Go to report table of contents

5.0 Access Management

5.1 Overviewgo to top of the page

5.1.1 Access Management Parameters5.2 Tools/Techniques

5.1.2 Challenges in the Transit Environment

5.1.3 Access Management as Part of an Enterprise-wide Strategy

5.1.4 Access Management as Part of a Comprehensive Security Plan

5.1.5 Access Management Concepts

5.1.5.1 Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED)5.1.6 Implementation Challenges

5.1.5.2 Access Control

5.1.5.3 Intrusion Detection and Surveillance

5.1.5.4 Layered Security

5.1.5.5 Systems Integration

5.2.1 Policies and Procedures5.3 Sample Access Management Guidelines

5.2.2 Perimeter Protection and Barriers

5.2.3 Entry-Point Screening

5.2.4 Credentials and Credentialing

5.2.4.1 Credentials5.2.5 Surveillance Systems

5.2.4.2 Credentialing

5.2.6 Intrusion Detection

5.2.7 Security Personnel

5.2.8 Communication and Information Processing Systems

5.2.9 Lighting

5.3.1 Fencing and Gates

5.3.1.1 Perimeter Fences5.3.2 Security Lighting

5.3.1.2 Clear Zones

5.3.1.3 Fence Fabric

5.3.1.4 Posts and Hardware

5.3.1.5 Openings

5.3.1.6 Gates

5.3.2.1 Perimeter Lighting5.3.3 Admission Control

5.3.2.2 Entry, Guardhouse, and Parking Lot Lighting

5.3.2.3 Types of Lighting

5.3.3.1 Facility Employees, Contractors, and Visitors5.3.4 Vehicle Access Control and Parking

5.3.3.2 Pick-Ups and Deliveries

5.3.4.1 Vehicle Inspection5.3.5 Vehicle Barriers

5.3.4.2 Facility Parking/Traffic Control

5.3.4.3 Adjacent Parking

5.3.4.4 Parking Registration / Vehicular Identification Systems

5.3.4.5 Towing of Unauthorized Vehicles

5.3.4.6 Vehicle Access Points

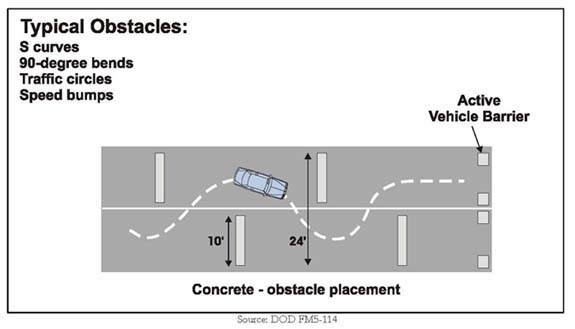

5.3.4.7 High-Speed Vehicle Approaches

5.3.4.8 Drive-Up / Drop Off Locations

5.3.4.9 Electronic Vehicle Access Control Systems

5.3.5.1 Barrier Use5.3.6 Critical and Restricted Area Access

5.3.5.2 Applications in a Transit Environment

5.3.5.3 Barrier Types

5.3.5.4 Barrier Selection and Implementation

5.3.6.1 Critical Operating Areas5.3.7 Windows

5.3.6.2 Hazardous Areas and Security Areas

5.3.7.1 Construction5.3.8 Wall Safeguards

5.3.7.2 Steel Bars and Grills

5.3.7.3 Glass Brick

5.3.7.4 Glass and Steel Framework

5.3.7.5 Security Glazing

5.3.8.1 Extending Interior Wall Construction to Ceiling or Roof Deck5.3.9 Miscellaneous Openings

5.3.8.2 Reinforced Wall

5.3.8.3 Intrusion-Detection Sensors

5.3.9.1 Fire Escapes5.3.10 Personnel Security

5.3.9.2 Manholes

5.3.9.3 Accessible Steel Grates and Doors

5.3.9.4 Sewers and Storm Drains

5.3.9.5 Rooftop Access Points

5.3.9.6 Air Intakes

5.3.10.1 Pre-Employment Screening5.3.11 Key Control

5.3.10.2 Levels of Screening

5.3.11.1 Control of Locks and Keys

5.3.11.2 Key Control Official

5.3.11.3 Records Requirements

5.3.11.4 Issue and Control Procedures

5.3.11.5 Lost and Unaccounted-for Keys and Electronic Access Cards

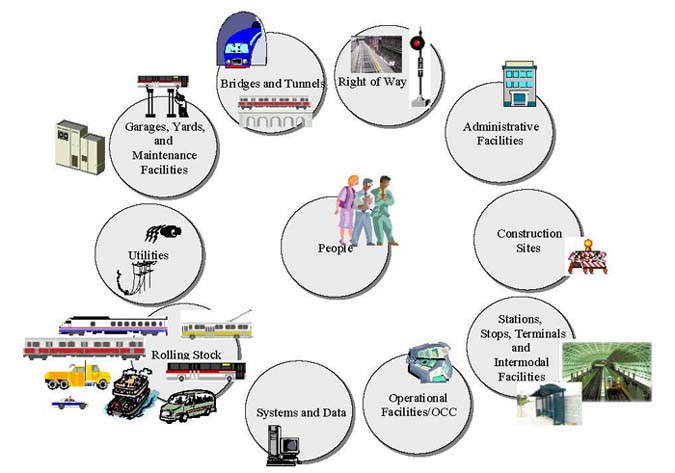

Figure 5-1 Transit System Assets

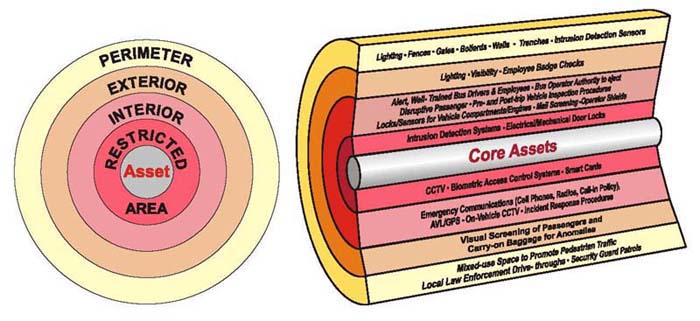

Figure 5-2 Layers of Security

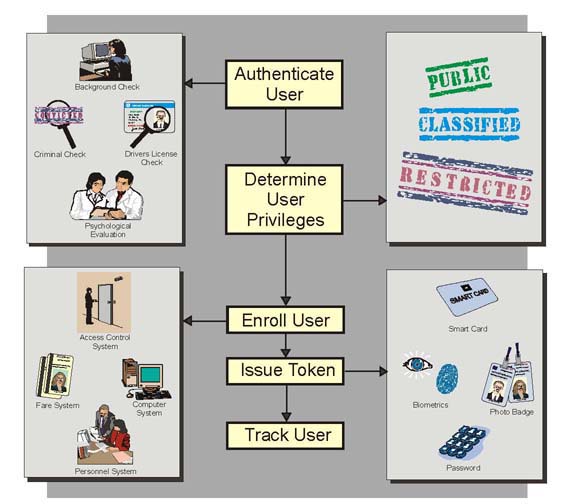

Figure 5-3. Access Management Component Integration

Figure 5-4. Entry Control Techniques

Figure 5-5. Credentialing and Access Control

Figure 5-6. Speed Reduction Approach

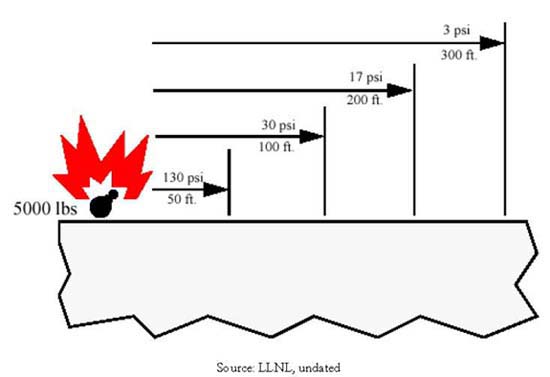

Figure 5-7. Blast Overpressures as a Function of Distance

Table 5 1. llluminance Specificationgo to top of the page

Table 5 2. Vehicle Barrier Usage

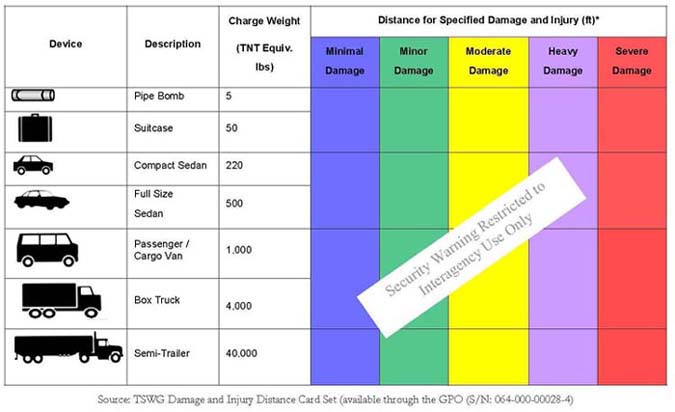

Table 5 3. Blast Damage

Table 5 4. Blast Charge and Damage Distance

Table 5 5. Sample Pre-Employment Background Screening Matrix

How is this chapter useful? For transit managers and security staff it is a resource for

|

Access management is a set of policies, plans, procedures, personnel, and physical components that provide control and awareness of assets and activities in and around facilities and restricted areas.

This chapter provides:

- An overview of access management,

- Tools and techniques for transit agencies to use in developing an effective access management strategy, and

- Sample guidelines for various access management security measures to help transit facility operators manage risks to their facilities and other assets.

Note that details on the design and strategies for access management systems are beyond the scope of this chapter. Refer to Chapter 6: Infrastructure, for a description of design-related security measures for stationary assets in a system, such as buildings, tunnels, wayside easement, and rail lines.

5.1 Overview

This section defines the parameters of access management, the challenges of incorporating access management into the transit environment, using access management as part of a planning strategy and security plan, the security concepts behind access management, and agency challenges when implementing access management systems.

5.1.1 Access Management Parameters

Access management controls who should be permitted access to facilities and restricted areas; where they can access (e.g., garage or rail yard facilities, vehicles, utility areas within stations or terminals); and when they can access these areas (e.g., certain days of the week or shifts). In addition to controlling passage in and out of facilities or areas, determining who belongs and who does not, access management includes the ability to observe and track movement in and out of controlled areas. Agencies grant access for various combinations of persons and assets, depending on the needs and restrictions established by each agency.

| What is Access Management? Policies, procedures, and physical components controlling passage in and out of facilities or areas, determining who belongs and who does not, and tracking movement in and out of controlled areas. |

Basic principles of access management include:

- Limiting the number of access points

- Identifying and dedicating secure areas

- Providing transition areas between secure and non-secure areas

- Minimizing interference with the movement of passengers and system operations

- Not interfering with fire protection and life safety systems

- Conforming to Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements

- Layering of security systems

- Using protective measures addressing all threat phases-deterrence, detection, defense, mitigation, response and recovery

- Providing an audit trail and/or transaction reporting capability

In developing an access management plan, agencies should consider identifying their assets and areas of their property/facilities that should be controlled. They can then make decisions about who will be given access to those assets and areas. From there, they can decide how different access management tools-such as intrusion detection and surveillance-can work together as a part of an integrated security system.

