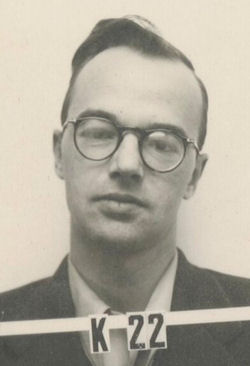

Klaus Fuchs - 1941 1949

German by birth, British by naturalization, Communist by conviction, Klaus Fuchs was a fearless Nazi resister, a brilliant scientist, and an infamous spy. Fuchs was, by far, the most damaging spy of wartime Los Alamos. Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (1911-1988) was a German-born atomic scientist who emigrated to Great Britain in the late 1930s. He worked on the joint U.S./British effort to build the atomic bomb. Fuchs position with regard to nuclear research in England was comparable to that of J. Robert Oppenheimer in the United States. A key factor in the Soviet Union’s ability to make progress on atomic energy was the information being provided by Klaus Emil Fuchs. He put an end to America's nuclear hegemony and single-handedly heated up the Cold War.

German by birth, British by naturalization, Communist by conviction, Klaus Fuchs was a fearless Nazi resister, a brilliant scientist, and an infamous spy. Fuchs was, by far, the most damaging spy of wartime Los Alamos. Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (1911-1988) was a German-born atomic scientist who emigrated to Great Britain in the late 1930s. He worked on the joint U.S./British effort to build the atomic bomb. Fuchs position with regard to nuclear research in England was comparable to that of J. Robert Oppenheimer in the United States. A key factor in the Soviet Union’s ability to make progress on atomic energy was the information being provided by Klaus Emil Fuchs. He put an end to America's nuclear hegemony and single-handedly heated up the Cold War.

Although Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (1911-1988) was a very talented theoretical physicist and was responsible for many significant theoretical calculations relating to nuclear and hydrogen weapons at the Los Alamos Laboratory, it was not science for which he is most remembered during and after the Manhattan Project. It was espionage. Following an FBI and British investigation, Fuchs was convicted of espionage in Great Britain for supplying atomic secrets to the Soviet Union. The Fuchs file is tied closely to that of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, two U.S. citizens who were convicted in 1950 of passing atomic secrets to the USSR.

He was born in 1911 in Rüsselsheim, Germany, to a Lutheran minister with socialist political leanings. Fuchs had attended the University of Leipzig where he was involved in student politics. In the early 1930s, he joined the Communist Party and became active politically in the struggle against the incipient Nazi Party. The young Fuchs and his idealistic family paid a heavy price for their political convictions in the face of Nazism’s rise. Fuchs’s background as a communist on the run from Nazi authorities in the early 1930s included experiences he’d draw upon later to operate successfully as a Soviet spy in the West. When the Nazis took power in 1933, Fuchs narrowly avoided arrest and fled first to Paris and then to Bristol, England. Continuing his studies in physics, Fuchs completed his Ph.D. in physics at the University of Bristol in 1937 and Doctor of Science from the University of Edinburgh. He was soon thereafter recruited by fellow-German émigré (and Robert Oppenheimer's thesis advisor) Max Born at Edinburgh.

In May 1940, as a German national, he was interned by the British government as an "enemy alien" on the Isle of Man and in Canada. The internment experience enhanced Fuchs’s Soviet connections, hardened his support for communism, and allowed him to further discipline his emotions in order to serve “the cause.” Following a brief period of internment in a Canadian Army camp, he was permitted to return to Edinburgh. In early 1941, British physicist and refugee from Nazi Germany Rudolf Peierls invited him to the University of Birmingham and took him in as a lodger. Peierls, a key figure on the MAUD Committee heading up atomic bomb research in Britain, soon asked him to work on Tube Alloys, the British atom bomb project, which Fuchs did in May 1941.

When it first appeared that scientists could produce the atomic bomb, the three countries then foremost in atomic research, Canada, England, and the United States, reached an agreement to pool the acquired knowledge of atomic explosives. It was agreed that because of facilities and "security," future experiments should be carried on in the United States. Dr. Klaus Fuchs, as the leading British atomic expert, was one of the individuals selected to represent Great Britain in this research. One of the mysteries in the selection of Fuchs was the failure of British authorities to notify the United States of all facts in their possession concerning the background of Dr. Fuchs. It was learned that as early as 1941 the British Government knew that the German Gestapo had named Klaus Fuchs as a German Communist. Even though the British had no way at that time of verifying the accuracy of the Gestapo charges, it is difficult to understand why there was no notification of this at the time Fuchs was permitted to enter this country.

