of battle. Targets are usually briefly exposed at ranges of 100 meters or less. As a result, combat in built-up areas consists mostly of close, violent combat. Infantry troops will use mostly light and medium antitank weapons, automatic rifles, machine guns, and hand grenades. Opportunities for using antitank guided missiles (ATGMs) are rare because of the short ranges involved and the many obstructions that interfere with missile flight.

3. Small-Unit Battles. Units fighting in built-up areas often become isolated, making combat a series of small-unit battles. Soldiers and small-unit leaders must have the initiative, skill, and courage to accomplish their missions while isolated from their parent units. A skilled, well-trained defender has tactical advantages over the attacker in this type of combat. He occupies strong static positions, whereas the attacker must be exposed in order to advance. Greatly reduced line-of-sight ranges, built-in obstacles, and compartmented terrain require the commitment of more troops for a given frontage. The troop density for both an attack and defense in built-up areas can be as much as three to five times greater than for an attack or defense in open terrain. Individual soldiers must be trained and psychologically ready for this type of operation.

4. Munitions and Special Equipment. Forces engaged in fighting in built-up areas use large quantities of munitions because of the need for reconnaissance by fire, which is due to short ranges and limited visibility. LAWs or AT-4s, rifle and machine gun ammunition, 40-mm grenades, hand grenades, and explosives are high-usage items in this type of fighting. Units committed to combat in built-up areas also must have special equipment such as grappling hooks, rope, snaplinks, collapsible pole ladders, rope ladders, construction material, axes, and sandbags. When possible, those items should be either stockpiled or brought forward on-call, so they are easily available to the troops.

5. Communications. Urban operations require centralized planning and decentralized execution. Therefore, communications play an important part. Commanders must trust their subordinates' initiative and skill, which can only occur through training. The state of a unit's training is a vital, decisive factor in the execution of operations in built-up areas.

a. Wire is the primary means of communication for controlling the defense of a city and for enforcing security. However, wire can be compromised if interdicted by the enemy.

b. Radio communication in built-up areas is normally degraded by structures and a high concentration of electrical power lines. Many buildings are constructed so that radio waves will not pass through them. The new family of radios may correct this problem, but all units within the built-up area may not have these radios. Therefore, radio is an alternate means of communication.

c. Visual signals may also be used but are often not effective because of the screening effects of buildings, walls, and so forth. Signals must be planned, widely disseminated, and understood by all assigned and attached units. Increased noise makes the effective use of sound signals difficult.

d. Messengers can be used as another means of communication.

6. Stress. A related problem of combat in built-up areas is stress. Continuous close combat, intense pressure, high casualties, fleeting targets, and fire from a concealed enemy produce psychological strain and physical fatigue for the soldier. Such stress requires consideration for the soldiers' and small-unit leaders' morale and the unit's esprit de corps. Stress can be reduced by rotating units that have been committed to heavy combat for long periods.

7. Restrictions. The law of war prohibits unnecessary injury to noncombatants and needless damage to property. This may restrict the commander's use of certain weapons and tactics. Although a disadvantage at the time, this restriction may be necessary to preserve a nation's cultural institutions and to gain the support of its people. Units must be highly disciplined so that the laws of land warfare and rules of engagement (ROE) are obeyed. Leaders must strictly enforce orders against looting and expeditiously dispose of violations against the UCMJ.

8. Fratricide Avoidance. The overriding consideration in any tactical operation is the accomplishment of the mission. Commanders must consider fratricide in their planning process because of the decentralized nature of execution in the MOUT environment. However, they must weigh the risk of fratricide against losses to enemy fire when considering a given course of action. Fratricide is avoided by doctrine; by tactics, techniques, and procedures; and by training.

a. Doctrine. Doctrine provides the basic framework for accomplishment of the mission. Commanders must have a thorough understanding of US, joint, and host nation doctrine.

b. Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP). TTP provide a "how-to" that everyone understands. TTP are disseminated in doctrinal manuals and SOPs.

(1) Tactics. Tactics is the employment of units in combat or the ordered arrangement and maneuver of units in relation to each other and or the enemy in order to use their full potential.

(2) Techniques. Techniques are the general and detailed methods used by troops or commanders to perform assigned missions and functions. Specifically, techniques are the methods of using weapons and personnel. Techniques describe a method, but not the only method.

(3) Procedures. Procedures are standard, detailed courses of action that describe how to accomplish a task.

(4) Planning. A simple, flexible maneuver plan that is disseminated to the lowest level of command will aid in the prevention of fratricide. Plans should make the maximum possible use of SOPs and battle drills at the user level. They should incorporate adequate control measures and fire support planning and coordination to ensure the safety of friendly troops and allow changes after execution begins.

(5) Execution. The execution of the plan must be monitored, especially with regard to the location of friendly troops and their relationship to friendly fires. Subordinate units must understand the importance of accurately reporting their position.

c. Training. The most important factor in the prevention of fratricide is individual and collective training in the many tasks that support MOUT.

(1) Situational Awareness. Well-trained soldiers accomplish routine tasks instinctively or automatically. This allows them to focus on what is happening on the battlefield. They can maintain an awareness of the relative location of enemy and friendly forces.

(2) Rehearsal. Rehearsal is simply training for the mission at hand. Commanders at every level must allow time for this critical task.

(3) Train to Standard. Soldiers that are trained to the Army standard are predictable. This predictability will be evident to any NCO or officer who may be required to lead them at a moments notice or who is observing their maneuvers to determine if they are friend or foe.

FIRING POSITIONS

Whether a unit is attacking, defending, or conducting retrograde operations, its success or failure depends on the ability of the individual soldier to place accurate fire on the enemy with the least exposure to return fire. Consequently, the soldier must immediately seek and properly use firing positions.

1. Hasty Firing Position. A hasty firing position is normally occupied in the attack or the early stages of the defense. It is a position from which the soldier can place fire upon the enemy while using available cover for protection from return fire. The soldier may occupy it voluntarily, or he may be forced to occupy it due to enemy fire. In either case, the position lacks preparation before occupation. Some of the more common hasty firing positions in a built-up area and techniques for occupying them are: corners of buildings, firing from behind walls, firing from windows, firing from unprepared loopholes, and firing from the peak of a roof.

a. Corners of buildings. The corner of a building provides cover for a hasty firing position if used properly.

(1) The firer must be capable of firing his weapon both right- and left-handed to be effective around corners. A common error made in firing around corners is firing from the wrong shoulder. This exposes more of the firer's body to return fire than necessary. By firing from the proper shoulder, the firer can reduce the target exposed to enemy fire.

(2) Another common mistake when firing around corners is firing from the standing position. The firer exposes himself at the height the enemy would expect a target to appear, and risks exposing the entire length of his body as a target for the enemy.

b. Walls. When firing behind walls, the soldier must fire around cover - not over it (Figure 3-2).

Figure 3-2. Soldier firing around cover.

c. Windows. In a built-up area, windows provide convenient firing ports. The soldier must avoid firing from the standing position since it exposes most of his body to return fire from the enemy and could silhouette him against a light-colored interior beyond the window. This is an obvious sign of the firer's position, especially at night when the muzzle flash can easily be observed. In using the proper method of firing from a window (Figure 3-3), the soldier is well back into the room to prevent the muzzle flash from being seen, and he is kneeling to limit exposure and avoid silhouetting himself.