5.1.2 Challenges in the Transit Environment

| Access Management and the Transit Environment Access management controls and limits access to areas. Public transit requires unrestricted public access to much of the system. |

The objectives of access management and the mission of transit agencies are not always compatible with each other. The purpose of access management is to control and limit access, while public transit requires unrestricted public access to much of the system. In addition, transit systems serve mobile populations and contain mobile assets that are difficult to monitor and to secure.

Transit systems must accommodate thousands of customers daily-24 hours a day/seven days a week in some facilities. Customers using transit systems may pass near restricted areas such as tunnels, control rooms, utility rooms, power supplies, or hazardous-material storage areas. This presents a unique challenge for transit agencies; implementing access control systems that provide easy access to public areas of facilities, at the same time as limiting access to non-public areas to authorized personnel.

Transit agencies are constantly faced with the challenge of managing risks to diverse assets throughout the system. Access management strategies and systems for transit environments must work in a wide variety of settings and be effective in protecting diverse asset types (see Figure 5 1.).

|

Figure 5-1. Transit System Assets |

Each asset has its own level of risk-attractiveness as a target, vulnerabilities, accessibility, and criticality to the system. However, transit agency managers should consider prioritizing risks through threat and vulnerability assessments and select sets of countermeasures that provide the best overall risk reduction for the system as a whole. Since funding for security efforts is limited, agents must strive to ensure that protective security measures for each asset are equal to the threats and vulnerabilities of that particular asset and the potential consequences of an attack.

5.1.3 Access Management as Part of an Enterprise-wide Strategy

Access management-and security in general-is one concern within the broader operating environment of a transit agency. Agencies should consider balancing the desire for security against other objectives, such as operational efficiency, budgetary limitations, and passenger convenience. Access management strategies can be integrated into agency-wide planning efforts to ensure compatibility with other, non-security goals.

An agency's staff should consider ways in which access management systems can provide information that is useful to operational systems already in place. For example, agencies may integrate access management systems with a personnel system to track the presence of employees at restricted facilities. Security is the responsibility of all transit department staff; operational procedures and resources can be used to promote effective access management.

5.1.4 Access Management as Part of a Comprehensive Security Plan

A transit agency's access management efforts are part of a larger, comprehensive security plan that reflects an accurate assessment of critical assets and potential threats and vulnerabilities, and establishes a methodology for addressing them. The goal is to protect the agency's assets. In addition, because many access management tools have multiple security roles, access management efforts can be tightly woven into an overall security strategy.

Agencies should consider preparing and implementing access management strategies that are consistent with their comprehensive security plan. The TVA can be used to help determine which access management strategies to implement.

For guidance on preparing a security plan, refer to The Public Transportation System Security and Emergency Preparedness Planning Guide 1 [FTA, 2003].

1http://transit-safety.volpe.dot.gov/Publications/security/PlanningGuide.pdf

5.1.5 Access Management Concepts

An effective access management strategy draws on several broad security concepts: CPTED, access control, intrusion detection/surveillance, layered security, and systems integration.

5.1.5.1 Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED)

CPTED is a method of situational crime prevention that is based on the premise that the proper design and effective use of the built environment can lead to a reduction in crime and an improvement in the quality of life.

CPTED principles related to access management, such as natural surveillance, are considered a logical first step in improving security. Natural surveillance is a design strategy intended to facilitate observation of activities taking place on a site. Designing for natural surveillance involves providing ample opportunity for legitimate users, engaged in their normal activities, to observe the spaces around them.

To reduce the need for guards and technology, agencies should consider a CPTED strategy that takes advantage of as many architectural elements as possible, such as appropriate building layout and pedestrian flow, lighting, landscaping, and surveillance. Architectural design strategies are discussed in more detail in the Security-Oriented Design Considerations for Transit Infrastructure section of the FTA Transit Security Handbook.2

2Transit Security Handbook, Federal Transit Administration, FTA-MA-90-9007-98-1, Volpe Center, Cambridge, MA. March 2, 1998. http://transit-safety.volpe.dot.gov/Publications/Default.asp.

go to top of the page

5.1.5.2 Access Control

Access control is the ability to determine who can or cannot enter specific fields, areas or access particular assets or information. It is the fundamental principle of access management, and an important aspect of an effective security system.

| Transit Employee Security Awareness Frontline transit employees are the eyes and ears of every transit system. Bus and rail operators and maintenance employees, with the appropriate training, can be crucial in deterring, diffusing and responding to serious security incidents occurring on-board their vehicles and within transit stations or facilities. FTA funds and supports a wide variety of safety and security training to transit agencies. Employee and public security awareness are two of FTA's focus areas. FTA-sponsored training is developed in collaboration with transit industry professionals, industry experts, and professional training institutes. One course example is the National Transit Institute's (NTI's) System Security Awareness for Transit Employees. |

Access control relies on a combination of physical elements (barriers, portals, credentials) and policies (asset classification, credentialing) to operate properly. For more details on individual access management tools, refer to Section 5.2.

