Go to report table of contents

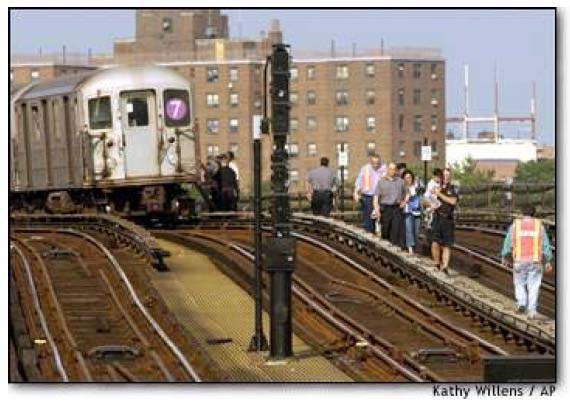

Figure G-1. Subway evacuation during the 2003 blackout

Appendix G. Lessons Learned from Transit Communications Emergencies

Transit agencies can use communications experiences from real-world emergencies not only to respond better during times of crisis, but also to improve communication during day-to-day operations.

Two recent emergencies that transit agencies can learn from include the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C., and the August 14, 2003 blackout that occurred across the Northeastern United States.

This appendix describes how transit agencies responded to the:

- September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks

- August 14, 2003 blackout

Summary

Communications lessons learned from these two emergencies include:

- A single point of failure can disrupt the entire communications system.

- It is important for an agency to maintain backup power for all segments of its communications network.

- The need for interoperable communications among agencies increases during emergency situations.

- It is important for an agency to have multiple forms of communications technology at its disposal.

- The problems experienced with communications technology in one emergency may be very different in the next emergency. An agency needs to be prepared for a changing set of circumstances.

- The public can now obtain information from multiple sources, including e-mail alerts, Internet updates, cell phones, and radio technologies.

- A communications system will experience an unusually high demand during an emergency, exactly when it may be the most vulnerable. Agencies should take advantage of federally sponsored emergency communications programs to ensure they are able to maintain communications during such times.

September 11, 2001 Terrorist Attacks

- New York City

- Washington, DC

New York City

In New York City, vital communications links were damaged or overwhelmed by demand. The damage included the loss of electrical power, and the destruction of landline communications facilities and radio towers.

Backup Power

New York City Transit's (NYC Transit) response to the Con Edison Washington Heights blackout in the summer of 1999 had confirmed the value of emergency power generators. Since that time the agency had been purchasing a fleet of trailer-mounted diesel generators.

On September 11, these trailers were dispatched to Lower Manhattan and were used to provide power to pump out the underground subway stations and tunnels, as well as the telephone and utility vaults located near the World Trade Center. The Mayor's Office of Emergency Management (OEM), the New York Police Department (NYPD), and the New York Fire Department (FDNY) also relied on these emergency generators to maintain emergency communications services in Lower Manhattan.

Redundancy

Both NYC Transit and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (Port Authority) maintain separate landline telecommunications systems independent of the commercial phone company. On September 11, the Port Authority's system was destroyed, but NYC Transit's system remained functional and was used by the emergency response agencies to maintain communications.

Both NYC Transit and NJ Transit had "mobile" communication centers (40-foot transit buses equipped with satellite communication and computer technology), which were used as command posts for communications and decision-making. NYC Transit also monitored some of its subway stations from its mobile command post using CCTV. Both agencies provided and maintained vital communications links and services for transit as well as federal, state and city emergency command posts through their mobile communications units.

Communication with the Public

Aware of the need to keep the public informed of their transportation options, NYC Transit took the key step of informing both the media and the riding public about constant service changes the first two weeks after September 11.

During the first three days of the disaster, NYC Transit made over 40 changes to subway service; these changes were announced using service notices (Take Ones) and maps handed out by transit employees. Information was also disseminated on the transit agencies' respective web sites. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) reported 10 million web hits on its web site on one day after the September 11 attack, five times the normal volume.

Other Findings

Several agencies found that certain communications alternatives proved successful in the emergency response efforts for, particularly for internal information dissemination. Agencies reported that interactive pagers, such as the Blackberry pager, were extremely useful on September 11, when other forms of communication were unavailable.

The NYPD maintains the largest public safety mobile radio system in North America and it remained operational at all times. Nonetheless, it also experienced problems: available channels were extremely crowded, and there were interoperability problems when responders using incompatible radio equipment (operated in different bands) were unable to talk to one another.