Figure 3-3. Soldier firing from window.

d. Loopholes. The soldier may fire through a hole in the wall and avoid windows (Figure 3-4). He stays well back from the loophole so the muzzle of the weapon does not protrude beyond the wall, and the muzzle flash is concealed.

Figure 3-4. Soldier firing from loophole.

e. Roof. The peak of a roof provides a vantage point for snipers that increases their field of vision and the ranges at which they can engage targets (Figure 3-5). A chimney, a smokestack, or any other object protruding from the roof of a building can reduce the size of the target exposed and should be used.

Figure 3-5. Soldier firing from oeak of a roof.

f. No Position Available. When the soldier is subjected to enemy fire and none of the positions mentioned above are available, he must try to expose as little of himself as possible. When a soldier in an open area between buildings (a street or alley) is fired upon by enemy in one of the buildings to his front and no cover is available, he should lie prone as close as possible to a building on the same side of the open area as the enemy. To engage the soldier, the enemy must then lean out the window and expose himself to return fire.

g. No Cover Available. When no cover is available, target exposure can be reduced by firing from the prone position, by firing from shadows, and by presenting no silhouette against buildings.

2. Prepared Firing Position. A prepared firing position is one built or improved to allow the firer to engage a particular area, avenue of approach, or enemy position, reducing his exposure to return fire. Examples of prepared positions include: barricaded windows, fortified loopholes, sniper positions, anti-armor positions, and machine gun positions.

a. The natural firing port provided by windows can be improved by barricading the window, leaving a small hole for the firer's use (Figure 3-6). The barricading may be accomplished with materials torn from the interior walls of the building or any other available material. When barricading windows, avoid:

(1) Barricading only the windows that will be used as firing ports. The enemy will soon determine that the barricaded windows are firing positions.

Figure 3-6. Window firing position.

(2) Neat, square, or rectangular holes that are easily identified by the enemy. A barricaded window should not have a neat, regular firing port. The window should keep its original shape so that the position of the firer is hard to detect. Firing from the bottom of the window gives the firer the advantage of the wall because the firing port is less obvious to the enemy. Sandbags are used to reinforce the wall below the window and to increase protection for the firer. All glass must be removed from the window to prevent injury to the firer. Lace curtains permit the firer to see out and prevent the enemy from seeing in. Wet blankets should be placed under weapons to reduce dust. Wire mesh over the window keeps the enemy from throwing in hand grenades.

b. Although windows usually are good firing positions, they do not always allow the firer to engage targets in his sector.

(1) To avoid establishing a pattern of always firing from windows, an alternate position is required such as the prepared loophole (Figure 3-7). This involves cutting or blowing a small hole into the wall to allow the firer to observe and engage targets in his sector.

(2) Sandbags are used to reinforce the walls below, around, and above the loophole. Two layers of sandbags are placed on the floor under the firer to protect him from an explosion on a lower floor (if the position is on the second floor or higher). A wall of sandbags, rubble, furniture, and so on should be constructed to the rear of the position to protect the firer from explosions in the room.

Figure 3-7. Prepared loopholes.

(3) A table, bedstead, or other available material provides overhead cover for the position. This prevents injury to the firer from falling debris or explosions above his position.

(4) The position should be camouflaged by knocking other holes in the wall, making it difficult for the enemy to determine which hole the fire is coming from. Siding material should be removed from the building in several places to make loopholes less noticeable.

c. A chimney or other protruding structure provides a base from which a sniper position can be prepared. Part of the roofing material is removed to allow the sniper to fire around the chimney. He should stand inside the building on the beams or on a platform with only his head and shoulders above the roof (behind the chimney). Sandbags placed on the sides of the position protect the sniper's flanks.

d. When the roof has no protruding structure to provide protection (Figure 3-8), the sniper position should be prepared from underneath on the enemy side of the roof. The position is reinforced with sandbags, and a small piece of roofing material should be removed to allow the sniper to engage targets in his sector. The missing piece of roofing material should be the only sign that a position exists. Other pieces of roofing should be removed to deceive the enemy as to the true sniper position. The sniper should be invisible from outside the building, and the muzzle flash must be hidden from view.

Figure 3-8. Sniper position.

e. Some rules and considerations for selecting and occupying individual firing positions are:

(1) Make maximum use of available cover and concealment.

(2) Avoid firing over cover; when possible, fire around it.

(3) Avoid silhouetting against light-colored buildings, the skyline, and so on.

(4) Carefully select a new firing position before leaving an old one.

(5) Avoid setting a pattern; fire from both barricaded and unbarricaded windows.

(6) Keep exposure time to a minimum.

(7) Begin improving a hasty position immediately after occupation.

(8) Use construction material for prepared positions that is readily available in a built-up area.

(9) Remember that positions that provide cover at ground level may not provide cover on higher floors.

f. In attacking a built-up area, the recoilless weapon and ATGM crews are severely hampered in choosing firing positions due to the backblast of their weapons. They may not have enough time to knock out walls in buildings and clear backblast areas. They should select positions that allow the backblast to escape such as corner windows where the round fired goes out one window and the backblast escapes from another. The corner of a building can be improved with sandbags to create a firing position (Figure 3-9).

Figure 3-9. Corner firing position.

g. The rifle squad during an attack on and in defense of a built-up area is often reinforced with attached antitank weapons. Therefore, the rifle squad leader must be able to choose good firing positions for the antitank weapons under his control.

h. Various principles of employing antitank weapons have universal applications such as: making maximum use of available cover; trying to achieve mutual support; and allowing for the backblast when positioning recoilless weapons, TOWs, Dragons, and LAWs or AT4s.

i. Operating in a built-up area presents new considerations. Soldiers must select numerous alternate positions, particularly when the structure does not provide cover from small-arms fire. They must position their weapons in the shadows and within the building.

j. Recoilless weapons and ATGMs firing from the top of a building can use the chimney for cover (Figure 3-10). The rear of this position should be reinforced with sandbags.

Figure 3-10. A recoilless weapon crew firing from a rooftop.

k. When selecting firing positions for recoilless weapons and ATGMs, make maximum use of rubble, corners of buildings, and destroyed vehicles to provide cover for the crew. Recoilless weapons and ATGMs can also be moved along rooftops to obtain a better angle in which to engage enemy armor. When buildings are elevated, positions can be prepared using a building for overhead cover (Figure 3-11). The backblast under the building must not damage or collapse the building or injure the crew.

Figure 3-11. Prepared positions using a building for overhead cover.

NOTE:

When firing from a slope, ensure that the angle of the launcher relative to the ground or firing platform is not greater than 20 degrees. When firing within a building, ensure the enclosure is at least 10 feet by 15 feet, is clear of debris and loose objects, and has windows, doors, or holes in the walls for the backblast to escape.

l. The machine gun has no backblast, so it can be emplaced almost anywhere. In the attack, windows and doors offer ready-made firing ports (Figure 3-12). For this reason, the enemy normally has windows and doors under observation and fire, which should be avoided. Any opening in walls that was created during the fighting may be used. When other holes are not present, small explosive charges can create loopholes (Figure 3-13). Regardless of what openings are used, machine guns should be within the building and in the shadows.

Figure 3-12. Employment of a machine gun in a doorway.