5.1.5.3 Intrusion Detection and Surveillance

Intrusion detection is the ability to know when someone has entered a secured area, and may include the ability to determine the identity of that person. This tracking of movement includes both authorized and unauthorized activity, and therefore can serve as both a staff management and a security tool.

Surveillance is the ability to monitor a specified area. This may occur through an on-site staff member or via remote technologies, such as closed-circuit television (CCTV). Surveillance systems vary in terms of detecting and recording capabilities. Individual surveillance components are discussed in Section 5.2.

5.1.5.4 Layered Security

The concept of layered security allows multiple opportunities for thwarting or disrupting terrorist activities and is a key aspect of an effective access management strategy.

Some antiterrorist measures are active defense measures. Highly visible security forces and security countermeasures could convince terrorists they will be unable to carry out their "attack sequence" of Target, Surveille, Plan, Rehearse, Execute, Escape, and may reduce the likelihood of an attack. Use of these high-visibility measures may cause terrorists to change their methods or switch to a more lightly defended target, requiring agencies to frequently reassess total target vulnerability.

Counter-surveillance is also a fundamental part of layered security. The conduct of extensive target reconnaissance is a common procedure for most terrorist groups. Mitigation of these attacks involves detection of the intentions of the terrorist-recognizing and reporting pre-incident indicators of a pending attack. Employees and security forces must be aware that surveillance is possible, understand the need to counter it, and be able to detect and report it. For example, when entry point personnel are equipped with cameras they become a more effective countermeasure, and are able to photograph persons or vehicles suspected of surveilling a location.

Security measures implemented at several different levels ("layers") throughout a facility help provide redundancy. The concept of layered protection recommends placing the most critical or most vulnerable assets in the center of concentric levels of increasingly stringent security measures (refer to Figure 5-2). For example, a transit facility's operations control room should not be placed right next to the building's reception area. Instead, where feasible, it should be located deeper within the building so that, to reach the control room, an intruder would have to penetrate numerous rings of protection, such as a fence at the property line, a locked exterior door, an alert receptionist, an elevator with key-controlled floor buttons, and a locked door to the control room.

|

|

Figure 5-2. Layers of Security |

|

Figure 5-3. Access Management Component Integration |

5.1.5.5 Systems Integration

Integrated access management systems allow transit agencies to monitor, detect, and respond to events more effectively. Systems integration streamlines management functions and improves the ability to secure assets by moving access management beyond the use of isolated security technologies to a setup in which the systems share information and act in concert.

Figure 5-3 shows potential integration opportunities for access management components. A transit agency with integrated access management systems for such functions as intrusion detection, surveillance, access control, and credentialing can monitor individuals' movements within restricted areas, and through points of entry and exit.

5.1.6 Implementation Challenges

Transit agencies face many challenges when implementing access management systems. Key areas to consider include:

Cross Institutional Issues

Access management cuts across many disciplines: engineering and design, construction and maintenance, traffic engineering, law, right-of-way, real estate, disability access, and transportation and land use planning. It is important that all the individuals responsible for each of these functions are involved at the program and/or the project level. Access management also brings significant political and institutional issues to the surface.

| Designing System Security Designing security into the system is easier and cheaper than patching it on later-security managers should be involved in the planning for all new construction and retrofit projects |

Incorporating Security Considerations Early

The ability to manage access effectively is often a function of the extent to which access management is considered in the planning stages, when agencies have the greatest opportunity to get results that are most in line with the recommended standards and guidelines established in their programs. The bigger challenge occurs when there has been little or no consideration given to managing access, requiring the retrofit of access controls, which is typically a long and challenging process.

Institutional Issues and Philosophical Differences

Access management initiatives, like all efforts to strengthen transportation security, face several long-term institutional challenges that include: (1) developing a comprehensive risk management approach; (2) ensuring that funding needs are identified and prioritized and that costs are controlled; (3) establishing effective coordination among the many responsible public and private entities; (4) ensuring adequate workforce competence and staffing levels; and (5) implementing security standards for transportation facilities, workers, and security equipment.3

3GAO. Post September 11th Initiatives and Long-Term Challenges. GAO-03-616T. March 31, 2001. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d03616t.pdf

Funding

Two key funding and accountability challenges for agencies include: (1) paying for increased access management; and (2) ensuring that these costs are controlled. The costs associated with acquiring equipment and personnel for improving transit security are significant. Many of the planned security improvements for transit facilities require costly outlays for infrastructure, technology, and personnel at a time when weakening local economies have reduced local transportation agencies' abilities to fund security improvements. Most of the technologies and policies associated with access management are scalable, however, making it possible for transit agencies to design individual access management programs that meet their own needs and available resources.

Legal Issues

Legal issues abound in the access management arena. Transit agencies and other organizations are increasingly concerned about the threat of being found liable as a result of security negligence. For example, any agency that installs CCTV without an effective policy for monitoring, recording, and managing the captured images could be held responsible for negligence. Likewise, an agency that uses vehicle barrier devices without providing proper employee training runs the risk that an individual or automobile will be injured by one of the barriers. Furthermore, organizations that do not implement or enforce existing security policies may find these policies to be a liability. For these reasons, efforts to avoid liability due to security negligence must be at the forefront of any security strategy.

Agencies must also consider how to respond to requests for information that may compromise security, whether such requests are a result of freedom of information requests or of competitive bidding processes. Legal and policy staff should consider which documents should be released at various stages of such processes, and how to ensure that the requesting party understands the sensitivity of the information.

Agencies that outsource components or processes of their security program to security-service providers should consider a close read of their service contracts to fully understand the liability implications. Comprehensive integrated security systems can be the best "liability insurance" money can buy:

- The cost of business property theft, employee theft, and computer crime is skyrocketing.

- Limited resources mean cutbacks on what local law enforcement can do.

- Security-related litigation (based on claims that existing security was "inadequate") is producing average awards in excess of $1 million. 4

4Cunningham, William C., Taylor, Todd H. The Hallcrest Report I: Private Security and Police In America. National Institute of Justice. June 1985.

Many security suits relate to:

- Inadequate security personnel

- Inadequate lighting

- Non-operable equipment

- Faulty equipment

- Promised security when there is no security (brochures and advertisements promising security)

- Negligent retention and training of security personnel

Other legal issues to consider include the growth of privacy as a global issue, and the possible illegality of many access management countermeasure devices in some geographic areas.

5.2 Tools/Techniques

This section provides an overview of tools and techniques transit agencies can use to manage access. These include:

- Policies and procedures

- Perimeter protection and physical barriers

- Entry-point screening

- Credentials and credentialing

- Surveillance systems

- Intrusion-detection systems (IDS)

- Security personnel

- Communications and information processing systems

- Lighting

When used effectively, these tools and techniques create an adaptable network of security measures, with a high degree of interaction among subsystems, and the ability to evolve over time in response to changing security requirements and technologies. Refer to Section 5.3 for sample access management guidelines, with details on specifications and deployment strategies.

5.2.1 Policies and Procedures

| What kinds of procedures are necessary? Agencies should consider an up-to-date access management plan that lists the functional requirements for access management systems, as well as standard operating procedures that address contingencies for security issues that may arise. |

A crucial aspect of access management and of security systems in general, is the need for an effective set of administrative policies and procedures establishing the various system elements and security functions. The policies establish the relationship between groups of users and sets of assets, and permit or deny different users' access to certain assets.

Agencies must have an up-to-date access management plan that lists the functional requirements for access management systems, as well as standard operating procedures that address contingencies for security issues that may arise. Security personnel must have clear, effective procedures to perform their duties well. Access management policies and procedures should be based on the results of a system-wide TVA. Refer to the FTA's Public Transportation System Security and Emergency Preparedness Planning Guide for a step-by-step description of conducting a TVA.5

5The FTA's Public Transportation System Security and Emergency Preparedness Planning Guide (2003) describes the steps in conducting a TVA. http://transit-safety.volpe.dot.gov/Publications/security/PlanningGuide.pdf

5.2.2 Perimeter Protection and Barriers

Barriers can be used to define property boundaries and to enclose secured areas. Physical barriers include any objects that prevent access into a restricted area or through an entry portal, including fences, doors, turnstiles, gates, and walls.