Not long after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Fuchs, traveled to London, contacted a Soviet official, and volunteered his services as a spy. "I had complete confidence in Russian policy," Fuchs later noted in his confession, "and I believed that the Western Allies deliberately allowed Russia and Germany to fight each other to the death. I had therefore no hesitation in giving all the information I had." For the next two years, Fuchs met a total of six times with a Soviet handler and passed along information dealing mainly with gaseous diffusion. In early December 1943, Fuchs arrived in the United States as a member of the British contingent of scientists, including Peierls, assigned to assist on the Manhattan Project. Initially, he and Peierls worked on gaseous diffusion at Columbia University in New York. Fuchs was soon transferring information on the project to Soviet agents in New York.

As part of the British Mission, Peierls and Fuchs moved to Columbia University in August 1944, to work on gaseous diffusion with the Manhattan Project, and then to the secret Los Alamos laboratory. There, Fuchs joined the Theoretical Physics Division, headed by Hans Bethe. He was present at Trinity, and Bethe considered Fuchs, “one of the most valuable men in my division” and “one of the best theoretical physicists we had.” His report on blast waves is still a classic. In Los Alamos he was known as a quiet man and a good dancer, hiker, and babysitter. He was a close friend of Richard Feynman, who borrowed his car to go to Albuquerque when Feynman’s wife was his dying.

Fuchs continued passing valuable, accurate nuclear information to the Soviets, meeting his courier in Santa Fe for drop-offs. Klaus Fuchs was working at Los Alamos when he delivered the plans for Fat Man, the plutonium bomb dropped on Nagasaki, to the Soviets. He had also worked for a short time at Oak Ridge before going to Los Alamos. There is no record of any information being passed while he was in Oak Ridge.

British authorities deserve a significant portion of the blame for Fuchs’s espionage: first, in their harsh treatment of Fuchs as an enemy alien at the start of WWII; second, in their willful ignorance of Fuchs’s known communist identity, which allowed the UK to exploit his scientific brilliance; finally, in their decision to withhold these security concerns from US officials when Fuchs was assigned to the Manhattan Project, thus enabling his most lucrative espionage collection. MI5 ignored the security threat Fuchs posed in order to ensure the UK could exploit his abilities. That MI5 then hid this information from the United States on Fuchs’s transfer to the Manhattan Project. The UK played “Russian roulette” with Fuchs and “failed to tell the Americans about the bullet in the chamber.”

Soviet intelligence lost contact with him in early 1944 but eventually found out that Fuchs had been reassigned to the bomb research and development laboratory at Los Alamos as part of the newly-arrived contingent of British scientists. Fuchs worked in the Theoretical Division at Los Alamos, and from there he passed to his Soviet handlers detailed information regarding atomic weapons design.

In June 1944, Hans Bethe, head of the Theoretical Division (T Division) at Los Alamos, began looking for someone to replace Edward Teller, who had been in charge of the division's implosion group. Aware the Peierls was in New York, Bethe requested that Peierls be transferred to Los Alamos to head up implosion studies. Peierls agreed provide he could bring two assistants, one of whom was Fuchs. Arriving at Los Alamos August 14, 1944, Fuchs worked on problems relating to design of the implosion bomb. Bethe would later describe Fuchs as "one of the most valuable men in my division."

In February 1945, Fuchs, according to his confession, began to pass along central information regarding the need for an implosion design for plutonium weapons, the critical mass for such an assembly, and design concepts. In June 1945, just before Trinity, he passed along a sketch of the bomb, providing its components and dimensions, and described the design in great detail. "When combined with information from other sources," the British Secret Service, MI5, notes, "this helped the Russians to make rapid progress in developing what was effectively a copy of the American atomic bomb design."

Soviet intelligence faced challenges in handling this unique asset. Intelligence professionals will appreciate depictions of the intellectual Fuchs critiquing the lax tradecraft of his Soviet handlers, the difficulties these handlers faced in attempting to control an ideological asset who refused to accept money, and the anxiety of an intelligence service scrambling to locate the prized asset after he disappears for months at a time.

After the war, Fuchs stayed on at Los Alamos. In April 1946, he participated in a three-day secret conference on the hydrogen bomb (the Super). The conference reviewed progress made during the war, explored the path for future development, and concluded that it was likely that the Super could be constructed and that it would work. When it became known that Klaus Fuchs had given nuclear secrets from the United States design to the Soviets, fear grew that he may have provided them the design work that had been done on the thermonuclear weapon.