Figure 3-13. Use of a loophole with a machine gun.

m. Upon occupying a building, soldiers board up all windows and doors. By leaving small gaps between the slots, soldiers can use windows and doors as good alternative firing positions.

n. Loopholes should be used extensively in the defense. They should not be constructed in any logical pattern, nor should they all be at floor or table-top level. Varying their height and location makes them hard to pinpoint and identify. Dummy loopholes, shingles knocked off, or holes cut that are not intended to be used as firing positions aid in the deception. Loopholes located behind shrubbery, under doorjams, and under the eaves of a building are hard to detect. In the defense, as in the offense, a firing position can be constructed using the building for overhead cover.

o. Increased fields of fire can be obtained by locating the machine gun in the corner of the building or sandbagged under a building (Figure 3-14). Available materials, such as desks, overstuffed chairs, couches, and other items of furniture, should be integrated into the construction of bunkers to add cover and concealment (Figure 3-15).

Figure 3-14. Sandbagged machine gun emplacement under a building.

Figure 3-15. Corner machine gun bunker.

p. Although grazing fire is desirable when employing the machine gun, it may not always be practical or possible. When destroyed vehicles, rubble, and other obstructions restrict the fields of grazing fire, the gun can be elevated to where it can fire over obstacles. Therefore, firing from loopholes on second or third story may be necessary. A firing platform can be built under the roof (Figure 3-16) and a loophole constructed. Again, the exact location of the position must be concealed by knocking off shingles in isolated patches over the entire roof.

Figure 3-16. Firing platform built under roof.

3. Target Acquisition. Built-up areas provide unique challenges to units. Buildings mask movement and the effects of direct and indirect fires. The rubble from destroyed buildings, along with the buildings themselves, provide concealment and protection for attackers and defenders, making target acquisition difficult. A city offers definite avenues of approach that can easily be divided into sectors.

a. The techniques of patrolling and using observation posts apply in the city as well as in wooded terrain. These techniques enable units to locate the enemy, to develop targets for direct and indirect fires in the defense, and to find uncovered avenues of approach in the offense.

b. Most weapons and vehicles have distinguishing signatures. These come from design features or from the environment in which the equipment is used. For example, firing a tank main gun in dry, dusty, and debris-covered streets raises a dust cloud; a tank being driven in built-up areas produces more noise than one moving through an open field; soldiers moving through rubble on a street or in the halls of a damaged building create more noise than in a wooded area. Soldiers must recognize signatures so they can locate and identify targets. Seeing, hearing, and smelling assist in detecting and identifying signatures that lead to target location, identification, and rapid engagement. Soldiers must look for targets in areas where they are most likely to be employed.

c. Target acquisition must be continuous, whether halted or moving. Built-up areas provide both the attacker and defender with good cover and concealment, but it usually favors the defender because of the advantages achieved. This makes target acquisition extremely important since the side that fires first may win the engagement.

d. When a unit is moving and enemy contact is likely, the unit must have an overwatching element. This principle applies in built-up areas as it does in other kinds of terrain except that the overwatching element must observe both the upper floors of buildings and street level.

e. Stealth should be used when moving in built-up areas since little distance separates attackers and defenders. Only arm-and-hand signals should be used until contact is made. The unit should stop periodically to listen and watch, ensuring it is not being followed or that the enemy is not moving parallel to the unit's flank for an ambush. Routes should be carefully chosen so that buildings and piles of rubble can be used to mask the unit's movement.

f. Observation duties must be clearly given to squad members to ensure all-round security as they move. This security continues at the halt. All the senses must be used to acquire targets, especially hearing and smelling. Soldiers soon recognize the sounds of vehicles and people moving through streets that are littered with rubble. The smell of fuel, cologne, and food cooking can disclose enemy positions.

g. Observation posts are positions from which soldiers can watch and listen to enemy activity in a specific sector. They warn the unit of an enemy approach and are ideally suited for built-up areas. OPs can be positioned in the upper floors of buildings, giving soldiers a better vantage point than at street level.

h. In the defense, a platoon leader positions OPs for local security as ordered by the company commander. The platoon leader selects the general location but the squad leader sets up the OP (Figure 3-17). Normally, there is at least one OP for each platoon. An OP consists of two to four men and is within small-arms supporting range of the platoon. Leaders look for positions that have good observation of the target sector. Ideally, an OP has a field of observation that overlaps those of adjacent OPs. The position selected for the OP should have cover and concealment for units moving to and from the OP. The upper floors of houses or other buildings should be used. The squad leader should not select obvious positions, such as water towers or church steeples, that attract the enemy's attention.

Figure 3-17. Selection of OP location.

i. The soldier should be taught how to scan a target area from OPs or from his fighting positions. Use of proper scanning techniques enable squad members to quickly locate and identify targets. Without optics, the soldier searches quickly for obvious targets, using all his senses to detect target signatures. If no targets are found and time permits, he makes a more detailed search (using binoculars, if available) of the terrain in the assigned sector using the 50-meter method. First, he searches a strip 50 meters deep from right to left; then he searches a strip from left to right that is farther out, overlapping the first strip. This process is continued until the entire sector is searched. In the city core or core periphery where the observer is faced with multistory buildings, the overlapping sectors may be going up rather than out.

j. Soldiers who man OPs and other positions should employ target acquisition devices. These devices include binoculars, image intensification devices, thermal sights, GSR, remote sensors (REMs) and platoon early warning systems (PEWS). All of these devices can enhance the units ability to detect and engage targets. Several types of devices should be used since no single device can meet every need of a unit. A mix might include PEWS sensors to cover out-of-sight areas and dead space, image intensification devices for close range, thermal sights for camouflage, and smoke penetration for low light conditions. A mix of devices is best because several devices permit overlapping sectors and more coverage, and the capabilities of one device can compensate for limitations of another.

k. Target acquisition techniques used at night are similar to those used during the day. At night, whether using daylight optics or the unaided eye, a soldier does not look directly at an object but a few degrees off to the side. The side of the eye is more sensitive to dim light. When scanning with off-center vision, he moves his eyes in short, abrupt, irregular moves. At each likely target area, he pauses a few seconds to detect any motion.

l. Sounds and smells can aid in acquiring targets at night since they transmit better in the cooler, damper, night air. Running engines, vehicles, and soldiers moving through rubble-covered streets can be heard for great distances. Odors from diesel fuel, gasoline, cooking food, burning tobacco, after-shave lotion, and so on reveal enemy and friendly locations.

4. Flame Operations. Incendiary ammunition, special weapons, and the ease with which incendiary devices can be constructed from gasoline and other flammables make fire a true threat in built-up area operations. During defensive operations, firefighting should be a primary concern. The proper steps must be taken to reduce the risk of a fire that could make a chosen position indefensible.

a. Soldiers choose or create positions that do not have large openings. These positions provide as much built-in cover as possible to prevent penetration by incendiary ammunition. All unnecessary flammable materials are removed, including ammunition boxes, rugs, newspapers, curtains, and so on. The electricity and gas coming into the building must be shut off.

b. A building of concrete block construction, with concrete floors and a tin roof, is an ideal place for a position. However, most buildings have wooden floors or subfloors, wooden rafters, and wooden inner walls, which require improvement. Inner walls are removed and replaced with blankets to resemble walls from the outside. Sand is spread 2 inches deep on floors and in attics to retard fire.

c. All available firefighting gear is pre-positioned so it can be used during actual combat. For the individual soldier, such gear includes entrenching tools, helmets, sand, and blankets. These items are supplemented with fire extinguishers that are not in use.

d. Fire is so destructive that it can easily overwhelm personnel regardless of extraordinary precautions. Soldiers plan routes of withdrawal so that a priority of evacuation can be sent from fighting positions. This allows soldiers to exit through areas that are free from combustible material and provide cover from enemy direct fire.

e. The confined space and large amounts of combustible material in built-up areas can influence the enemy to use incendiary devices. Two major first-aid problems that are more urgent than in the open battlefield are: burns, and smoke and flame inhalation, which creates a lack of oxygen. These can easily occur in buildings and render the victim combat ineffective. Although there is little defense against flame inhalation and lack of oxygen, smoke inhalation can be greatly reduced by wearing the individual protective mask. Regardless of the fire hazard, defensive planning for combat in built-up areas must include aidmen. Aidmen must reach victims and their equipment, and must have extra supplies for the treatment of burns and inhalation injuries.