There are two categories of physical barriers: admission control and perimeter control.

- Admission-control barriers are those used at entry points to selectively allow people to pass through. The most common admission-control barriers are swing doors, revolving doors, turnstiles, and portals. These may be operated mechanically or electronically in conjunction with electromagnetic door locks, keypads, or other entry-point screening mechanisms (refer to Section 5.3).

- Perimeter-control barriers establish a secure boundary around an area, and limit access to and from that area to admission-control points. They can be constructed from a variety of materials, and may be designed to prevent some types of movement while permitting others (such as bollards that block motor vehicles while enabling pedestrians to pass through). Barriers can be placed to direct passenger flow and deter access to isolated or hidden locations.

A common and effective type of physical barrier for perimeter control is chain-link fencing with barbed wire. It is flexible and easy to erect around any size and shape of structure and along rights-of-way and bridges and is also relatively inexpensive to install. Agencies should consider inspecting fence line regularly for integrity and repairing any damage promptly. Fences and other simple barriers, such as walls, can be enhanced with intrusion-detection or CCTV systems, to improve their effectiveness at preventing unauthorized access (see Sections 5.3.5 and 5.3.6).

Shrubbery and landscaping decisions along a perimeter should be based on maintaining visibility for surveillance purposes. Building walls, floors, and roofs may form part of the barrier and should be designed to provide security equivalent to that of the security barrier. Details on perimeter designs and strategies are covered in Chapter 6: Infrastructure. Sections 6.2.1 and 6.2.2 describe the design of the site and interior layout. 6.3 describes design-related security strategies for perimeter security at fixed sites and facilities (the transit infrastructure) within a system, organized by type of asset, such as transit stations and tunnels, with subsections on perimeter security for each asset. "The Security-Oriented Design Considerations for Transit Infrastructure" chapter of the FTA Handbook also has additional information about perimeter designs and strategies.6

5.2.3 Entry-Point Screening

A critical part of the access control function is entry-point screening; a method for enforcing selective admission at entrances and other access points. Entry-point screening typically involves secure/non-public areas within a transit system, and can entail verification of identity, a physical search of belongings or a vehicle, x-ray search of bags and packages, weapons detection of both belongings and people, explosives detection, or chemical/biological agent screening. Although high ridership volume, limited space, and the limited throughput of current metal detection screening technologies would not allow mass screening of all passengers in transit stations without severely impacting service, transit agencies may use screening at key high-security facilities/areas, or may selectively screen for high-risk individuals, locations, and events.

For transit agencies, entry control, i.e., allowing or denying entry, may have more immediate relevance and success in non-public facilities and areas, such as operations centers, maintenance facilities, and special equipment rooms in stations, when combined with an automated admission-control device. Entry-point screening is particularly beneficial with temporary or occasional workers and visitors.

Transit agencies can utilize variable levels of entry control:

- A security guard controls entry; ID cards or other means of identification may be checked.

- An agency-provided special ID card/badge to work with automatic readers (based on what you HAVE).

- A code, such as a personal identification number (PIN), for entering on a keypad (based on what you KNOW)

- A biometric device for feature recognition, such as fingerprint identification (based on who you ARE).

Each approach offers different level of security, has different labor requirements and uses different technologies (see Figure 5-4).

|

Figure 5-4. Entry Control Techniques |

Access control technology is advancing rapidly; many of the biometric devices currently in use were not available until recently. When used in conjunction with physical barriers and CCTV (see Section 5.2.5), access control systems enable security personnel to monitor and protect vital assets, such as power facilities, control centers, and computers, more effectively. Electronic access control systems, such as key card systems, have the advantage over conventional key systems in that lost or revoked credentials can be immediately deactivated with minimal cost. In addition, automated entry-point screening systems can sometimes replace guards at some entrances.

Material screening systems complement access control measures. Access control limits who enters a facility or a secured area, while screening systems limit what enters those areas. Screening systems can detect the presence of prohibited items, such as weapons, explosives, or chemical/ biological/nuclear/radiological (CBNR) materials. They utilize a range of technologies (such as x-ray machines and metal detectors), and can be deployed at entry points or throughout a facility.

5.2.4 Credentials and Credentialing

| TSA's Transportation Worker Identification Credential (TWIC) The TWIC is a uniform identification credential for all transportation workers requiring unescorted access to secure areas at transportation facilities including mass transit. The TWIC works with multiple types off access control points (vehicle gates, building, and door access) as well as multiple access control technologies (smart chips and barcodes). Credentialing covers physical and logical access for individuals. Access management-related steps include establishing a secure ID, background checks and credentialing, enrollment, data management and procedures. |

Credentials and credentialing are key components for an agency's access control system.

5.2.4.1 Credentials

Credentials are physical objects used to gain admission at entrances or other access points, such as identification cards, badges, card keys or physical attributes.

A credential signifies that an individual's qualifications have been assessed and validated. Whether the credential is a simple badge with a picture presented for sight identification or a "smart" card that can be used to gain physical access to secure areas or to gain virtual access to computer networks, it is the key to the access control system.

A credential can work on several levels. Security workers may visually inspect credentials using graphics, colors, pictures, and text to help identify personnel and their access to restricted areas. The credential may electronically identify the holder to the security system, which checks a data base to ensure the credential holder has the required clearance. There may also be additional personal information about the cardholder on the credential or in a central database, including biometric data or a Personal Identification Number (PIN) that must be entered at a reader. Examples of biometric technologies are fingerprint, iris scan, retinal scan, hand geometry, face scan, voiceprint, and signature.

5.2.4.2 Credentialing

Credentialing is the issue and management of credentials, as well as the procedures used to make decisions about granting credentials to particular individuals.

Credentialing typically includes the process of reviewing individuals' qualifications, to assess whether they should be granted access to buildings, facilities, secured areas, or computer networks. Agencies should consider assigning a security classification to each part of the system, and identifying the types of users accessing each part. Many agencies also perform some form of background check before the credentials are issued, ranging from viewing a photo ID, to performing a criminal wants and warrants check, or even an intense background check with interviews. The more important the areas to which an individual will have access, the more stringent and periodic the background check may have to be. Figure 5-5 illustrates the credentialing process for access control.

|

Figure 5-5. Credentialing and Access Control |

Credentialing is an important access management tool. In the transit environment, its use is limited to individuals employed or contracted (including concessionaires) by the agency, and to some visitors at administrative facilities. Permanent employees, temporary employees, visitors requiring escort, and visitors not requiring escort are examples of users for whom different types of credentials may be needed.

A Transit TWIC Secure Area is an area of a public transportation operation where the local operator:

Secure areas may include: Dispatch/Control Facility; Bus Engine Compartment/Mechanical Areas; Maintenance Facility/Garage/Yard; Central Control Facility; Law Enforcement Facilities; Revenue Rooms; Revenue Transport Train/Truck, Power Cabinets, Switch/Signal Cabinets; HVAC systems; Fuel Storage Facilities; Confidential Records Repositories; Agency Chief Operating Officer's Offices |

5.2.5 Surveillance Systems

| Surveillance Observation methods either carried out by humans or with the assistance of technology |

By deploying remote CCTV surveillance systems, agencies can expand the areas in and around transit facilities monitored by security personnel. CCTV surveillance systems may include fixed cameras and pan/tilt/zoom cameras that security personnel can remotely control, and often include video-recording systems. In addition, the visible presence of surveillance cameras in an area can serve as a deterrent to potential intruders who believe they are being observed.

Agencies should be aware of the labor intensity of watching banks of monitors, be cautious about relying on CCTV beyond their ability to monitor activities, and should consider the use of event triggered surveillance. For example, pairing remote-surveillance with intrusion-detection systems (see Section 5.2.6) results in event-triggered surveillance, which may be particularly useful for vulnerable areas that might not otherwise require constant observation, such as tunnel portals or power substations.

