Washington Post

November 14, 2002

Pg. 28

Inspectors' List Of Sites Ready

'Road Map' Includes More Than 1,000 Locations in Iraq

By Colum Lynch, Washington Post Staff Writer

UNITED NATIONS, Nov. 13 -- With Iraq's announcement today that it will accept tough, new United Nations inspection terms, a team of disarmament experts will likely arrive in Baghdad on Monday to restart their surveillance cameras, install their communications equipment and begin the most intrusive weapons inspection operation in modern history.

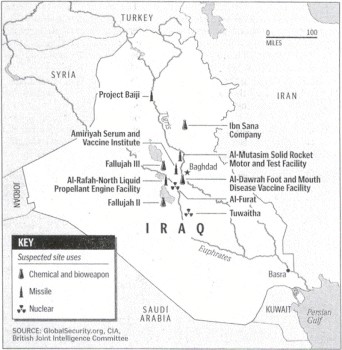

Armed with tips and evidence amassed by Iraqi defectors, former U.N. arms experts and U.S. and British intelligence agencies over the past decade, the U.N. inspection team has created a road map of more than 1,000 sites that inspectors will potentially visit in their search of Iraq's suspected chemical, biological and nuclear weapons arsenals.

Over the next two months, U.N. inspectors will be zeroing in on a priority list of more than 100 sites, including an upgraded missile launch facility at Al-Rafah, a former nuclear power plant at Al-Furat and a chlorine production facility in the town of Fallujah outside Baghdad that once produced precursors for Iraq's nerve and blister agents, according to U.S. and U.N. sources. Inspectors are also expected to visit at least one of eight presidential compounds to test whether Iraq is willing to provide full compliance, officials said.

U.S. and British intelligence agencies maintain that these and other sites damaged by U.S. warplanes or destroyed by U.N. weapons inspectors have been rebuilt and expanded since the inspectors left Iraq in December 1998, on the eve of a U.S.-British bombing campaign.

"We have a plan of action which we cannot obviously lay out in detail," Mohamed El Baradei, the director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, said in an interview. "But we will have to go and visit some of the facilities which have been relevant in the past". . . and conduct "no notice inspections" at previously unknown sites. "We would not want to work in an expected fashion; we will have to do some surprise visits to facilities that we might not be expected to visit."

El Baradei, an Egyptian arms expert who will head the United Nations' efforts to uncover Iraq's nuclear weapons program, said that these former sites represent only a piece of the broader picture of Iraq's weapons program. El Baradei and his counterpart, Hans Blix, the head of the U.N. Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission, which is responsible for ridding Iraq of chemical and biological weapons and long-range missiles, said the U.N. inspectors will set up an elaborate system of soil, water and air sampling equipment to detect any traces of chemicals or radioactive materials.

Inspectors will also appeal to U.N. member states to turn over intelligence on Iraq's efforts to purchase weapons-related equipment, and question hundreds of Iraqi scientists involved in Baghdad's previous weapons efforts to see whether they can provide credible evidence they have not been "moonlighting" in prohibited programs, El Baradei said.

But El Baradei and other senior U.N. officials say the key to identifying a secret weapons program is securing unimpeded access to any site in the country. "If there is a piece of equipment, it will have to be installed; and if it has been installed and is being used, we will have a chance to bump into it," said Jacques Baute, the head of the IAEA's Iraq action team.

Under the terms of a 1991 cease-fire agreement ending the Persian Gulf War, Iraq is obliged to allow U.N. inspectors to eliminate its chemical, biological and nuclear weapons program and any missile with a range of more than 90 miles. The former U.N. inspections agency, UNSCOM, destroyed more Iraqi weapons than the U.S.-led coalition forces in 1991 before it left Iraq in 1998, following confrontations over access to sites.

But Iraq retained massive stores of growth media and chemical precursors that could have been turned to chemical and biological weapons programs. U.S. officials suspect that Iraq has also developed longer range missiles and other delivery systems capable of threatening U.S. interests.

Blix and El Baradei will travel to Iraq on Monday with a team of nearly 30 logistical and technical specialists to set up communications and check on the status of an elaborate remote monitoring system that kept tabs on pieces of Iraqi equipment that could easily be converted from civilian to military uses. A team of about a dozen weapons inspectors are scheduled to arrive Nov. 25 to begin conducting spot inspections. A full team of 85 to 100 inspectors should be working in Iraq by the end of December.

Reports issued last month by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency and Britain's Joint Intelligence Committee charged that Iraq has been engaged in an ambitious program over the past four years to rebuild facilities either torn down by previous U.N. inspectors or destroyed by U.S. and British warplanes.

The reports include the names of more than a dozen locations suspected of participating in banned weapons programs. One of them is the Al Mamoun Solid Rocket Motor Production Plant, where Iraq previously produced motors for the Badr-2000 solid propellant missile, which is capable of traveling 430 to 620 miles.

Although U.S. warplanes and U.N. inspectors have destroyed several structures at the site, the Iraqis have begun to rebuild them. "The Iraqis have rebuilt two structures used to mix solid propellant for the Badr-2000," according the CIA report. "The only logical explanation for the size and configuration of these mixing buildings is that Iraq intends to develop longer-range, prohibited missiles."

U.N. officials say that much of the information published in the report -- including an account of weapons-related equipment and materials sought from overseas suppliers by Iraq -- provides a helpful guide to future weapons inspections. But they also struck a note of caution, pointing out that Iraq will have plenty of time to sanitize those sites. "Where sites have been indicated publicly, it is not likely that they will contain anything proscribed when inspectors arrive," Blix told a team of recruits in Vienna last month.

El Baradei said that while his inspectors could easily detect whether Iraq has reconstituted an industrial-scale nuclear weapons program, it will be much harder to uncover evidence of Iraq's efforts to obtain weapons-grade nuclear fuel from a foreign supplier. He said that although he will begin inspections in "a couple of weeks' time," it could take as long as three months before the entire U.N. monitoring system will be up and running. "We need to take our time," El Baradei said.

El Baradei and Blix have repeatedly pleaded with Washington and London to provide them with fresh intelligence they have collected on Iraqi efforts to procure key ingredients that can be used for either conventional or nuclear weapons programs.

©2002 Washington Post