5. Employment of Snipers. The value of the sniper to a unit operating in a built-up area depends on several factors. These factors include the type of operation, the level of conflict, and the rules of engagement. Where ROE allow destruction, the snipers may not be needed since other weapons systems available to a mechanized force-have greater destructive effect. However, they can contribute to the fight. Where the ROE prohibit collateral damage, snipers may be the most valuable tool the commander has. (See FM 7-20; FM 71-2, C1; and TC 23-14 for more information.)

a. Sniper effectiveness depends in part on the terrain. Control is degraded by the characteristics of an urban area. To provide timely and effective support, the sniper must have a clear picture of the commander's concept of operation and intent.

b. Snipers should be positioned in buildings of masonry construction. These buildings should also offer long-range fields of fire and all-round observation. The sniper has an advantage because he does not have to move with, or be positioned with, lead elements. He may occupy a higher position to the rear or flanks and some distance away from the element he is supporting. By operating far from the other elements, a sniper avoids decisive engagement but remains close enough to kill distant targets that threaten the unit. Snipers should not be placed in obvious positions, such as church steeples and roof tops, since the enemy often observes these and targets them for destruction. Indirect fires can generally penetrate rooftops and cause casualties in top floors of buildings. Also snipers should not be positioned where there is heavy traffic; these areas invite enemy observation as well.

c. Snipers should operate throughout the area of operations, moving with and supporting the companies as necessary. Some teams may operate independent of other forces. They search for targets of opportunity, especially for enemy snipers. The team may occupy multiple positions. A single position may not afford adequate observation for the entire team without increasing the risk of detection by the enemy. Separate positions must maintain mutual support. Alternate and supplementary positions should also be established in urban areas.

d. Snipers may be assigned tasks such as the following:

(1) Killing enemy snipers (countersniper fire).

(2) Killing targets of opportunity. These targets may be prioritized by the commander. Types of targets might include enemy snipers, leaders, vehicle commanders, radio men, sappers, and machine gun crew.

(3) Denying enemy access to certain areas or avenues of approach (controlling key terrain).

(4) Providing fire support for barricades and other obstacles.

(5) Maintaining surveillance of flank and rear avenues of approach (screening).

(6) Supporting local counterattacks with precision fire.

NAVIGATION IN BUILT-UP AREAS

Built-up areas present a different set of challenges involving navigation. Deep in the city core, the normal terrain features depicted on maps may not apply - buildings become the major terrain features and units become tied to streets. Fighting in the city destroys buildings whose rubble blocks streets. Street and road signs are destroyed during the fighting if they are not removed by the defenders. Operations in subways and sewers present other unique challenges. However, maps and photographs are available to help the unit overcome these problems. The global positioning system (GPS) can provide navigation abilities in built-up areas.

1. Military Maps. The military city map is a topographical map of a city that is usually a 1:12,500 scale, delineating streets and showing street names, important buildings, and other urban elements. The scale of a city map can vary from 1:25,000 to 1:50,000, depending on the importance and size of the city, density of detail, and intelligence information.

a. Special maps, prepared by supporting topographic engineers, can assist units in navigating in built-up areas. These maps have been designed or modified to give information not covered on a standard map, which includes maps of road and bridge networks, railroads, built-up areas, and electric power fields. They can be used to supplement military city maps and topographical maps.

b. Once in the built-up area, soldiers use street intersections as reference points much as hills and streams in rural terrain. City maps supplement or replace topographic maps as the basis of navigation. These maps enable units moving in the built-up area to know where they are and to move to new locations even though streets have been blocked or a key building destroyed.

c. The old techniques of compass reading and pace counting can still be used, especially in a blacked-out city where street signs and buildings are not visible. The presence of steel and iron in the MOUT environment may cause inaccurate compass readings. Sewers must be navigated much the same way. Maps providing the basic layout of the sewer system are maintained by city sewer departments. This information includes directions the sewer lines run and distances between manhole covers. Along with basic compass and pace count techniques, such information enables a unit to move through the city sewers.

d. Operations in a built-up area adversely affect the performance of sophisticated electronic devices such as GPS and data distribution systems. These systems function the same as communications equipment - by line-of-sight. They cannot determine underground locations or positions within a building. These systems must be employed on the tops of buildings, in open areas, and down streets where obstacles will not affect line of sight readings.

e. City utility workers are assets to units fighting in built-up areas. They can provide maps of sewers and electrical fields, and information about the city. This is important especially with regard to the use of the sewers. Sewers can contain pockets of methane gas that are-highly toxic to humans. City sewer workers know the locations of these danger areas and can advise a unit on how to avoid them.

2. Global Positioning Systems. Most global positioning systems use a triangular technique using satellites to calculate their position. Preliminary tests have shown that GPS are not affected by small built-up areas, such as villages. However, large built-up areas with a mixture of tall and short buildings cause some degradation of most GPS. This affect may increase as the system is moved into an interior of a large building or taken into subterranean areas.

3. Aerial Photographs. Current aerial photographs are also excellent supplements to military city maps and can be substituted for a map. A topographic map or military city map could be obsolete if compiled many years ago. A recent aerial photograph shows changes that have taken place since the map was made. This could include destroyed buildings and streets that have been blocked by rubble as well as enemy defensive preparations. More information can be gained by using aerial photographs and maps together than using either one alone.

CAMOUFLAGE

To survive and win in combat in built-up areas, a unit must supplement cover and concealment with camouflage. To properly camouflage men, carriers, and equipment, soldiers must study the surrounding area and make positions look like the local terrain.

1. Application. Only the material needed for camouflaging a position should be used since excess material could reveal the position. Material must be obtained from a wide area. For example, if defending a cinder block building, do not strip the front, sides, or rear of the building to camouflage a position.

a. Buildings provide numerous concealed positions. Armored vehicles can often find isolated positions under archways or inside small industrial or commercial structures. Thick masonry, stone, or brick wall offer excellent protection from direct fire and provide concealed routes.

b. After camouflage is completed, the soldier inspects positions from the enemy's viewpoint. He makes routine checks to see if the camouflage remains natural looking and actually conceals the position. If it does not look natural, the soldier must rearrange or replace it.

c. Positions must be progressively camouflaged as they are prepared. Work should continue until all camouflage is complete. When the enemy has air superiority, work may be possible only at night. Shiny or light-colored objects that attract attention from the air must be hidden.

d. Shirts should be worn since exposed skin reflects light and attracts the enemy. Even dark skin reflects light because of its natural oils.

e. Camouflage face paint is issued in three standard, two-tone sticks. When issue-type face paint sticks are not available, burnt cork, charcoal, or lampblack can be used to tone down exposed skin. Mud may be used as a last resort since it dries and may peel off, leaving the skin exposed; it may also contain harmful bacteria.