When combined with a videotape or digital recording system, a surveillance system can provide vital information about security events. Responders can use the video information to apprehend intruders or to communicate descriptions of intruders to law enforcement agencies. In addition, the video record can potentially be used as evidence in a trial, provide investigators with information about the causes of events, and discourage future occurrences. Videotape evidence can improve the likelihood that an alleged criminal is convicted in a court of law. Agencies must follow local and state requirements for the auditing, handling, storage, and retention of such materials. Some jurisdictions require that it be possible to trace any recorded images to a specific date, time, recording device and recording medium and operator. New rules being introduced relating to the submission of CCTV video recordings as evidence state that it must be proven that a videotape has been completely erased before being reused. Failure to comply with data protection requirements may affect the police's ability to use CCTV images to investigate a crime and may hamper the prosecution of offenders.

It is important to note with the installation of a surveillance system, particularly one including CCTV technology, the agency may have to consider developing a privacy policy to manage the use of any images or sounds recorded by the system.

5.2.6 Intrusion Detection

| Intrusion-Detection Systems Integrated electronic components for detecting intrusion into a protected area and alerting response forces |

An IDS is a combination of integrated electronic components, including sensors, control units, transmission lines, and monitoring units, that detect one or more types of intrusion into an area protected by the IDS. An IDS includes both interior and exterior systems, and may also include electronic entry control devices and CCTV for alarm assessment.

IDSs can be useful throughout transit system operations, allowing security personnel to monitor the movements of authorized people in restricted-access areas and to alert security personnel of potential breaches by unauthorized persons. At perimeters IDSs provide improved security-response time. Pairing intrusion-detection systems with remote surveillance technology enables event-triggered surveillance. For more information on intrusion detection for tunnels, refer to Section 6.3.6.

There are numerous types of interior and exterior sensors that agencies can deploy to signal security personnel when an intruder crosses a threshold, opens a door, or breaks a window. These include area sensors, barrier sensors, point sensors, and volumetric sensors. Intrusion sensors may be buried in the ground or mounted to a fence, wall, ceiling, floor, door, or window. Sensing technologies include magnetic or mechanical switches, pressure sensors, infrared sensors, acoustic sensors, and video cameras.7

7The TCRP program has prepared a detailed report on intrusion-detection systems that offers a detailed review of the advantages and disadvantages of many technologies. Intrusion Detection for Public Transportation Facilities Handbook, Transit Cooperative Research Program, March 2003.

5.2.7 Security Personnel

| Security Personnel ... security force roles have (shifted) from crime-prevention and safety to ensuring the security of the transit system and riders against terrorist attacks. |

Many transit agencies, particularly the larger ones, deploy their own security forces to patrol facilities. Since the September 11, 2001 attacks, roles of security forces have been shifting from prior focus on crime-prevention and safety to also ensuring the security of the transit system and riders against terrorist attacks.

Security personnel are responsible for carrying out access management policies and procedures and for overseeing and operating the access control systems used. Functions performed by security personnel can include:

- Identification checks - visually inspecting badges, credentials, or other forms of identification. Entry-point screening - visually inspecting bags and parcels, vehicles, operating metal detectors and x-ray machines, etc.

- Monitoring security systems - monitoring surveillance cameras, digital video, intrusion detection, and other security systems.

- Patrols - patrolling on foot or in a vehicle to ensure that doors are locked and fences and gates are secured. Patrols visually inspect buildings and grounds and can provide a human presence to deter intruders. A patrol can also include a K-9 component to provide additional deterrence and detection.8

- Response - responding to alarms or unauthorized entry.

- Communications - contacting law enforcement and emergency response personnel.

8Balog, Bromley, et al. K9 Units in Public Transportation: A Guide for Decision Makers. TRB TCRP Report 86: Public Transportation Security. Transportation Research Board National Research Council Volume 2: 2002.

| Communication Systems Enable person-to-person communications and can link various access management subsystems into a networked security system. Information Processing Systems Coordinate activities, record incident data, provide audit trails, and generate reports. |

5.2.8 Communication and Information Processing Systems

Communication systems are vital because they ensure that information about incidents can be sent to appropriate persons. These systems enable person-to-person communications and can link various access management subsystems into a networked security system.

Communications links can be established using any number of modes or combinations of modes, including telephone, cell phone, fax, e-mail, Web site, radio, intercom, wired, wireless, fiber optic, PDA or pager to transmit voice, data, and/or video. On-site security personnel can use communications systems to summon police or other appropriate emergency response organizations when necessary. Reliability, redundancy, and security of communications links are important to the overall success of a security system. Refer to the chapter on "Security-Oriented Design Considerations for Transit Communications" in the FTA Handbook for additional information.9

Information processing systems are also an integral part of many security systems. Consisting of a combination of hardware and software, including computers, data bases, and workstations, they are used by security personnel to coordinate activities, record incident data, provide audit trails, and generate reports. Information systems make possible central control and maintenance of user access, authorization, and authentication. They are also used within systems for signal processing and monitoring, and for managing many control systems.

9Ibid. http://transit-safety.volpe.dot.gov/Publications/Default.asp

5.2.9 Lighting

Lighting increases visibility in and around transit facilities, and makes it more difficult for intruders to enter a facility undetected. It is beneficial in almost all environments, especially those that receive little natural light or are used at night. Agencies should consider lighting when installing and updating other access management subsystems, particularly those that utilize surveillance and intrusion detection. In accordance with CPTED principles, lighting can also be used to create greater levels of comfort for passengers and staff present in transit facilities. See Section 5.3.2 for additional information about lighting systems and standards.

5.3 Sample Access Management Guidelines

Transit system operators have the primary responsibility for ensuring their systems and facilities are secure. This section presents sample guidelines for various access management security measures. The intent is to provide information that will assist transit facility operators in understanding and managing risks to their facilities and other assets. These guidelines are also intended to make transit agency managers aware of the major areas that should be addressed in an access management policy and plan, and which standards and procedures should be established.

The guidelines are not exhaustive; they are an outline of general approaches to access management and are a useful resource, but each agency must identify its particular security needs and determine which access management measures are appropriate. Agencies also should consider the differences in threat levels and/or particular circumstances among various geographic areas or facilities. Some guidelines are more appropriate for non-public transit facilities - administrative offices, maintenance yards, and operations control centers; others could be effectively implemented in stations, parking lots and garages, and other facilities open to and used by the public. Some guidelines are best implemented in new transit infrastructure; others can be easily included as part of a retrofit or reconstruction. The bottom line is that agencies should make access management decisions on a case-by-case basis to meet the needs and available resources of their individual transit agency.

Guidelines are summarized for the following access management areas:

| The guidelines outline general approaches to access management and are a useful resource, but each agency must identify its particular security needs and determine which access management measures are appropriate. |

- Fencing and gates

- Security lighting

- Admission control

- Vehicle access control and parking

- Vehicle barriers

- Critical/restricted area access

- Windows

- Wall safeguards

- Miscellaneous openings

- Personnel security

- Key control

- Security force

Note that details on asset management design and strategies are beyond the scope of this chapter and are covered in Chapter 6: Infrastructure. 6.2 is an overview of design considerations for fixed sites and facilities (the transit infrastructure) within a system. 6.3 describes design-related security strategies.

5.3.1 Fencing and Gates

Agencies should consider these guidelines when installing, maintaining, and controlling perimeter fences, clear zones, fence fabric, posts and hardware, openings, and gates.

Design considerations - refer to Section 6.2.1 Security strategies - refer Perimeter Security subsections in Section 6.3 |

5.3.1.1 Perimeter Fences

Perimeter fences define the physical limits of a facility or controlled area; provide a physical and psychological deterrent to unauthorized entry; channel and control the flow of personnel and vehicles through designated portals; facilitate effective utilization of the security force; provide control capability for persons and vehicles through designated entrances; and enhance detection and apprehension of intruders. Fencing can be used as a barrier in various locations:

- Perimeters of property parking lots and structures

- Bus yards, maintenance depots, etc.

- Vital facilities (power, fuel, etc.)