Fuchs possessed and was presumed to have transmitted to the Russians a full understanding of the Los Alamos thermonuclear weapon feasibility report of April 1946. This report contained all the essential ideas which led to the Greenhouse George shot on 08 May 1951. Radiation compression of DT to produce fusion energy was demonstrated in the Greenhouse George Cylinder test. The George shot in turn demonstrated the principle which greatly increased the probability of a practical and economical thermonuclear weapon and thus precipitated the current American redirected development program.

The idea of making a fusion (hydrogen) bomb and the physics involved in it were in a design proposed for one by the unlikely collaborators John von Neumann and Klaus Fuchs in a patent application they filed at Los Alamos in May 1946, which Fuchs passed on to the Russians in March 1948, and which with substantial modifications was tested in the Greenhouse George shot on the island of Eberiru on the Eniwetok atoll in the South Pacific on May 8, 1951. This test showed that the fusion of deuterium and tritium nuclei could be ignited, but that the ignition would not propagate because the heat produced was rapidly radiated away.

The Russians freely acknowledged that Fuchs gave them the fission bomb, but they have insisted that no one gave them the fusion bomb, which grew out of design involving a fission bomb surrounded by alternating layers of fusion and fission fuels, and which they tested on November 22, 1955. Part of the irony of this story is that neither the American nor the Russian hydrogen-bomb programs made any use of the brilliant design that von Neumann and Fuchs had conceived as early as 1946, which could have changed the entire course of development of both programs.

Information on the Super passed on by Fuchs helped spur the Soviet's thermonuclear program, but there is some debate as to the usefulness of the information itself. Bethe in May 1952 prepared a brief classified history of the U.S. thermonuclear program that considered if "the Russians may have been able to arrive at a usable thermonuclear weapon by straightforward development from the information they received from Fuchs in 1946." He concluded that subsequent developments had shown that "every important point of the 1946 thermonuclear program had been wrong. If the Russians started a thermonuclear program on the basis of the information received from Fuchs, it must have led to the same failure." Ironically, revelations of Fuchs's betrayal of American nuclear secrets helped accelerate and expand the U.S. thermonuclear program. Four days after Fuchs confessed to treason, President Harry Truman directed the Atomic Energy Commission to proceed with the development of the hydrogen bomb.

In the summer of 1946, Fuchs left Los Alamos and returned to Britain where he was offered a post working on the development of nuclear energy at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell. Fuchs had few regrets about betraying the UK or enabling Stalinism, but in the latter stages of his spying career, Fuchs withheld sensitive information from Soviet intelligence because of “questions” he had about Stalin. Fuchs abandoned the espionage relationship in the late 1940s. Considering that Stalin wanted a hydrogen bomb and Fuchs might have helped in that effort, and possibly he had second thoughts about whether working for Stalin was leading to the “betterment of mankind”.

He continued to pass secret information to the Soviet Union intermittently until he was finally caught, largely due to VENONA. On December 21, 1949, a British intelligence officer informed the physicist that they suspected him of passing classified information to the Soviet Union. Fuchs was arrested and, in January 1950, confessed. He was convicted of espionage and given a sentence of 14 years. His trial lasted only an hour and a half. It was done quietly and without exposing any information about Great Britain’s atomic weapons program being worked at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell. At the time of his arrest Fuchs was an assistant director at Harwell! Yet, he was known to be a spy. However, the method used to trap him was the secret “Venona Intercepts” and could not be exposed as the source of the information. He was sentenced to 14 years in prison, the maximum allowed for the stated violation.

He was released in 1959, after having served only nine years, and shortly thereafter moved to East Germany to resume his physics career, where he was a prominent physicist and honored scientific leader. Fuchs spent the rest of his life being monitored, mistrusted, and marginalized in East Germany. Fuchs remained an ardent communist and received numerous honors from his new home, including the Order of Karl Marx in 1979. Fuchs died on January 28, 1988.

Stanislaw Ulam and C.J. Everett had shown that Edward Teller's Classical Super could not work. At the end of December 1950, Ulam had conceived the idea of super compression, using the energy of a fission bomb to compress the fusion fuel to such a high density that it would be opaque to the radiation produced. Once Teller understood this, he invented a greatly improved, new method of compression using radiation, which then became the heart of the Ulam-Teller bomb design.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|