2. Use of Shadows. Buildings in built-up areas throw sharp shadows, which can be used to conceal vehicles and equipment (Figure 3-18). Soldiers should avoid areas that are not in shadows. Vehicles may have to be moved periodically as shadows shift during the day. Emplacements inside buildings provide better concealment.

Figure 3-18. Use of shadows for concealment.

a. Soldiers should avoid the lighted areas around windows and loopholes. They will be better concealed if they fire from the shadowed interior of a room (Figure 3-19).

b. A lace curtain or piece of cheesecloth provides additional concealment to soldiers in the interior of rooms if curtains are common to the area. Interior lights are prohibited.

Figure 3-19. Concealment inside a building.

3. Color and Texture. Standard camouflage pattern painting of equipment is not as effective in built-up areas as a solid, dull, dark color hidden in shadows. Since repainting vehicles before entering a built-up area is not always practical, the lighter sand-colored patterns should be subdued with mud or dirt.

a. The need to break up the silhouette of helmets and individual equipment exists in built-up areas the same as it does elsewhere. However, burlap or canvas strips are a more effective camouflage than foliage (Figure 3-20). Predominant colors are normally browns, tans, and sometimes grays rather than greens, but each camouflage location should be evaluated.

Figure 3-20. Helmet camouflaged with burlap strips.

b. Weapons emplacements should use a wet blanket (Figure 3-21), canvas, or cloth to keep dust from rising when the weapon is fired.

Figure 3-21. Wet blanket used to keep dust down.

c. Command posts and logistical emplacements are easier to camouflage and better protected if located underground. Antennas can be moved to upper stories or to higher buildings based on remote capabilities. Field telephone wire should be laid in conduits, in sewers, or through buildings.

d. Soldiers should consider the background to ensure that they are not silhouetted or skylined, but rather blend into their surroundings. To defeat enemy urban camouflage, soldiers should be alert for common camouflage errors such as the following:

(1) Tracks or other evidence of activity.

(2) Shine or shadows.

(3) An unnatural color or texture.

(4) Muzzle flash, smoke, or dust.

(5) Unnatural sounds and smells.

(6) Movement.

e. Dummy positions can be used effectively to distract the enemy and make him reveal his position by firing.

f. Built-up areas afford cover, resources for camouflage, and locations for concealment. The following basic rules of cover, camouflage, and concealment should be adhered to:

(1) Use the terrain and alter camouflage habits to suit your surroundings.

(2) Employ deceptive camouflage of buildings.

(3) Continue to improve positions. Reinforce fighting positions with sandbags or other fragment- and blast-absorbent material.

(4) Maintain the natural look of the area.

(5) Keep positions hidden by clearing away minimal debris for fields of fire.

(6) Choose firing ports in inconspicuous spots when available.

NOTE:

Remember that a force that COVERS and CONCEALS itself has a significant advantage over a force that does not.

Proceed to Practice Exercise 3-1.

COMBAT SUPPORT

Combat support is fire support and other assistance provided to combat elements. It normally includes field artillery, air defense, aviation (less air cavalry), engineers, military police, communications, electronic warfare, and NBC.

1. Mortars. Mortars are the most responsive indirect fires available to battalion and company commanders. Their mission is to provide close and immediate fire support to the maneuver units. Mortars are well suited for combat in built-up areas because of their high rate of fire, steep angle of fall, and short minimum range. Battalion and company commanders must plan mortar support with the FSO as part of the total fire support system. (See FM 7-90 for detailed information on the tactical employment of mortars.)

a. Role of Mortar Units. The role of mortar units is to deliver suppressive fires to support maneuver, especially against dismounted infantry. Mortars can be used to obscure, neutralize, suppress, or illuminate during MOUT. Mortar fires inhibit enemy fires and movement, allowing friendly forces to maneuver to a position of advantage. Effectively integrating mortar fires with dismounted maneuver is key to successful combat in a built-up area at the rifle company and battalion level.

b. Position Selection. The selection of mortar positions depends on the size of buildings, the size of the urban area, and the mission. Also, rubble can be used to construct a parapet for firing positions.

(1) The use of existing structures (for example, garages, office buildings, or highway overpasses) for hide positions is recommended to afford maximum protection and minimize the camouflage effort. By proper use of mask, survivability can be enhanced. If the mortar has to fire in excess of 885 mils to clear a frontal mask, the enemy counterbattery threat is reduced. These principles can be used in both the offense and the defense.

(2) Mortars should not be mounted directly on concrete; however, sandbags may be used as a buffer. Sandbags should consist of two or three layers; be butted against a curb or wall; and extend at least one sandbag width beyond the baseplate.

(3) Mortars are usually not placed on top of buildings because lack of cover and mask makes them vulnerable. They should not be placed inside buildings with damaged roofs unless the structure's stability has been checked. Overpressure can injure personnel, and the shock on the floor can weaken or collapse the structure.

c. Communications. An increased use of wire, messenger, and visual signals will be required. However, wire should be the primary means of communication between the forward observers, fire support team, fire direction center, and mortars since elements are close to each other. Also, FM radio transmissions in

built-up areas are likely to be erratic. Structures reduce radio ranges; however, moving antennas to upper floors or roofs may improve communications and enhance operator survivability. Another technique that applies is the use of radio retransmissions. A practical solution is to use existing civilian systems to supplement the unit's capability.

d. Magnetic Interference. In an urban environment, all magnetic instruments are affected by surrounding structural steel, electrical cables, and automobiles. Minimum distance guidelines for the use of the M2 aiming circle (FM 23-90) will be difficult to apply. To overcome this problem, an azimuth is obtained to a distant aiming point. From this azimuth, the back azimuth of the direction of fire is subtracted. The difference is indexed on the red scale and the gun manipulated until the vertical cross hair of the sight is on the aiming point. Such features as the direction of a street may be used instead of a distant aiming point.

e. High-Explosive Ammunition. During MOUT, mortar HE fires are used more than any other type of indirect fire weapon. The most common and valuable use for mortars is often harassment and interdiction fires. One of their greatest contributions is interdicting supplies, evacuation efforts, and reinforcement in the enemy rear just behind his forward defensive positions. Although mortar fires are often targeted against roads and other open areas, the natural dispersion of indirect fires will result in many hits on buildings. Leaders must use care when planning mortar fires during MOUT to minimize collateral damage.

(1) High-explosive ammunition, especially the 120-mm projectile, gives good results when used on lightly built structures within cities. However, it does not perform well against reinforced concrete found in larger urban areas.

(2) When using HE ammunition in urban fighting, only point detonating fuzes should be used. The use of proximity fuzes should be avoided, because the nature of built-up areas causes proximity fuzes to function prematurely. Proximity fuzes, however, are useful in attacking targets such as OPs on tops of buildings.

(3) During both World War II and recent Middle East conflicts, light mortar HE fires have been used extensively during MOUT to deny the use of streets, parks, and plazas to enemy personnel.

f. Illumination. In the offense, illuminating rounds are planned to burst above the objective to put enemy troops in the light. If the illumination is behind the objective, the enemy troops would be in the shadows rather than in the light. In the defense, illumination is planned to burst behind friendly troops to put them in the shadows and place the enemy troops in the light. Buildings reduce the effectiveness of the illumination by creating shadows. Continuous illumination requires close coordination between the FO and FDC to produce the proper effect by bringing the illumination over the defensive positions as the enemy troops approach the buildings.

g. Special Considerations. When planning the use of mortars, commanders must consider the following:

(1) FOs should be positioned on tops of buildings so target acquisition and adjustments in fire can best be accomplished.