- Along track/right-of-way

- Pedestrian bridges

Fencing can range from high-security grill type fencing to cost-effective chain-link fencing. If the security threat is lower or if aesthetics are a high priority, ornamental fencing can also be used if it is properly designed to prevent scaling. Typical fence requirements include:

- Perimeter fences and other barriers should be located and constructed to prevent the introduction of persons, dangerous substances or devices, and should be of sufficient height and durability to deter unauthorized passage.

- Areas adjacent to fences and barriers should be cleared of vegetation, objects and debris that could be used to breach them, or hide intruders.

- Boxes or other materials should not be allowed to be stored/stacked against or in close proximity to perimeter barriers.

- The fence line needs to be inspected regularly for integrity and any damage needs to be repaired promptly.

- Whenever locations permit, fencing should be located not less than 50 feet (15.2 meters) or more than 200 feet (61 meters) from the asset being protected.

- Any opening with an area of 96 square inches (619 sq cm) or greater, and located less than 18 feet (5.5 meters) above ground level outside the perimeter or less than 14 feet (4.3 meters) from controlled structures outside the perimeter barrier, should be provided with security equivalent to that of the perimeter.

- If a body of water forms any part of the perimeter barrier additional security measures should be provided.

- A fence that is at least 4 feet (1.25 meters) high can be used as a barrier to guide pedestrian movements.

Although low-level risks may be controlled with a perimeter fence, fences alone will not stop a determined intruder or a moving vehicle attack, and will resist impact only if reinforcements are added. To control identified risks, agencies should enhance the effectiveness of fencing with lighting, CCTV, fence sensors to detect climbers or cutting actions, and/or augmented by security force personnel. A fence that is not protected with intrusion-detection equipment may be vulnerable to attack and unauthorized access if it is not under constant surveillance by security personnel.

5.3.1.2 Clear Zones

Clear zones for security fences should meet the following requirements:

- Fences should be constructed so that an unobstructed area or "clear zone" is maintained on both sides of the barrier to make it more difficult for a potential intruder to be concealed from observation.

- Whenever practical, exterior and interior clear zones should be 20 feet (6 meters) or more. The clear zone should be free of any object or feature that would offer concealment, such as a physical structure or parking area, or which could facilitate unauthorized access such as an overhanging tree limb.

- When a clear zone is not practical, other compensatory measures may be necessary to control access to secured areas. Appropriate supplemental protective measures include increasing the height of portions of the fence, providing increased lighting, CCTV surveillance cameras monitored from a remote location, installation of intrusion-detection sensors and security patrols.

5.3.1.3 Fence Fabric

The most common type of physical barrier for perimeter control is chain-link fencing, often installed with barbed-wire outriggers. It is flexible, relatively inexpensive, and easy to install around any size and shape of structure/security zone. These guidelines focus on chain-link fencing, but agencies should look at alternatives, such as expanded metal fencing in areas of greater risk, e.g., where vandalism is high.

Fencing fabric should meet the following requirements designed to increase fence performance:

- Fences, including gate structures, should be number 9-gauge or heavier chain-link fabric. Fabric should be aluminum or zinc-coated steel wire chain link with mesh openings not larger than 2 inches (5.08 cm) on a side.

- Fence fabric should be attached to the exterior side of line posts using not less than 9-gauge steel ties.

- Fence height should be a minimum of 8 feet (2.4 meters) to deter unauthorized passage. This includes a fabric height of 7 feet (2.1 meters) plus a barbed-wire/razor wire outrigger extension of 1 foot (0.304 meters).

- The distance between the bottom of the fence fabric and firm packed ground should not exceed 2 inches (5.08 cm).

- When the fencing is being installed on soft ground, the fabric should reach below the surface sufficiently to compensate for shifting soil. To prevent individuals or objects from going under the fence, a cement apron not less than 6 inches (15.2 cm) thick can be installed under the fence. The fence fabric can also be extended below the bottom rail and set in the concrete. Exposed surface of concrete footings should be crowned to shed water.

- Pipe framing can be installed on the fabric where it touches the ground, or 2-foot (0.6 meter) long U-shaped stakes can be used to fasten the fabric to the ground. Fence fabric should be attached to terminal posts with stretcher bars that engage each fabric link. The stretcher bars should be held to the fence post with clamps in such a way as to hold the fabric taut.

- If exterior intrusion-detection systems are to be mounted, the maintaining of constant fabric tension (minimum horizontal tension of 1,000 pounds) will greatly reduce sensor vibration.

- A tension wire should be stretched from end to end of each section of fence and fastened to the fence fabric within the topmost 12 inches (30.5 cm). Taut reinforcing wires, a minimum of 9-gauge, should be installed and interwoven with or affixed with 12-gauge fabric ties spaced 12 inches (30.5 cm) apart along the top and bottom of the fence fabric.

- Salvage should be twisted and barbed at top and bottom.

- Metal fencing should be electrically grounded.

- If a masonry wall is used as the perimeter barrier, it should be at least 7 feet (2.1 meters) in height with a top guard of barbed wire or at least 8 feet high with broken glass set on edge and cemented to top surface.

- If building walls, floors, or roofs form a part of the perimeter barrier, all doors, windows, and openings on the perimeter side should be properly secured.

5.3.1.4 Posts and Hardware

All fence posts, supports, and hardware for security fences should meet the following requirements:

- All fastening and hinge hardware should be secured against attempts at unauthorized removal by penning or spot welding to allow proper operation of the components but deter disassembly of fence sections or removal of gates.

- The bolts securing the clamps to the posts should be penned or otherwise modified in a manner to deter attempts at unauthorized removal.

- All posts and structural supports should be located on the interior of the fence. Posts should be spaced not more than 10 feet (3 meters) apart and should be embedded in bell-shaped concrete footings to a depth of 3 feet (0.61 meters) to prevent shifting or sagging.

5.3.1.5 Openings

Agencies should consider the following requirements for maintaining the fence's integrity when traversing culverts, troughs, ditches, or other openings:

- Openings should terminate well within the secure area defined by the perimeter security fence barriers.

- If perimeter security fence barriers must traverse culverts, troughs, ditches, or other openings 96 square inches (619.4 sq cm) or greater in area and larger than 6 feet (1.8 meters) in any one dimension, the opening should be protected by an extension of the fence construction. This extension may consist of iron grills or other barrier structures designed to prevent unauthorized access.

- Bars and grills should be installed in such a way that they do not impede required drainage. Hinged security grills used with an approved high security hasp, shackle, and padlock, which can be opened when necessary, are often a workable solution to securing drainage structures.

5.3.1.6 Gates

Perimeter Gates

The number of perimeter gates designated for active use should be kept to the absolute minimum required for operations. Agencies should take into account sufficient entrances to accommodate the peak flow of both pedestrian and vehicular traffic, as well as adequate lighting at egress and ingress points (refer to Section 5.3.2.2).

- Gates should be of such material and installation as to provide protection equivalent to the perimeter barriers of which they are a part.

- The space between the bottom edge of the gate and the pavement or firm ground should not exceed 2 inches (5.08 cm).

- All entry gates should be locked and secured or guarded at all times or should have an effective entry detection alert system.

- Gates over 6 feet (1.83 meters) in height should have locks at the top and bottom to ensure that the gate cannot be pried open a sufficient distance to allow unauthorized entry.

- Vehicular gates should be set well back from the public highway or access road in order that temporary delays caused by identification control checks at the gate will not cause undue traffic congestion.

- Sufficient space is provided at the gate to allow for spot checks, inspections, searches, and temporary parking of vehicles without impeding traffic flow.

- At least one vehicle gate that is at least 14 feet (4.3 meters) wide for each enclosure should be provided to permit entry of emergency vehicles.

- For facilities employing a security force, a security guard house can be provided at the site perimeter for permanent manned gates.

- Fenced facilities employing electronic card access systems should consider configuring the main employee entrance gate with an automated entry control system with CCTV for visual assessment capability.

Unattended/Inactive Gates

Agencies should consider the following requirements for unattended/inactive gates:

- Unmanned gates should be securely locked at all times.

- Security lighting should be provided to deter attempts at tampering during the hours of darkness.