At the FCC's Public Safety National Coordination Committee's General Meeting in November of 2001, the NYPD highlighted the fact that because they operate a substantial portion of their own communications infrastructure, they were able to keep E-911 call-taking and dispatching operating. This was an important point to make, because some public safety organizations have been urged to use commercial services to provide their public safety communications. The NYPD felt that September 11 highlighted the critical need for exclusive public safety communications systems that ensure secure quality transmission and reception.

The FDNY learned hard lessons about its audio communications abilities. Their mobile radio system temporarily lost the ability to transmit after the first tower collapsed. The incompatibility of their mobile communications system with that of the Police Department also prevented the agencies from communicating directly with each other. The critical issue of interoperability is being addressed by changing over from VHF to UHF, which will give the FDNY the ability to communicate within its own agency as well as with the NYPD and the Emergency Medical Services (EMS).

Washington, D.C.

In Washington, D.C., The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) operates Metrorail rapid transit lines and an extensive Metrobus transit service throughout the region. Metrorail and Metrobus maintain separate command centers, but in major emergencies, their functions are consolidated into a single, central command post. On September 11, Metrobus drivers could not be notified of all service changes at once since the radio system required that dispatchers call drivers individually.

Telephones were the main communications technology used on September 11 at Washington, D.C.'s command center. But when circuits jammed on the East Coast, the center switched to mobile devices and global satellite phones, instant messaging, and e-mail.

Command Center

Even before the attack on the Pentagon, WMATA had set up a special command center following the attacks in New York, which monitored operations and remained open for much of the day. The command kept in close contact with the FBI, fire departments, and other law enforcement agencies in the region. The center heightened system surveillance, alerted tactical police, and sent sniffing dogs to find suspected explosives at stations, noting that WMATA received tips of suspicious packages seen in the system.

Emergency Preparedness

WMATA considers itself to be well prepared to deal with emergencies because of training, drills, and spot checks. Emergency preparedness is an important priority at WMATA because Washington is a prime target for terrorist attacks; the agency assumes that additional attacks on the nation's capital are inevitable.

August 14, 2003 Blackout

The August 2003 blackout caused a large portion of the Northeast and Great Lakes region to lose electrical power just as the evening rush hour was commencing (see Figure G-1). A major obstacle facing transit agencies and other government agencies in dealing with the blackout was the loss of communications. Activities such as vehicle evacuations had to be conducted without effective central coordination from the OCC. A NYC Transit dispatcher was quoted as saying in the transit agency's newsletter, "For transportation, I think the blackout was worse than 9/11. And the reason is, no communication." Communication problems included technology failures, as well challenges with disseminating timely information within an agency, among agencies, and to the general public.

Technology Failures

When designing a communications system to function during an emergency, it is crucial that the system be designed to eliminate single points of failure. Several transit agencies lost their radio communications because of a failure in at least one portion of its network. One agency's backup power did not work, resulting in inoperable radio communications; another agency had its antennas fail due to a loss of power. Repeaters failed to work on emergency backup or ceased operations after the battery power ran out. The NYPD's radio system experienced brief outages during the initial hours of the event.

|

Figure G-1. Subway evacuation during the 2003 blackout |

It is important for a transit agency to understand which segments of its communications system depend on external systems and resources.

New York City's 911 emergency telephone system experienced failures because of the loss of power at the phone company's switching stations. It also experienced the highest demand in its history on August 14, and the phone company's queuing capacity was not sufficient to handle the call volume. NYC Transit's paratransit operations were able to maintain power throughout the blackout, but some of its contracted vendors lost power. As a result, the vendors lost communications with the central operations center and had to resort to manually picking up trip manifests from the central offices.

Most agencies were not prepared for such a long loss of power as the one that occurred during the August blackout. Most backup batteries installed on the towers and repeaters were designed to work for approximately four to six hours. Cell phones and Nextel direct connect radios eventually lost power after several hours when their batteries died. Communications capabilities degraded as their reserve power supplies were exhausted.

Many problems faced during the blackout were not the same as past events. The Port Authority had implemented redundant means of communications, relying especially on text messaging technology, including e-mails and Blackberries, which are personal assistants with access to e-mail, phone, and web information. After its Operations Center lost power, the Port Authority's Internet system went down and text messaging was severely constrained.

Technology Changes

There were several examples of technological changes implemented as a result of lessons learned from September 11 that helped agencies better respond to the blackout. For example, NJ Transit established a dedicated 1-800 telephone number for key staff to be able to communicate the details of the agency's response plan.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|