(2) Commanders must understand ammunition effects to correctly estimate the number of volleys needed for the specific target coverage. Also, the effects of using WP or LP may create unwanted smoke screens or limited visibility conditions that could interfere with the tactical plan.

(3) FOs must be able to determine dead space. Dead space is the area in which fires cannot reach the street level because of buildings. This area is a safe haven for the enemy. For mortars, the dead space is about one-half the height of the building.

(4) Mortar crews should plan to provide their own security.

(5) Commanders must give special consideration to where and when mortars are to displace while providing immediate indirect fires to support the overall tactical plan. Combat in built-up areas adversely affects the ability of mortars to displace because of rubbling and the close nature of MOUT.

2. Field Artillery. A field artillery battalion is normally assigned the tactical mission of direct support (DS) to a maneuver brigade. A battery may not be placed in DS of a battalion task force, but may be attached.

a. Appropriate fire support coordination measures should be carefully considered since fighting in built-up areas results in opposing forces fighting in close combat. When planning for fire support in a built-up area, the battalion commander in coordination with his FSO, considers the following.

(1) Target acquisition may be more difficult because of the increased cover and concealment afforded by the terrain. Ground observation is limited in built-up areas, therefore, FOs should be placed on tops of buildings. Adjusting fires is difficult since buildings block the view of adjusting rounds; therefore, the lateral method of adjustment should be used.

(2) Initial rounds are adjusted laterally until a round impacts on the street perpendicular to the FEBA. Airburst rounds are best for this adjustment. The adjustments must be made by sound. When rounds impact on the perpendicular street, they are adjusted for range. When the range is correct, a lateral shift is made onto the target and the gunner fires for effect.

(3) Special consideration must be given to shell and fuze combinations when effects of munitions are limited by buildings.

(a) Careful use of VT is required to avoid premature arming.

(b) Indirect fires may create unwanted rubble.

(c) The close proximity of enemy and friendly troops requires careful coordination.

(d) WP may create unwanted fires and smoke.

(e) Fuze delay should be used to penetrate fortifications .

(f) Illumination rounds can be effective; however, friendly positions should remain in shadows and enemy positions should be highlighted. Tall buildings may mask the effects illumination rounds.

(g) VT, TI, and ICM are effective for clearing enemy positions, observers, and antennas off rooftops.

(h) Swirling winds may degrade smoke operations.

(i) Family of scatterable mines (FASCAM) may be used to impede enemy movements. FASCAM effectiveness is reduced when delivered on a hard surface.

(4) Targeting is difficult in urban terrain because the enemy has many covered and concealed positions and movement lanes. The enemy may be on rooftops and in buildings, and may use sewer and subway systems. Aerial observers are extremely valuable for targeting because they can see deep to detect movements, positions on rooftops, and fortifications. Targets should be planned on rooftops to clear away enemy FOs as well as communications and radar equipment. Targets should also be planned on major roads, at road intersections, and on known or likely enemy fortifications. Employing artillery in the direct fire mode to destroy fortifications should be considered. Also, restrictive fire support coordination measures (such as a restrictive fire area or no-fire area) may be imposed to protect civilians and critical installations.

(5) The 155-mm and 8-inch self-propelled howitzers are effective in neutralizing concrete targets with direct fire. Concrete-piercing 155-mm and 8-inch rounds can penetrate 36 inches and 56 inches of concrete, respectively, at ranges up to 2,200 meters. These howitzers must be closely protected when used in the direct-fire mode since none of them have any significant protection for their crews. Restrictions may be placed on types of artillery ammunition used to reduce rubbling on avenues of movement that may be used by friendly forces.

(6) Forward observers must be able to determine where and how large the dead space is. Dead space is the area in which indirect fires cannot reach the street level because of buildings. This area is a safe haven for the enemy because he is protected from indirect fires. For low-angle artillery, the dead space is about five times the height of the building. For mortars and high-angle artillery, the dead space is about one-half the height of the building.

(7) Aerial observers are effective for seeing behind buildings immediately to the front of friendly forces. They are extremely helpful when using the ladder method of adjustment because they may actually see the adjusting rounds impact behind buildings. Aerial observers can also relay calls for fire when communications are degraded due to power lines or building mask.

(8) Radar can locate many artillery and mortar targets in an urban environment because of the high percentage of high-angle fires. If radars are sited too close behind tall buildings, some effectiveness will be lost.

b. The use of airburst fires is an effective means of clearing snipers from rooftops. HE shells with delay fuzes may be effective against enemy troops in the upper floors of buildings, but due to the overhead cover provided by the building, such shells have little effect on the enemy in the lower floors.

3. Naval Gunfire. When a unit is operating with gunfire support within range, naval gunfire can provide effective fire support. If naval gunfire is used, a supporting arms liaison team (SALT) of a US Marine air naval gunfire liaison company (ANGLICO) may be attached to the battalion. The SALT consists of one liaison section that operates at the battalion main CP. It also has two firepower control teams at the company level, providing ship-to-shore communications and coordination for naval gunfire support. The SALT collocates and coordinates all naval gunfire support with battalion FSE.

4. Tactical Air. A battalion may be supported by USAF, USN, USMC, or allied fighters and attack aircraft while fighting in built-up areas.

a. The employment of close air support (CAS) depends on the following.

(1) Shock and concussion. Heavy air bombardment provides tactical advantages to an attacker. The shock and concussion of the bombardment reduce the efficiency of defending troops and destroy defensive positions.

(2) Rubble and debris. The rubble and debris resulting from air attacks may increase the defender's cover while creating major obstacles to the movement of attacking forces.

(3) Proximity of friendly troops. The proximity of opposing forces to friendly troops may require the use of precision-guided munitions and may require the temporary disengagement of friendly forces in contact. The AC-130 is the air weapons platform of choice for precision MOUT as the proximity of friendly troops precludes other tactical air use.

(4) Indigenous civilians or key facilities. The use of air weapons may be restricted by the presence of civilians or the requirement to preserve key facilities within a city.

(5) Limited ground observation. Limited ground observation may require the use of airborne FAC.

b. CAS may be employed during defensive operations:

(1) To strike enemy attack formations and concentrations outside the built-up area.

(2) To provide precision-guided munitions support to counterattacks for recovering fallen friendly strongpoints.

5. Air Defense. Basic air defense doctrine does not change when units operate in urbanized terrain. The fundamental principles of mix, mass, mobility, and integration all apply to the employment of air defense assets.

a. The ground commander must consider the following when developing his defense plan.

(1) Enemy air targets, such as principal lines of communications, road and rail networks, and bridges, are often found in and around built-up areas.

(2) Good firing positions may be difficult to find and occupy for long-range air defense missile systems in the built-up areas. Therefore, the number of weapons the commander can employ may be limited.

(3) Movement between positions is normally restricted in built-up areas.

(4) Long-range systems can provide air defense cover from positions on or outside of the edge of the city.