- Perimeter intrusion-detection system (PIDS) and CCTV protective measures are appropriate when necessary to meet identified risk control requirements during those periods when the gate is not under the direct visual observation and control of a security officer.

5.3.2 Security Lighting

Security lighting increases visibility around perimeters, buildings, storage tanks, and storage areas, loading docks, as well as in buildings, hallways, and parking lots. It is a security management tool that is applicable in almost all environments within a transit system, and should be considered when agencies are installing and updating other access management sub-systems, particularly those focusing on surveillance. Security lighting allows the security force to visually monitor the lighted areas, making it difficult for someone to enter the facility undetected, and facilitating the apprehension of offenders. Determining which system is appropriate for a given application depends on the identified risk control requirements of the facility. For a description of types of security lighting, refer to Section 5.3.2.3.

At a minimum, all access points, the perimeter, restricted areas, and designated parking areas should be illuminated from sunset to sunrise or during periods of low visibility. In some circumstances, lighting may not be required, but these circumstances must be addressed in the facility security plan. The plan must show that the absence of lighting will not adversely impact risk and should include the alternative measures being used. Agencies should understand that undesirable shadowing will exist, and the total elimination of shadowing is not practical in all areas.

However, lighting need also be appropriate to the operating environment. Agencies should consider the environment where stations and other infrastructure are located, so as to make lighting appropriate to the area. More residential environments may be less receptive to bright, consistent lighting. Agencies should consider methods of making lighting safe, attractive and neighborhood-friendly, such as high-level, indirect lighting, multiple low-level lights, or some combination of both.

Design considerations - refer to Section 6.2.5.5. Security strategies - refer to 6.3.1. transit stations, 6.3.2 transit stops, 6.3.3. administrative buildings/OCCs, 6.3.5 elevated structures, 6.3.6 tunnels |

- Facilities should be illuminated to an acceptable industry standard, such as the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America (IESNA) or other recognized industry standard.

- To provide better visibility, updated lighting technology should be used. For CCTV compatibility, consider metal halide lighting.

- Lighting should be directed downward and should produce high contrast with few shadows.

- Illumination is recommended whenever possible, but equivalent measures such as motion detectors or intrusion alarms may be used to monitor areas at facilities where perimeter illumination is unpractical.

- In some circumstances, it may be preferable to use lighting systems only in response to an alarm or during specific operations.

- Portable floodlights may be used to supplement the primary system.

- When used, portable floodlights should have sufficient flexibility to permit examination of the barrier under observation and adjacent unlighted areas.

- Controls, switches, and distribution panels for security lighting should be located in restricted areas, weatherproofed, protected to prevent unauthorized access or tampering, readily accessible to security personnel, and inaccessible from outside the perimeter.

- Wiring for security lighting should be in tamper-resistant conduits, preferably underground; if above ground, wiring should be high enough to reduce the possibility of tampering.

- Critical facilities should provide a secondary power supply line(s) separated from the primary power line(s). The facility should have the ability to rapidly switch to the secondary power line(s) during power failures. Security lighting systems should be independent of the general transit facility lighting or power system.

- Power supplies for security lighting should be adequately protected.

- Standby/emergency lighting should be tested per industry standard, for example: monthly for a duration of 30 seconds and annually for a duration of 1 1/2 hours.

- Inoperative lights and lamps should be repaired/replaced immediately.

- Materials and equipment in storage areas should not mask security lighting.

Agencies should consider these lighting guidelines for perimeter lighting and for entry, guardhouse, and parking lot lighting.

5.3.2.1 Perimeter Lighting

- Where perimeter lighting is required, the lighting units for a perimeter fence should be located a sufficient distance within the protected area and above the fence so that the light pattern on the ground will include an area both inside and outside the fence.

- Perimeter lighting should be continuous and on both sides of the perimeter fence and should be sufficient to support CCTV and other surveillance equipment where required.

- The cone of illumination from lighting units should be directed downward and outward from the structure or area being protected. Cones of illumination should overlap to provide coverage in the event of bulb burnout.

- The lighting should be arranged so as to create minimal shadows and minimal glare in the eyes of security guards.

5.3.2.2 Entry, Guardhouse, and Parking Lot Lighting

Entry/Guardhouse

- All vehicle and pedestrian entrances to the facility should be illuminated.

- Lighting at manned entrances must be adequate to identify persons, examine credentials, inspect vehicles entering or departing the facility premises through designated control points (vehicle interiors should be clearly lighted), and prevent anyone from slipping unobserved into or out of the premises.

- Entry lighting should be sufficient to allow for personnel identification during times of darkness and extreme environmental conditions.

- Lighting intensity at entrances should be planned to ensure that arriving drivers can readily recognize the premises and see where to drive their vehicle.

- Lighting should not be placed to cause blinding of the driver.

- Semi-active and unmanned entrances should have the same degree of continuous lighting as the remainder of the perimeter, except that additional, standby lighting should be available to provide the same illumination required for manned entrances when the entrance becomes active.

- Gate houses at entrance points should have a reduced level of interior illumination to enable the security guards to see better, increase their night vision adaptability, and avoid illuminating them as a target.

Parking Lot Areas

In addition to the security hazard of providing hiding places, unlit parking areas are vulnerable to thieves and can pose a risk of physical attack to employees and patrons.

- Parking areas should be provided with uniform illumination sufficient to allow for personnel identification during times of darkness and extreme environmental conditions.

Emergency Power

- Parking lot and entry lighting systems at facilities should be connected to the emergency power system, to ensure they remain operational during periods when commercial power is interrupted at critical facilities

5.3.2.3 Types of Lighting

There are four general types of security lighting systems: continuous, standby, moveable, and emergency. Determining which system is appropriate for a given application depends on the identified risk control requirements of the facility.

Continuous Lighting

Continuous lighting is the most commonly used form of security lighting systems, consisting of a series of fixed luminaries arranged to illuminate a given area on a continuous basis with overlapping cones of light during the hours of darkness. There are two primary types of continuous lighting:

- Glare Projection. This lighting is useful when the desired effect the glare of lights directed toward the exterior of the facility and into the eyes of a potential intruder. The lighting at gate entrance locations is an example. A vehicle approaching the gate during the hours of darkness is fully illuminated, but the guard station remains in the shadow of the light pattern.

- Controlled Lighting. This lighting is used most often at locations where it is necessary to limit the width of the lighted strip outside the perimeter fence because of nearby residential areas, public thoroughfares, or other activity centers. With controlled lighting, the width of the illuminated strip can be controlled and arranged as required. For instance, one possible configuration might be a wide band of illumination inside the fence and a narrower band on the exterior of the fence. The physical design of the luminaries allows the light source to be directed to achieve these results. The angle of the luminaries is primarily downward with some angle adjustment to attain the desired width. Fully shielded lighting (fixtures that emit no light above the horizontal direction) can also alleviate neighbor objections.

Standby Lighting

The arrangement of this lighting system is similar to continuous lighting and meets the same security lighting specifications, but is used only in certain circumstances. When a possible intruder is detected, the security system or guard force can activate the standby lighting system for extra illumination. It can also be deployed at unattended/attended gates for extra lighting. Standby lighting differs from the continuous lighting in that only security personnel or the security system software have control over the system.

Moveable Lighting

This lighting system consists of manually operated movable light sources and luminaries such as searchlights, which can be lighted during hours of darkness to cover specific areas as needed. Moveable lights are normally used to supplement continuous or standby systems.

Emergency Lighting

This lighting system may duplicate the other three systems in whole or in part. Its use is normally limited to periods of main power failure or other emergencies. While security lighting should be connected to an uninterruptible power system when possible, emergency lighting should depend on a separate, alternate power source, such as portable generators or batteries. Table 5-1 lists the standard illuminance in foot-candles for several security lighting targets.