(5) Radar masking and degraded communications reduce air defense warning time for all units. Air defense control measures must be adjusted to permit responsive air defense within this reduced warning environment.

b. Positioning of Vulcan weapons in built-up areas is often limited to more open areas without masking such as parks, fields, and rail yards. Towed Vulcans (separated from their prime movers) may be emplaced by helicopter onto rooftops in dense built-up areas to provide protection against air attacks from all directions. This should be accomplished only when justified by the expected length of occupation of the area and of the enemy air threat.

c. Stingers provide protection for battalions the same as in any operation. When employed within the built-up area, rooftops normally offer the best firing positions.

d. Heavy machine guns emplaced on rooftops can also provide additional air defense.

6. Army Aviation. Army aviation support of urban operations includes attack, observation, utility, and cargo helicopters for air movement or air assault operations, command and control, observation, reconnaissance, operations of sensory devices, attack, radio transmissions, and medical evacuation. When using Army aviation, the commander considers the enemy air situation, enemy air defenses, terrain in or adjacent to the city, and the availability of Army or Air Force suppression means. Missions for Army aviation during urban defensive operations include:

a. Long-range anti-armor fire.

b. Rapid insertion or relocation of personnel (anti-armor teams and reserves).

c. Rapid concentration of forces and fires.

d. Retrograde movement of friendly forces.

e. Combat service support operations.

f. Command and control.

g. Communications.

h. Intelligence gathering operations.

7. Helicopters. An advantage can be gained by air assaulting onto rooftops. Before a mission, an inspection should be made of rooftops to ensure that no obstacles exist, such as electrical wires, telephone poles, antennas, or enemy-emplaced mines and wire, that could damage helicopters or troops. In many modern cities, office buildings often have helipads on their roofs, which are ideal for landing helicopters. Other buildings, such as parking garages, are usually strong enough to support the weight of a helicopter. The delivery of troops onto a building can also be accomplished by rappelling from the helicopter or jumping out of the helicopter while it hovers just above the roof.

a. Small-Scale Assaults. Small units may have to be landed onto the rooftop of a key building. Success depends on minimum exposure and the suppression of all enemy positions that could fire on the helicopter. Depending on the construction of the roof, rappelling troops from the helicopter may be more of an advantage than landing them on the rooftop. The rappel is often more reliable and safer for the troops than a jump from a low hover. With practice, soldiers can accomplish a rappel insertion with a minimum of exposure.

b. Large-Scale Assaults. For large-scale air assaults, rooftop landings are not practical. Therefore, open spaces (parks, parking lots, sports arenas) within the built-up area must be used. Several spaces large enough for helicopter operations normally can be found within 2 kilometers of a city's center.

c. Air Movement of Troops and Supplies. In battle in a built-up area, heliborne troop movement may become a major requirement. Units engaged in house-to-house fighting normally suffer more casualties than units fighting in open terrain. The casualties must be evacuated and replaced quickly with new troops. At the same time, roads are likely to be crowded with resupply and evacuation vehicles, and also be blocked with craters or rubble. Helicopters provide a responsive means to move troops by flying nap-of-the-earth flight techniques down selected streets already secured and cleared of obstacles. Aircraft deliver the troops at the last covered position short of the fighting and then return without exposure to enemy direct fire. Similar flight techniques can be used for air movement of supplies and medical evacuation missions.

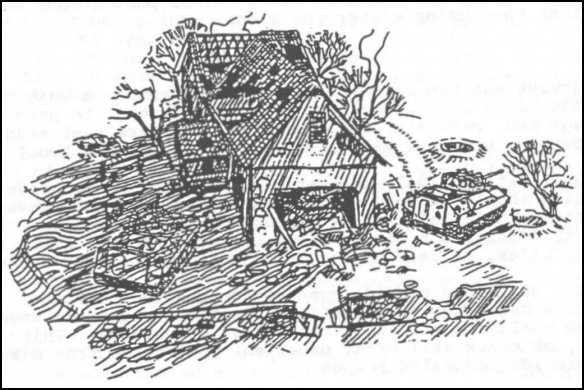

d. Air Assaults. Air assaults into enemy-held territory are extremely difficult (Figure 3-22). One technique is to fly nap-of-the-earth down a broad street or commercial ribbon while attack helicopters and door gunners from utility helicopters suppress buildings on either side of the street. Scheduled artillery preparations can be incorporated into the air assault plan through the H-hour sequence. Feints and demonstrations in the form of false insertions can confuse the enemy as to the real assault landings.

Figure 3-22. Air assault of a built-up area.

8. Engineers. The engineer terrain team supports the division commander and staff with specialized terrain analyses, products, and information for combat in built-up areas. During fighting in built-up areas, divisional engineers should be attached to the dispersed maneuver elements; for example, one engineer company to each committed brigade, one platoon to each battalion or battalion task force, and a squad to each company or company team. Most engineer manual-labor tasks, however, will have to be completed by infantry units, with reinforcing engineer heavy-equipment support and technical supervision.

a. Defensive Mission. Engineers may perform the following missions during the defense of a built-up area.

(1) Construct complex obstacle systems.

(2) Provide technical advice to maneuver commanders.

(3) Rubble buildings.

(4) Lay mines.

(5) Assist in the preparation of defensive strongpoints.

(6) Maintain counterattack, communications, and resupply routes.

(7) Enhance movement between buildings, catwalks, bridges, and so on.

(8) Fight as infantry, when needed.

b. Defense Against Armor. In defensive situations, when opposed by an armor-heavy enemy, priority should be given to the construction of anti-armor obstacles throughout the built-up area. Use of local materials, where possible, makes obstacle construction easier and reduces logistics requirements. Streets should be barricaded in front of defensive positions at the effective range of anti-armor weapons. These weapons are used to increase the destruction by anti-armor fires, to separate dismounted enemy infantry from their supporting tanks, and to assist in the delay and destruction of the attacker. Anti-armor mines with anti-handling devices, integrated with antipersonnel mines in and around obstacles and covered by fires, help stop an enemy attack.

9. Military Police. Military police (MP) operations play a significant role by assisting the tactical commander in meeting the challenges with combat in built-up areas. Through their four battlefield missions (battlefield circulation control, area security, EPW operations, and law and order) MP provide a wide range of diverse support in urban terrain. MP operations require continuous coordination-with host nation civilian police to maintain control of the civilian population and to enforce law and order.

a. MP units take measures to support area damage control operations that are frequently found in built-up areas. With the increased possibility of rubbling, MP units report, block off affected areas, and reroute movement to alternate road networks.

b. MP units also secure critical activities, such as communications centers and water and electrical supply sources. They are responsible for securing critical cells within the corps and Theater Army Area Command (TAACOM) main CPs, which often use existing "hardstand" structures located in built-up areas.

c. MP units are tasked with EPW operations and collect them as far forward as possible. They operate collecting points and holding areas to briefly retain EPWs and civilian internees (CI). EPW operations are of great importance in built-up areas because the rate of capture can be higher than normal.

d. Commanders must realize that MP support may not be available and that infantry soldiers may have to assume certain MP missions. The following are some of those missions:

(1) Route reconnaissance, selection of routes and alternate routes, convoy escort, and security of lines of communication.

(2) Control of roads, waterways, and railroad terminals, which are critical chokepoints in the main supply routes.

(3) Security of critical sites and facilities to include communication centers, government buildings, water and electrical supply sources, C4 nodes, nuclear or chemical delivery means and storage facilities, and other mission essential areas.

(4) Refugee control in close cooperation with host nation civil authorities. (FM 90-10-1, Chapter 7 for more information.)

(5) Collection and escort of EPWs.

10. Communications. Buildings and electrical power lines reduce the range of FM radios. To overcome this problem, battalions set up retransmission stations or radio relays, which are most effective when placed in high areas. Antennas should be camouflaged by placing them near tall structures. Remoting radio sets or placing antennas on rooftops can also solve the range problem.

a. Wire. Wire is a more secure and effective means of communications in built-up areas. Wire should be laid overhead on existing poles or underground to prevent vehicles from cutting them.

b. Messengers and Visual Signals. Messengers and visual signals can also be used in built-up areas. Messengers must plan routes that avoid pockets of resistance. Routes and time schedules should be varied to avoid establishing a pattern. Visual signals must be planned so they can be seen from the buildings.

c. Sound. Sound signals are normally not effective in built-up areas due to too much surrounding noise.

d. Existing Systems. If existing civil or military communications facilities can be captured intact, they can also be used by the infantry battalion. A civilian phone system, for instance, can provide a reliable, secure means of communication if codes and authentication tables are used. Other civilian media can also be used to broadcast messages to the public.

(1) Evacuation notices, evacuation routes, and other emergency notices designed to warn or advise the civilian population must be coordinated through the civil affairs officer. Such notices should be issued by the local civil government through printed or electronic news media.

(2) Use of news media channels in the immediate area of combat operations for other than emergency communications must also be coordinated through the civil affairs officer. A record copy of such communications will be sent to the first public affairs office in the chain of command.

EMPLOYMENT AND EFFECTS OF WEAPONS

This section supplements the technical manuals and field manuals that describe weapons capabilities and effects against generic targets. It focuses on specific employment considerations pertaining to combat in built-up areas, and it addresses both organic infantry weapons and combat support weapons.

1. Effectiveness of Weapons and Demolitions. The characteristics and nature of combat in built-up areas affect the results and employment of weapons. Leaders at all levels must consider the following factors in various combinations when choosing their weapons.

a. Hard, smooth, flat surfaces are characteristic of urban targets. Rarely do rounds impact perpendicular to these flat surfaces but at some angle of obliquity. This reduces the effect of a round and increases the threat of ricochets. The tendency of rounds to strike glancing blows against hard surfaces means that up to 25 percent of impact-fuzed explosive rounds may not detonate when fired onto rubbled areas.

b. Engagement ranges are close. Studies and historical analyses have shown that only 5 percent of all targets are more than 100 meters away. About 90 percent of all targets are located 50 meters or less from the identifying soldier. Few personnel targets will be visible beyond 50 meters and usually occur at 35 meters or less. Minimum arming ranges and troop safety from backblast or fragmentation effects must be considered.

c. Engagement times are short. Enemy personnel present only fleeting targets. Enemy-held buildings or structures are normally covered by fire and often cannot be engaged with deliberate, well-aimed shots.

d. Depression and elevation limits for some weapons create dead space. Tall buildings form deep canyons that are often safe from indirect fires. Some weapons can fire rounds to ricochet behind cover and inflict casualties. Target engagement from oblique angles, both horizontal and vertical, demands superior marksmanship skills.

e. Smoke from burning buildings, dust from explosions, shadows from tall buildings, and the lack of light penetrating inner rooms all combine to reduce visibility and to increase a sense of isolation. Added to this is the masking of fires caused by rubble and man-made structures. Targets, even those at close range, tend to be indistinct.

f. Urban fighting often becomes confused melees with several small units attacking on converging axes. The risks from friendly fires, ricochets, and fratracide must be considered during the planning phase of operations and control measures continually adjusted to lower these risks. Soldiers and leaders must maintain a sense of situational awareness and clearly mark their progress in accordance with (IAW) unit SOP to avoid fratricide.

g. Both the firer and target may be inside or outside buildings, or they may both be inside the same or separate buildings. The enclosed nature of combat in built-up areas means that the weapon's effect, such as muzzle blast and backblast, must be considered as well as the round's impact on the target.

h. Usually the man-made structure must be attacked before enemy personnel inside are attacked. Therefore, weapons and demolitions can be chosen for employment based on their effects against masonry and concrete rather than against enemy personnel.

i. Modern engineering and design improvements mean that most large buildings constructed since World War II are resilient to the blast effects of bomb and artillery attack. Even though modern buildings may burn easily, they often retain their structural integrity and remain standing. Once high-rise buildings burn out, they are still useful to the military and are almost impossible to damage further. A large structure can take 24 to 48 hours to burn out and get cool enough for soldiers to enter.

j. The most common worldwide building type is the 12- to 24-inch brick building. Table 3-1 lists the frequency of occurrence of building types worldwide.

Table 3-1. Types of buildings and frequency of occurrence.

2. M16 Rifle and M249 Squad Automatic Weapon/Machine Gun. The M16A1/M16A2 rifle is the most common weapon fired in built-up areas. The M16A1/M16A2 rifle and the M249 are used to kill enemy personnel, to suppress enemy fire and observation, and to penetrate light cover. Leaders can use 5.56-mm tracer fire to designate targets for other weapons.

a. Employment. Close combat is the predominant characteristic of urban engagements. Riflemen must be able to hit small, fleeting targets from bunker apertures, windows, and loopholes. This requires pinpoint accuracy with weapons fired in the semi-automatic mode. Killing an enemy through an 8-inch loophole at a range of 50 meters is a challenge, but one that may be common in combat in built-up areas.

(1) When fighting inside buildings, three-round bursts or rapid semiautomatic fire should be used. To suppress defenders while entering a room, a series of rapid three-round bursts should be fired at all identified targets and likely enemy positions. This is more effective than long bursts or spraying the room with automatic fire. Soldiers should fire from an underarm or shoulder position; not from the hip.

(2) When targets reveal themselves in buildings, the most effective engagement is the quick-fire technique with the weapon up and both eyes open. (See FM 23-9 for more detailed information on this technique.) Accurate quick fire not only kills enemy soldiers but also gives the attacker fire superiority.

(3) Within built-up areas, burning debris, reduced ambient light, strong shadow patterns of varying density, and smoke all limit the effect of night vision and sighting devices. The use of aiming stakes in the defense and of the pointing technique in the offense, both using three-round bursts, are night firing skills required of all infantrymen. The individual laser aiming light can sometimes be used effectively with night vision goggles. Any soldier using NVG should be teamed with at least one soldier not wearing them.

b. Weapon Penetration. The penetration that can be achieved with a 5.56-mm round depends on the range to the target and the type of material being fired against. The M16A2 and M249 achieve greater penetration than the older M16A1, but only at longer ranges. At close range, both weapons perform the same. Single 5.56-mm rounds are not effective against structural materials (as opposed to partitions) when fired at close range - the closer the range, the less the penetration.

(1) For the 5.56-mm round, maximum penetration occurs at 200 meters. At ranges less than 25 meters, penetration is greatly reduced. At 10 meters, penetration by the M16 round is poor due to the tremendous stress placed on this high-speed round, which causes it to yaw upon striking a target. Stress causes the projectile to break up, and the resulting fragments are often too small to penetrate.

(2) Even with reduced penetration at short ranges, interior walls made of thin wood paneling, sheetrock, or plaster are no protection against 5.56-mm rounds. Common office furniture such as desks and chairs cannot stop these rounds, but a layer of books 18 to 24 inches thick can.