Table 5-1. llluminance Specification

| Lighting Target | Illuminance | |

|---|---|---|

| Lux | Foot-candles | |

| LARGE OPEN AREAS (Standard System) | ||

| Average minimum illuminance | 2 | 0.2 |

| Absolute minimum illuminance | 0.5 | 0.05 |

| LARGE OPEN AREAS (Glare System) | ||

| Average minimum illuminance | 2 | 0.2 |

| Absolute minimum illuminance | 0.5 | 0.05 |

| SURVEILLANCE OF CONFINED (low ceiling / interior) AREAS | ||

| Average minimum illuminance | 5 | 0.5 |

| Absolute minimum illuminance | 1 | 0.1 |

| SURVEILLANCE OF VEHICLE OR PEDESTRIAN ENTRANCES | ||

| Average minimum illuminance | 10 | 1 |

| Absolute minimum illuminance | 2.5 | 0.25 |

| CCTV SURVEILLANCE | Varies with individual systems (Consult CCTV manufacturer) |

|

5.3.3 Admission Control

Admission control to non-public/secure areas of a transit system is essential. The most common admission control barriers are swing doors, revolving doors, slam gates, turnstiles, and portals. These may be operated mechanically or electronically in conjunction with electromagnetic door locks, keyboard and memorized codes, encoded cards and card readers, video comparators (with or without guard assistance) and biometric identifiers. Automated access control systems can sometimes reduce the number of security staff by replacing them at entrance points.

In addition to physical countermeasures, admission control relies heavily on following procedures. Agencies should follow these admission control guidelines for facility employees, contractors, and visitors; and pick-ups and deliveries.

Design considerations - refer to Section 6.2.1 Security strategies - refer to Human Access subsections in Section 6.3 |

5.3.3.1 Facility Employees, Contractors, and Visitors

Requirements for identification of facility employees, contractors, and visitors can include:

- All persons entering and/or leaving non-public/secure facilities/areas within the transit system should possess and show a valid identification card or document (as described below) to gain access. All passengers in vehicles must have valid identification. Identification must be presented to security personnel upon request. Security personnel or competent authority should verify that identification documents and applicable licenses or credentials match the person presenting them. In the event that an individual seeking access to the facility does not have an identification card that meets the requirements, only prescribed alternative means of identification should be accepted.

- As the threat level dictates, the facility should develop a verification process to ensure that all persons requiring access to the facility have valid business at the facility. Vendors, contractors, truck drivers, and visitors should be scheduled in advance to the maximum extent possible. If their arrival is not prearranged, entry should be prohibited until their need to enter is verified and vehicle inspected.

- Valid identification cards or documents must be tamper resistant and at a minimum include the holder's name and a recent photograph of the holder. Any of the following may constitute a valid form of identification:

- Employer-issued employee identification cards

- Identification card issued by a government agency

- State issued drivers license (note that some states do not require photos)

- Labor organization identity card

- Passport

- Guards should check vehicle drivers and passengers for proper identification, and check the vehicle for suspected bombs and suspicious packages. Persons arriving by motorcycle should be required to remove helmets to assist in identification. Guards should admit only authorized vehicles. Guards should detain visitors whose arrival is not expected at the entrance until cleared by authorized personnel.

- A record should be kept of non-transit agency vehicles permitted access to secure premises. Security personnel should randomly verify the identity and identification of persons encountered during roving patrols.

- The facility should have a process to account for all persons within the facility at any given time. Visitor identification should be displayed at all times and should be visually distinct from employee identification (orange is used by some agencies). Visitor ID should include an expiration date. Return of visitor IDs should be controlled and reconciled daily. Place visitor-accessible locations in buildings away from sensitive or critical areas, areas where high-risk or mission-critical personnel are located, or other areas with large population densities of personnel.

5.3.3.2 Pick-Ups and Deliveries

Security procedures for pick-ups and deliveries can include:

- Delivery orders should be verified prior to being allowed access to restricted areas. Shipping documents for deliveries should be checked for accuracy and items being delivered should be adequately described on documentation, including piece count if applicable.

- Pick-up and delivery appointments should be from known vendors only.

- Deliveries should be accepted only in designated areas.

- All packages entering or leaving the facility should be subject to search by security personnel. Signs should be posted at each access point to advise of this requirement.

- Facilities with a loading dock should have procedures in place to ensure that deliveries are supervised and not left unattended.

- Facilities employing a guard force should have guard force personnel notify facility management that a vehicle is en route to the loading dock.

- Where required, entry into the facility loading dock should be controlled and observed by CCTV. All personnel who may receive or make shipments should be aware of the procedures employed by the facility to ensure the security of the loading dock area and all shipping and receiving procedures. Package inspection/screening requirements should also be reviewed.

5.3.4 Vehicle Access Control and Parking

Vehicle controls can most appropriately be applied at those transit facilities that are not typically open to the public-such as administrative offices, maintenance facilities, operation control centers-as a way to deter unauthorized or illegal access. Some of the methods listed here may also be applied around suburban transit stations or other public facilities with significant available parking and a steady flow of pick-up/drop-off traffic.

Agencies should follow these vehicle control and parking guidelines for vehicle inspection, facility parking/traffic control, adjacent parking, parking registration/vehicle ID, unauthorized vehicles, vehicle access points, high-speed vehicle approaches, drive-up/drop-off locations, and electronic vehicle access control.

Design considerations - refer to Section 6.2.1 Security strategies - refer to Vehicle Access subsection in Section 6.3 |

5.3.4.1 Vehicle Inspection

Vehicle inspections ensure that incendiary devices, explosives, or other items that pose a threat to security are not present.

- Inspections must be limited and no more intrusive than necessary to protect against the danger of sabotage or similar acts of destruction or violence, based on the existing threat level. The inspection should, however, be reasonably effective.

- Inspection techniques include, but are not limited to, magnetometers, physical examinations of the person or objects visually or through the use of trained animals, electronic devices, x-radiography or a combination of these methods. Used of trained animals may be limited due to availability and safety in systems where a third rail is present.

- If evidence of criminal activity or contraband is discovered during security inspections, it should be treated as a criminal act and the appropriate procedures for such an act should be followed.

- All vehicles entering or leaving the facility should be subject to search by security personnel. Signs should be posted to advise persons of this requirement.

5.3.4.2 Facility Parking/Traffic Control

- Where required, access to non-public parking should be limited to transit agency vehicles, personnel, contractors, and authorized visitors. This can be accomplished by use of a trained guard force, parking lot barriers such as barrier arms, or at a minimum, designation and identification of authorized parking spaces.

- Visitor parking should be clearly marked and should be as close as possible to the visitor reception area of the facility. Parking should not be permitted close to or against perimeter barriers. Handicapped parking may be allowed within the established buffer zone if the vehicle and operator are identified to the staff responsible for parking control.

- Whenever possible, parking areas for all transit and staff vehicles should be located inside the perimeter of protected areas.

- Where possible, parking areas for general vehicles should be located outside a facility's buffer zone. Parking should not be allowed within 100 feet (30.5 meters) of the building exterior, when possible. Parking areas may be fenced and should be well lighted in accordance with the existing illuminance specification.

- Parking within the facility should be restricted only to those areas indicated in a facility physical security plan.

- Parking lot activity should be monitored either visually or by CCTV.

- Parking regulations should be strictly enforced.

- Emergency communication speakers should be installed in the parking area in order to broadcast emergency procedures and/or instructions.

- Vehicle entry and exit routes should be clearly marked.

- A facility should have formal procedures for controlling vehicle access and parking.

5.3.4.3 Adjacent Parking

- Where possible and where prudent, areas adjacent to transit facilities may be controlled to reduce the potential for vehicle-based threats against transit agency facilities and employees.

5.3.4.4 Parking Registration / Vehicular Identification Systems

- Facilities implementing a vehicular identification system should establish procedures for identifying vehicles in accordance with established credentialing procedures.

- A visual vehicle identification sticker/badge system can be used independently or to supplement the electronic entry control system.

5.3.4.5 Towing of Unauthorized Vehicles

- Procedures for towing unauthorized vehicles at facilities should be established. Reasonable and prudent steps should be made to locate and identify the operator of unidentified vehicles.

- If the operator cannot be located within a reasonable time and the vehicle cannot be verified as harmless to the facility, the vehicle should be removed by the safest, most expeditious, and prudent means. Local towing companies may be utilized for this service.